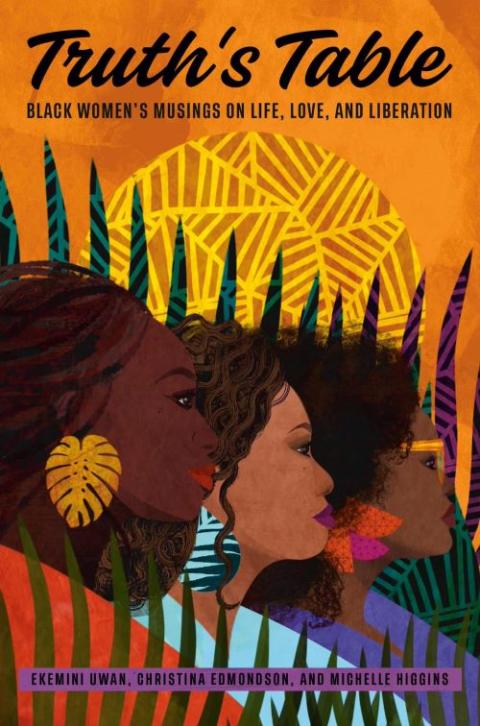

Christina Edmondson, from left, Michelle Higgins and Ekemini Uwan, say their work is designed expressly for Black women but they welcome others into their audience, to what they call their "standing-room section." (Courtesy photo)

The three Black women — a public theologian, a senior pastor, an educator and psychologist — first got to know each other through a group chat.

After having wide-ranging discussion on religion, race and gender, they met at a conference, where they were encouraged to start a joint podcast. Now, their book, Truth's Table: Black Women's Musings on Life, Love, and Liberation, was released April 26.

Ekemini Uwan, Michelle Higgins and Christina Edmondson have said their work — in audio and in print — is designed expressly for Black women but they welcome others into their audience, to what they call their "standing-room section."

"Truth’s Table: Black Women’s Musings on Life, Love, and Liberation" was released April 26. (Courtesy image)

"We see y'all, but the sisters are at the table," said Uwan, 39, who attends an African Methodist Episcopal church in the Washington metropolitan area and is the Black Christian Experience Resource Center's 2022 inaugural theologian-in-residence.

Edmondson added that, though their focus is on Black Christian women, they also read and learn from the stories of people who do not share their gender or culture.

"It's hard for us to see ourselves, actually, culturally, unless we engage cross-culturally," said Edmondson, 42, a scholar-in-residence of a multiracial Presbyterian Church in America congregation in Nashville, Tennessee. "So I really think there is a benefit and a gift to people who don't identify as Black Christian women to listen respectfully to these stories and narratives in the same way that I pick up books by authors who are outside of my own demographics all the time."

The trio announced in December that Higgins, a justice activist who leads a United Church of Christ congregation, was leaving the podcast "to continue her movement and ministry work in St. Louis." Uwan and Edmondson, while continuing with the sixth season of the "Truth's Table" podcast, are also co-hosting a second podcast, "Get in the Word With Truth's Table," in which they are reading the entire Bible during 2022.

The two, who are promoting their book while Higgins is on medical leave, spoke to Religion News Service about the challenges and joys for both single and married Black women, countering white supremacy and their hopes for the future of Black American Christians.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RNS: Your book is dedicated, in part, to "Black girls who considered leaving the church when their imago Dei wasn't enough." Why did you choose to make that declaration as you started the book?

Uwan: It was important for us to be able to rightly identify the ways Black women have often felt like they just simply were not enough, or maybe too much, in various church contexts. And so we wanted to be clear about that and name that, from the outset, to let Black women know we see you, we know you, and we love you.

Edmondson: Even before we get to the part about those who consider leaving the church, we pay homage to grandmothers and aunties and mothers and spiritual mothers. I think we see ourselves as standing in a very, very long tradition. We are not a new phenomenon. We also wanted to reinforce that idea that we see ourselves as an echo.

Ekemini, you wrote about colorism and describe it as "the offspring of white supremacy" and say in the more than 15 years you have been a Christian, you have not heard it addressed in a sermon in a Black church. Can you explain briefly what colorism is and what you'd like to hear preached about it?

