"The Soup" by Pablo Picasso, 1903, oil on canvas (Courtesy of The Phillips Collection/Art Gallery of Ontario, © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

As the 50th anniversary of his death approaches, Pablo Picasso and his work loom large, and even casual art lovers can freely associate him with cubism, blue and rose periods, and "Guernica" (1937) — his reaction to the Spanish Civil War. Many know Picasso was staunchly atheist, but it will surprise many to know he drew extensively upon Catholic imagery throughout his career.

"Picasso was marvelously informed about how the Roman Catholic representation of various religious figures matters to the faithful," Mary Ann Caws, a distinguished professor emerita at City University of New York and author of the 2005 book Pablo Picasso, told NCR. "He painted what he could of the religious imagery, even as he himself was not always worshipful."

Some of the earliest religious works appear in "Picasso: Painting the Blue Period" (through June 12) at Washington's Phillips Collection. In several, Picasso humanized downtrodden women by painting them in a manner that was traditionally reserved for the Madonna, according to Susan Behrends Frank, Phillips Collection curator. "These very small, close-up images, in which he monumentalized figures from the street," she said.

In "Melancholy Woman" (1902, Detroit Institute of Arts), a woman dressed entirely in blue sits with her legs crossed and back against a wall. Some light pours in from a window, vaguely suggesting a halo around the woman, who was incarcerated in the Parisian women's prison Saint-Lazare. Picasso visited on several occasions as a 19-year-old in 1901, upon his friend Dr. Louis Jullien's invitation. Those interned were unaware the visitor was an artist, and Picasso was probably dressed as a doctor making rounds, Behrends Frank said. So ethical concerns clearly abounded in a scenario where the incarcerated remained in the dark.

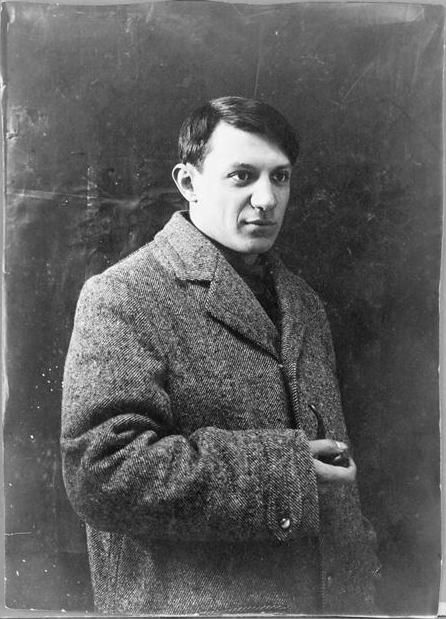

Portrait photograph of Pablo Picasso, 1908 (Wikimedia Commons/Anonymous)

But it is also noteworthy that Picasso observed otherwise-invisible women and decided, upon returning to his home studio, to beatify them visually, drawing upon a Spanish Catholic aesthetic vocabulary. This picture must have been important to Picasso, who included it in a 1932 exhibit — essentially his first major retrospective.

"She's very hieratic in a way that a medieval Madonna would be," Behrends Frank said. "Very straight back. Looking away from you. She's clearly engaged in her own thoughts."

Elsewhere in the exhibit, Picasso drew on his Catholic upbringing in "Evocation (The Burial of Casagemas)" (1901, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), which memorializes his friend, who took his own life. That led, in part, to his adopting the somber palette of the blue period.

Mourners surround Casagemas' body in the foreground as a mausoleum appears to the right. Above, in heaven, a nude woman embraces a man (Casagemas?) on a horse, flanked by children at play and other nude women, who "are like brothel prostitutes," Behrends Frank said. "It's very much a blasphemous work."

Although Picasso did not go to church, he was "imbued with this religion from the time he was a child growing up, and so recognizing that this is a way people understand and think about the world or their relationship to the world, he can poke the bear, so to speak," she said.

