In this June 27, 1985, file photo, Nina Simone performs at Avery Fisher Hall in New York. (AP Photo/Rene Perez, File)

"The name of this tune is 'Mississippi Goddam,' " Nina Simone announces without missing a beat in the bouncy, cabaret-style cadence she beats out on the piano keys. The mostly white audience at Carnegie Hall leaks nervous laughter in response.

But Simone wasn't joking. She'd brought her rage at the lynching of Emmett Till, the murder of Medgar Evers and the bombing of Birmingham's 16th Street Baptist Church to Carnegie Hall's stage that March night in 1964 — the same rage that had enabled her to pen that iconic protest song in less than an hour.

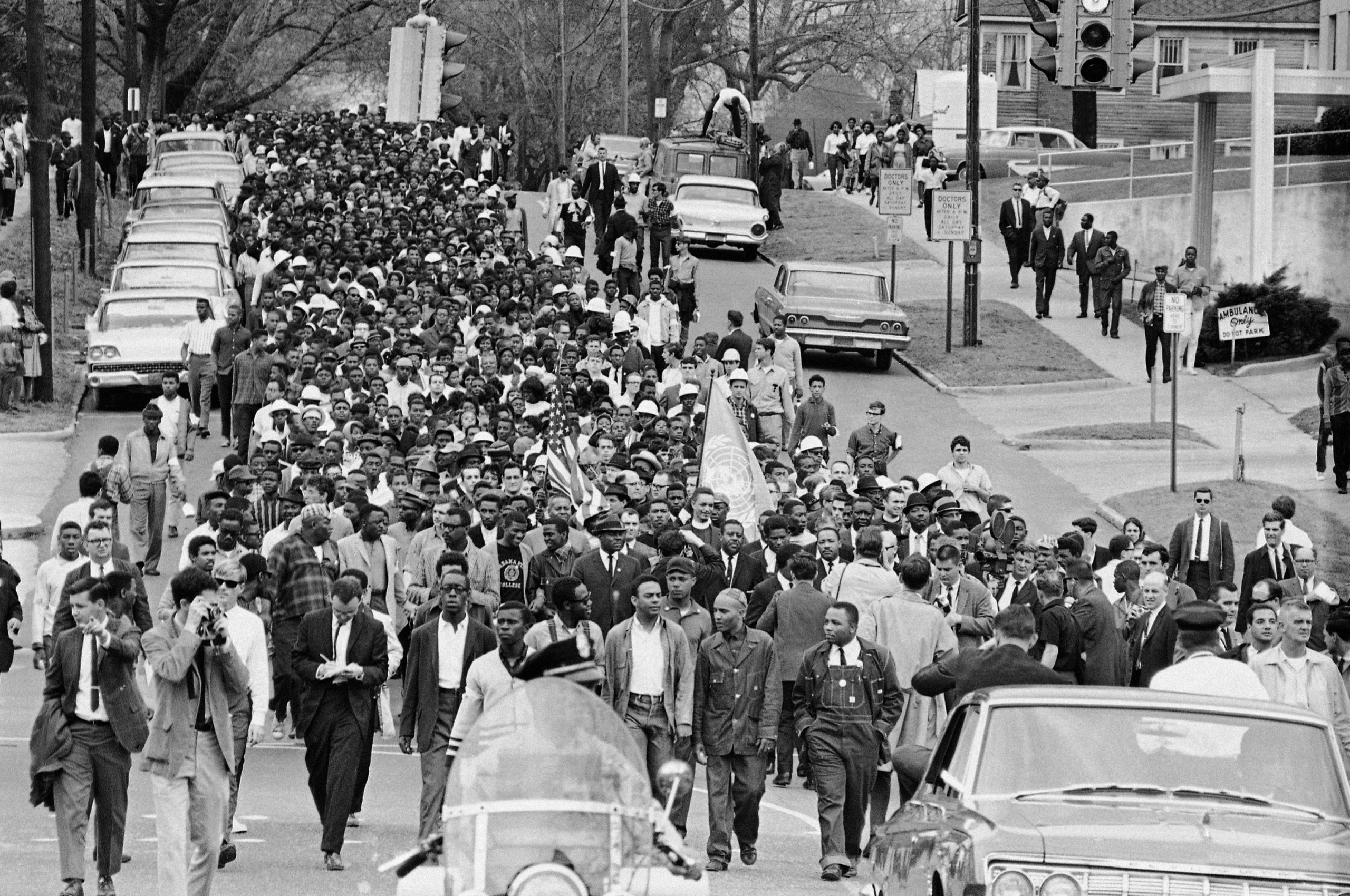

"Mississippi Goddam" would be banned on Southern radio stations, become an anthem of the civil rights movement and the following year be played on the famous march from Selma led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Simone is one of many Black artists whose life and work illuminate the prophetic tradition that connects Black art and the struggle for Black liberation. From Harriet Tubman singing "Go Down Moses" to announce her presence to Black captives in the Southern work camps, to Marvin Gaye's timeless anti-war anthem "What's Goin On?", to the co-founding of the Black Lives Matter movement, the largest social movement of our generation, by performance artist and abolitionist Patrisse Cullors, Black artists have long shouldered the prophetic burden to tell the truth about a society that refuses to confess its sins against Black bodies.

