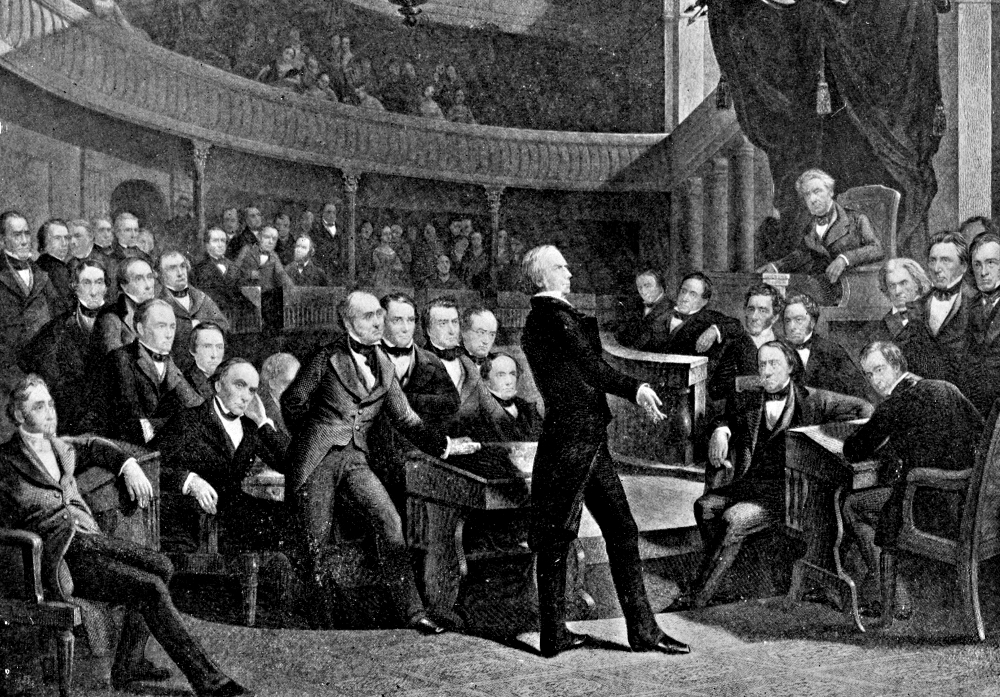

A 1900 illustration depicts the U.S. Senate in 1850, as Sen. Henry Clay delivers a speech. Seated in the second row behind him is Daniel Webster, and on the far right is John Calhoun. (Wikimedia Commons)

Editor's note: Don't miss out on Michael Sean Winters' latest! Sign up to receive emails, and we will notify you when he publishes new Distinctly Catholic columns.

The collapse of the effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act was good for those millions of people who would have lost their health insurance under any of the various Republican proposals. As I wrote last week, however, the entire debate represented a step back for democracy. The Senate's bizarre procedures, bringing forth bills the contents of which were unknown, the use of the reconciliation process to enact changes that have nothing to do with budgetary concerns that the reconciliation process was designed to handle, and the sheer moral callousness of 49 of the country's senators — all bode ill for the values that Catholic social doctrine celebrates: solidarity, human dignity, a commitment to democratic norms and processes, and responsible government.

The debate also provided a key piece of evidence in an emerging theory about how the Trump presidency will play out. Increasingly, the lack of tools essential to governance — an awareness of policy options and familiarity with the consequences of those options, a willingness to listen and compromise, the extension of loyalty to political allies, a disciplined communications strategy — creates nothing but chaos in the White House.

In politics, chaos creates a power vacuum. And, in Washington, there is no shortage of people willing to fill a power vacuum.

Ever since World War II, the presidency has become the preeminently powerful branch of government. If you knew nothing about the United States, and merely read a copy of the Constitution, you would think Congress wielded the most power. The Constitution vests Congress with the power of the purse, but in recent decades, the budgeting process begins with a budget proposed by the president. Congress writes the laws, but presidents now realize that implementation of those laws requires interpretation, and in the last two presidencies, signing statements by the president could largely shape whatever legislation Congress had passed.

And the most awesome power a government possesses, the power to declare war, since the advent of the atomic bomb, presidents have wielded that power on their own, sometimes asking Congress for a vote of approval, but never for a declaration of war.