Writing in the 2007 book A Life of Picasso, the late art historian John Richardson called Picasso "the anticlerical scion of a clerical family," who "was all the more eager to expose the Catholic nobility as the enemy." But Picasso proved "surprisingly conventional" when it came to his son Paolo's education at three Catholic schools, for which his former wife Olga lobbied. However, "His father's attitude toward the church would apparently rub off on the boy," who was thrice expelled, Richardson added.

Advertisement

"I hate the Catholic Church," Picasso said on another occasion, as recorded in An Interview with Pablo Picasso (2014) by Neil Cox, "though my wife Jacqueline [Roque] says I am more Catholic than the pope!"

The story of Picasso's connection to Catholicism is more complicated, however, in Jane Daggett Dillenberger and John Handley's marvelous 2014 book The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso. The two detail Picasso's Catholic schooling, and early works like "First Communion" (1896) and "Science and Charity" (1897), both at Museu Picasso, Barcelona. Throughout his life, Picasso used the crucifixion as an important symbol of both death and renewal, and nowhere was he more pioneering and innovative than in melding Spanish bullfighting culture and the crucifixion.

In a 1959 drawing which was part of a book Pablo Picasso: Toros y Toreros, Picasso drew a man posed cruciform in the foreground holding his cape (muleta), which doubles as a loincloth, to steer a bull away from a fallen horse and man. "The Christ-matador figure has drawn the bull away from the picador, who lies half beneath his fallen horse, supporting himself upon his elbows and looking up toward Christ," Dillenberger and Handley write. The latter evokes depictions of Saul's conversion, where the future St. Paul can be found beneath his fallen horse, they add, and Picasso deliberately blurred the lines between bull, Christ, horse and man.

"Between these two beasts, one the aggressor and the other the victim, lies the crumpled form of the fallen man," the authors write.

“Crouching Beggarwoman” by Pablo Picasso, 1902, oil on canvas (Courtesy of The Phillips Collection/Art Gallery of Ontario, © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

Picasso, like other members of the Catalan avant-garde, was a "cultural or 'lapsed' Catholic, who used the precepts of the faith to criticize the ills of modern capitalist culture," said Kenneth Brummel, curator of 20th-century art at the Joslyn Museum of Art in Omaha. Brummel, who co-curated the exhibit with Behrends Frank in his previous role at Art Gallery of Ontario, called Picasso's 1896 annunciation (made when he was 15-years-old, and now at Museu Picasso, Barcelona) a "key work" in the show.

Of the 1897 "Science and Charity," Brummel noted that Picasso compared a nun's charity to a doctor's medicine. "Picasso situates the Catholic faith in a fully secular context," he said. And Picasso continued to secularize Catholicism, even in "Guernica," Brummel said. "Is not the wailing woman at the left of that painting a secularized Madonna holding the dead body of Christ?"

"Crouching Beggarwoman" (1902, Art Gallery of Ontario), in the show, depicts suffering and resignation that recalls depictions of Our Lady of Sorrows that the young Picasso would have seen in Spain, and the exhibit juxtaposes the picture with Luis de Morales' "Our Lady of Sorrows" (1560-70, Prado, Madrid).

"We believe Picasso transforms the impoverished figure in 'Crouching Beggarwoman' into a secularized, iconic representation of the Virgin Mary to elicit feelings of empathy from his largely Catholic, Catalan audience," Brummel said. "Isolating her, enlarging her, and situating her in an indistinct environment, Picasso treats her as a devotional figure, almost asking his bourgeois audience to revere this poor woman as if she were a saint depicted on a panel in an altarpiece."

And in "The Soup" (1903; Art Gallery of Ontario), also in the show, Picasso depicts a woman performing an act of charity by offering a bowl of soup to a child. Picasso deliberately staged the scene in a nondescript location, "outside of time and place," Brummel said.

"Monumentalizing these figures while also emphasizing their poverty, Picasso implies that virtuous behavior is not to be found in civic buildings or in representations of religious personages, but in common places such as the street or the slum, where the poor struggle daily to survive."