Advertisement

Art is essential to Black liberation movements.

An artist myself, I've repeatedly returned to the work of Black artists to bolster my own sense of vocation in a world that often pressures me with a false choice between being an entertainer or being an activist. A pantheon that includes Simone, Amiri Baraka, Toni Cade Bambara, Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, Bob Marley, Ava DuVernay and others reminds me that no such choice must be made.

These artists did not and are not offering only, as theologian N.T. Wright often says, "the pretty bit around the edge" of Black liberation: We are essential freedom workers.

Art is essential to Black liberation movements because half the battle against oppression is a battle to disrupt a supremacist common sense that pervades the world, especially those nations that were (or are) perpetrators or victims of European colonialism. No matter how many revolutions are won in the world — by arms or by nonviolent struggle — oppressive institutions will continue to reproduce themselves if there is no revolution of values.

This is why Occupy Wall Street co-founder Micah White writes in his 2016 book The End of Protest, "In our global struggle to liberate humanity, the most significant battles will be fought on the spiritual level — inside our heads, within our imagination and deep in our collective unconscious."

Art communicates on that spiritual level, and the powers know it.

FILE – In this March 17, 1965, file photo, demonstrators walk to the courthouse behind the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Montgomery, Ala. The march was to protest treatment of demonstrators by police during an attempted march. (AP Photo/File)

Authority tacitly admits art's revolutionary power when it bans songs like "Mississippi Goddam" or tries to cut books such as Toni Morrison's Beloved from school curricula. Art can also encourage the other side: The Ku Klux Klan never burned a cross until the Klansmen in D.W. Griffith's film "Birth of a Nation" did so.

Given the power of art to influence social action, artists have a tremendous role in shaping the culture of freedom movements. In his book about the 1963 campaign to desegregate Birmingham, Why We Can't Wait, King wrote that freedom songs were "the soul" of the civil rights movement.

"I have stood in a meeting with hundreds of youngsters and joined in while they sang ‘Ain't Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me 'Round'. It is not just a song; it is a resolve," King writes. "A few minutes later, I have seen those same youngsters refuse to turn around from the onrush of a police dog, refuse to turn around before a pugnacious Bull Connor in command of men armed with power hoses. These songs bind us together, give us courage together, help us to march together."

King's words have reassured me, but the more I engage the work of liberation as an artist, I'm convinced art is more than just useful for sustaining activism. Art is the exhale of a mind breaking free of colonialism's cognitive chains.

When I opened Black Skin, White Masks, by the mid-20th-century revolutionary and writer Frantz Fanon, I was taken aback that he chose to start the book with poetry, rather than the elegant linear prose I expected. The lauded philosopher and psychiatrist instead began a work analyzing the psychological aspects of racism with lyrical stanzas — stanzas whose form immediately challenged the epistemological biases we've inherited from the European enlightenment that elevate prose over verse.

In art, we recover the wisdom of ancestors who knew truth is embodied, it is danced, it is sung, painted or embroidered, felt and even traversed in geographical space.

As we talk about radical solutions to systemic oppression — abolishing police and prisons — we are forced to build the same skills useful to the artist: imagination, collaboration and improvisation. We are seeking to create a beautiful new world out of the mess colonialism continues to make. We are breaking with the rigid, oppressive structures of colonialism, as poets and songwriters break the usual rules of grammar.

Given the power of art to influence social action, artists have a tremendous role in shaping the culture of freedom movements.

Remaking the world without systemic racism will take our best creative selves. The artist must stand among the politicians, organizers and clergy who have always been in the vanguard of freedom movements.

We need artists who care about social justice today to know that they stand in a deep tradition of prophetic truth-tellers who have helped us understand the world better. We need to know the brilliance of poet Aime Cesaire's Discourse on Colonialism and its contribution to Black anti-fascist thought. We should talk more about the social analysis within Langston Hughes' anti-capitalist poetry, including his bold address to the Second International Writers Conference where he calls out American fascism.

The artist's role in society isn't to shut up and sing, or dance or dribble. We are creative leaders, and to paraphrase King, human salvation is in the hands of the creative minority who remains maladjusted to injustice.