A relief on the Daniel Webster Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Wikimedia Commons/Daderot)

These postwar years have been the exception: Through most of the country's history, it was Congress that was the most powerful branch of government. Here is an easy parlor game to demonstrate the point: Tonight, at dinner, ask everyone at the table to name the presidents between Jackson and Lincoln. Maybe someone can do it. There was a time when I could name all the presidents in sequence but there was also a time when, following their promotional advertising, I could list the ingredients in a Big Mac.

Franklin Pierce and Millard Fillmore are not memorable, but everyone at least vaguely recalls Sens. Daniel Webster, Henry Clay and John Calhoun, known as "the Great Triumvirate." There is a wonderful monument to Webster just up the street from St. Matthew's Cathedral in Washington. I have not found Fillmore's monument.

Interestingly, the period in which the three senators dominated the politics of the nation was also a time of partisan shifting. The Federalist Party had collapsed entirely with the end of the War of 1812. The Era of Good Feelings that marked the presidency of James Monroe did not witness a need for a second political party. But as the Democrats radicalized under Andrew Jackson, the Whigs emerged as an alternative party.

Advertisement

Daniel Walker Howe's The Political Culture of the American Whigs is the definitive history of these years in which national unity was repeatedly threatened as the still-young Republic grappled with the sectional rivalries that arose from the fact of slavery. The various compromises of the antebellum era staved off the prospect of war for a time, but the underlying problem did not admit of compromise.

When the war came, it was more horrible because of that delay, as advances in military technology far outstripped advances in medical knowledge. But no one can tell if the war had come sooner it would have turned out as it did. The Union might have crumbled.

The Whigs of yesteryear, however, have little in common with today's Republican Party. Their nationalism was acute, but it was directed at preserving national unity, not dividing the country. "Reminded of our fathers, we should remember that we are brethren," wrote Rufus Choate, the Massachusetts congressman and lawyer. President Donald Trump is not known for his looking back to history for any reason.

In his remarkable speech to his colleagues upon his dramatic return to the Senate last week, John McCain stood for the kind of statesmanship we associate with the Great Triumvirate, but he stood almost alone. His call for a return to regular order and renewed bipartisanship was not heeded.

You do not need to know much about Webster to know that Sen. Mitch McConnell is no Webster. Speaker of the House Paul Ryan's commitment to abstract libertarian ideology, so pronounced in the health care debate, disqualifies him from any comparison with the Whigs, who specifically, and repeatedly, distanced themselves from the sweeping ideological liberations celebrated by the Jacksonians. The Whigs, incidentally, saw Jackson as an American Bonaparte, but it is Trump who surrounds himself with generals.

The vacuum of power in the presidency, in short, may not give rise to a reassertion of congressional dominance because the leadership of the Congress is so enfeebled by its own pathologies or at least its own lack of leadership. Then what?

It is given to none of us to predict the future, but it is becoming increasingly difficult not to wonder if America has begun its final decline. Just as the Spain of Philip II and the France of Louis XIV and the British Empire of Victoria each declined in due course, will the age of Donald Trump mark the real beginning of the end of the American empire?

The exposure of political and cultural weaknesses that we are no longer able to overcome are not the result of Trump alone: Questions about whether the Constitution can withstand the political forces unleashed by the hyper-partisanship that led McConnell to refuse a hearing to Judge Merrick Garland existed before Trump. The president is a symptom, one that degrades our entire democracy to be sure, but he is not a cause, and that is what we must reckon with.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., on Capitol Hill in Washington July 25 (CNS/Reuters/Aaron P. Bernstein)

In the face of these grim realities, what are we as Catholics to think? As ever, there is wisdom to be found from the psalmist: "I will praise the Lord while I live; I will sing praises to my God while I have my being. Do not trust in princes, in mortal man, in whom there is no salvation."

That text has been around longer than the U.S. Senate. It was prayed at the White House before it was the White House.

It is a time to seek refreshment from the wellsprings of our culture, not from its incoming tides. It is time to recognize the limits of politics as well as the necessity of politics. It is a time to brace ourselves for the havoc that these miserable men, and they are still mostly men, will cause to our country and to our planet.

It is time, then, to refresh and to resist.

[Michael Sean Winters is NCR Washington columnist and a visiting fellow at Catholic University's Institute for Policy Research and Catholic Studies.]