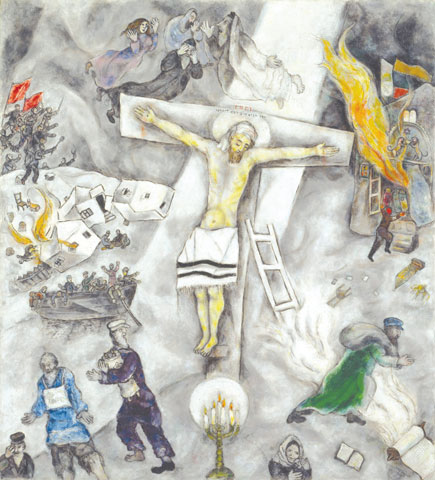

"White Crucifixion" by Marc Chagall (Courtesy of Art Institute of Chicago)

When the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, advertised its exhibit "The Age of Picasso and Matisse: Modern Masters from the Art Institute of Chicago" on its website, it didn't mention that Marc Chagall's 1938 painting "White Crucifixion" was part of the trove migrating south during Chicago's seven-month renovation of its modern wing.

Writing last February in The Dallas Morning News, Michael Granberry suggested that the painting deserves its own study. "It's telling that Chagall, a Russian-born Jewish artist, painted it in the same year as Kristallnacht, the 'Night of Broken Glass' that offered a grim foreshadowing of the Holocaust," he wrote.

But both Granberry and the museum may have buried the lede, or eliminated it altogether. With the Chagall painting and 100 other works from the Art Institute's modern European painting and sculpture section now back home in Chicago, it's important to note that the work, which depicts a decidedly Jewish Jesus on the cross, is also reportedly Pope Francis' favorite painting.

To be fair, site-wide searches of the websites of the archdioceses of Boston, Chicago, Washington, Galveston-Houston, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia and San Francisco yield no mention of the painting. And in several conversations with visitors during the member preview of the restored section at the Art Institute, not a single person knew about the papal preference for the Chagall painting.

The Art Institute's renovation, according to a press release, responds to "wear and tear" on its third-floor galleries from the millions of visitors who have come since the modern wing opened in 2009. The newly opened galleries feature repainted and refinished walls, floors, podiums and cases, as well as improvements to the "energy-efficient light harvesting system for the galleries" that will "ensure consistent light levels across all rooms."

Under newly consistent light and amid the slick renovation, Chagall's Jesus wears a sort of turban on his head, and instead of a loincloth he dons a Jewish prayer shawl, or a tallit. Surrounding the central crucifixion scene, a synagogue burns to the right, rabbis fly in the air above (where one might expect angels), and a pogrom ensues to the left. Above Jesus' head, on the titulus, Chagall writes the Latin acronym "INRI" and, in jumbled Hebrew and Aramaic, "Jesus the Nazarene, king of the Jews."

Whether Chagall, who grew up with extensive Jewish instruction despite the multitude of errors in many of his Hebrew inscriptions, knew that the way he spelled Jesus' name in Hebrew also doubled as the rabbinic acronym "May his name and his memory be wiped out" is debatable. But it's certainly clear that the work "owns" Jesus as a Jew. And as the Art Institute website observes, it aims to "dramatically call attention to the persecution and suffering of the Jews in 1930s Germany."

Gretchen Buggeln, professor of Christianity and the arts at Valparaiso University's Christ College in Indiana, admitted she didn't know that Chagall's "White Crucifixion" was a papal favorite. But she wasn't surprised, given the pope's view of Jesus as a human and divine "exemplar of compassion."

"In this painting, Jesus is at the center of some of the most horrific suffering Chagall can imagine," she said. "And he is not just among the suffering, but truly identified as one of the suffering."

Chagall, who has always been a "very popular painter," has a way of appealing across religious grounds, according to Margaret Olin, who holds appointments at Yale University's Divinity School as well as its departments of religious studies, Jewish studies, and art history. But "White Crucifixion" is quite controversial, she noted.

"The appropriation of Jesus as a Jew is an implicit criticism of Catholicism for viewing the Jew as other, for not recognizing one's own suffering in that of the Jews. Taking over Christian iconography is a critical move," she said. "For the pope, the Jewish Christ may be enough to make the point about the failure of the church, and this might well speak to him."

Servite Fr. John Pawlikowski, director of the Catholic-Jewish studies program at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, agreed.

"The painting comes out of the movement, particularly among Yiddish-speaking, nonreligious Jews, to see Jesus as sharing in the sufferings of Jews at the hands of Christians. However, few, if any, Christians are really aware of this movement," he said.

Most Christians will interpret the painting as displaying a direct link between Jesus' suffering and Jewish persecution during the Holocaust, according to Pawlikowski. But that can lead Christians to identify "themselves as victims, especially of the Nazis, rather than as a community of faith that contributed to Jewish suffering over the centuries," he said. "The painting, as moving as it is, can send an inaccurate message."

Pawlikowski suspects the pope's adoration of the work has something to do with "his longstanding commitment to Catholic-Jewish relations in Argentina," he said. "He showed particular sensitivity to Jewish suffering at the time of the [1994] bombing of the Jewish center in Buenos Aires."

[Menachem Wecker, who is based in Chicago, is the former education reporter at U.S. News & World Report. His book, Consider No Evil: Two Faith Traditions and the Problem of Academic Freedom in Religious Higher Education, coauthored with Brandon Withrow, will be published this summer by Cascade Books.]