Uwan: It's a dynamic that occurs intraracially, although it can happen externally too, whereby dark-skinned people are discriminated against and where light-skinned people are preferenced over against dark-skinned people. And that impacts income level, employment status, our interaction with the criminal justice system, marriageability options and dating. It also impacts those various facets of our lives for dark-skinned people. What I would love to hear from the pulpit is just even a recognition that this is a very real, lived reality for many people within the church context. It would be great to hear some sort of an acknowledgment of that and also a refutation of colorism and a condemnation of it.

Christina Edmondson, left, is a scholar-in-residence of a multiracial Presbyterian Church in America congregation in Nashville, Tennessee. Ekemini Uwan attends an African Methodist Episcopal church in the Washington metropolitan area and is the Christina Edmondson, left, is a scholar-in-residence of a multiracial Presbyterian Church in America congregation in Nashville, Tennessee. Ekemini Uwan attends an African Methodist Episcopal church in the Washington metropolitan area and is the Black Christian Experience Resource Center's 2022 inaugural theologian-in-residence. (Courtesy photo)

Christina, you recall being "angry Black womaned," by people who think you fit a certain stereotype.

Edmonton: I made up that word, angry-Black-womaned, but I thought that Black women would resonate with that lived experience. I've certainly been angry-Black-womaned. And I think the main reason is because if I'm speaking to something in my work around anti-racism, people get in their feelings very quickly on that topic. I think it makes it very easy for them to go to the trope of the angry Black woman versus listening to the facts, the data, the history, and so certainly in my teaching capacity that has happened. That's happened in really flippant ways in social media. In the book, I give an example of stating something fairly matter-of-factly and someone being like, well, you know, "Christina's just angry." And I was like, "I'm actually feeling pretty good today." We shouldn't fall for the trope.

Ekemini, you speak of having a righteous anger about the demographics in Black churches, saying they should "connect the dots between our congregations teeming with single Black women and the two single Black men in our pews." What specific ways do you think the church should address or assist single Black women?

Uwan: One of the interventions that I propose is much more of a Pan-African response. I do believe the Black church has got to come together collectively. I'm talking about the African church, traditional Black church, Caribbean church. We all got to come together and have a family meeting and really put our minds together about how we can begin to support the single Black women in our congregation. And what would it look like for the Black women who desire to be married to a Black man, what would it look like for those congregations to cross-pollinate?

Christina, you describe your own marriage of 20-plus years as "an act of resistance" and you say that "Black Christian marriages are a necessary countercultural act of grace." Why do you think they hold that kind of power?

Edmonton: There are so many ways in which the Black family represents the reunification of the emancipation promise. The first thing many emancipated, formerly enslaved Africans did in the United States in the late 1860s, is they worked hard and they scraped together pennies so they could put out articles to say: I'm looking for my mother. I'm looking for my husband. I'm looking for my daughter. Black people have been trying to get back to their families since the Africans from Angola were brought to Virginia.

Seeing Black men and Black women just being together is enlivening for people, because I think it is satiating a core trauma. And so to stand in that, to choose each other over and over again, is a resistance to white supremacy.

Advertisement

Toward the end of the book, your co-author Michelle Higgins writes, "The future of Blackness is the full right to be called family in the household of God." Is there something each of you look for most in the future after all that you've described as an often-difficult past and present for many African American Christians?

Edmonton: The family reunion, the image of that Black American tradition all over the States, but especially in the South, of this return to our matching T-shirts, and we are united around these tables again with Big Momma and cousins and everybody's got a place. Everybody's got a chair. And even our conflict and tension can't make it into the door. The family has been reunited.

Are you saying that is in heaven or before heaven?

Edmonton: There are appetizers of the buffet that come into now. I think God's goodness is not just reserved for the sweet by and by.

Ekemini, what are you looking for most in the future?

Uwan: This Pan-African reunification of seeing and being reconnected with loved ones, distant relatives, ancestors that were snatched during the trans-Atlantic slave trade and seeing Africans and African Americans and Caribbean siblings being reunited and experiencing restoration together, the reclamation of their ethnic identity. Knowing I am Nigerian American, but I won't be Nigerian in glory. I will be Ibibio, my ethnic identity. I paint that picture at the end of the book, about this glorious reunification I believe we will see in glory. And I do believe it breaks forth into now. But I do believe that we will see that and we will experience that in glory.