Each year, the Hispanic community of Mount Angel Seminary in St. Benedict, Oregon, hosts a large festival in honor of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Several hundred people come for the celebration that includes Mass, Mexican food, dance and music. (Courtesy of Mount Angel Abbey)

Mount Angel Seminary supporters argue that the West Coast's largest center for priest education and formation is a sitting duck for uninformed reproaches, a strawman for stereotyping.

They note concern that the school will be unfairly rolled up into blanket criticisms of secluded campuses and priest-on-pedestal formation programs set out in a recent Boston College report and a detailed March 2018 critique by the Association of U.S. Catholic Priests.

While the nearly 130-year-old seminary does rest on a somewhat remote 46-acre hilltop an hour from Portland, Oregon, it is far from a hotbed of clericalism and preconciliar sympathies, say students, faculty, administrators and others familiar with the school.

Open its doors, they say, and one finds:

- A culturally and ethnically diverse student body that reflects the changing demographics of the church: Nearly half are Latino, and there is a strong representation of Pacific Rim nationalities, plus African-American and Native American students.

- A solid, fully accredited and cohesive curriculum that embraces Vatican II.

- A cohesion of the seminary and the Mount Angel Benedictine community that provides an atmosphere of prayer, stability, hospitality and humility.

The Benedictines founded the seminary in 1889 and today own and operate it, along with an active and expanding retreat center. Mount Angel Benedictines also earn high marks for their brewery and taproom.

Interviewees repeatedly underscored the role played by the monastery community, lauding the 55 monks' leavening presence and role-modeling of healthy, pastoral and celibate lives.

The monastery's abbot doubles as the seminary chancellor, currently Abbot Jeremy Driscoll. A diocesan priest serves as president-rector, currently Msgr. Joseph Betschart of the Portland Archdiocese.

Familiar with Mount Angel for more than three decades in his former roles as the Seattle Archdiocese's vicar general and as bishop of Helena, Montana, Bishop George Thomas of Las Vegas has appreciated what he sees as the Benedictine-inspired "emphasis on learning how to pray."

"It is great that the guys have the example of the monastic life," Thomas recently told NCR. "They have the opportunity to take part in the day-to-day rhythm of the monks, but at the same time they are being well-prepared to learn how to pray in the context of parish and pastoral life. I have seen this year after year."

Second-year theology student Peter Laughlin said, "Learning how to sort of 'pray always without ceasing' has been very impactful." Rather than "compartmentalize" prayer, the Portland Archdiocese seminarian says he has a growing awareness of God's constant presence, of seeing "God in moments of rest and in work."

A first-year theology student, Ian Gaston of the Diocese of Orange, California, said the Benedictines "provide a lot of stability, and they also provide a very particular attention to having the theology department very liturgy-oriented. They have some monks as teachers, and again, just the stability and the environment kind of ground us all."

Franciscan Sr. Katarina Schuth, professor emerita at the St. Paul Seminary School of Divinity in St. Paul, Minnesota, says she is "very familiar with Mount Angel and visited there about a half dozen times."

"Since Mount Angel is based at a Benedictine monastery with a long history of well-educated monks, I think they have maintained a wholesome philosophy, appropriate to changes in the church since Vatican II and have been quite successful in preparing men pastorally, even in their somewhat remote setting," Schuth, a nationally recognized expert on priestly formation, said in an email.

'The goal is to learn how to be authentic'

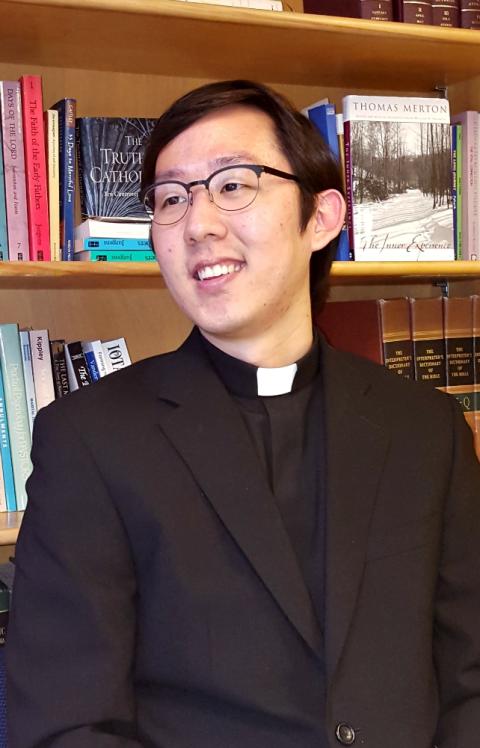

Theology student Val Park, 31, told NCR that the diversity of the seminary student body "was a dimension I did not see" prior to enrolling at Mount Angel. Immediate past chair of Mount Angel's Korean community, Park has appreciated the school's encouragement of interethnic and intercultural exchange.

Val Park (NCR photo/Dan Morris-Young)

A Seattle Archdiocese seminarian, Park appreciates "being surrounded by such a diversity — different cultures, guys from different parts of the country, different expectations."

He and others point to seminarians' wide-ranging work histories that include pruning apple trees, filling prescriptions, teaching school, and working in real estate.

For his part, Park spent considerable time helping his father operate a hotel after graduating from Western Washington University with a history degree.

Park's countless hours behind the front desk, he said with a smile, had the pastoral side benefit of helping him learn "how to deal with things that were not always pleasant for me."

At the seminary, Park said, "The goal is to learn how to be authentic, to be yourself as you learn how to get along with your brothers, and you allow them to challenge you."

The student population also reflects the spectrum of thought and conviction on the panorama of church issues. Importantly, several repeated, the differences are fodder for conversation and exchange, not divisiveness or polarization.

Twenty-two-year Mount Angel faculty member Deacon Owen Cummings says faculty also come down on various sides of what can be hot-button topics. If the differences did not exist, he said, "it would be surprising and unfortunate."

"But," Cummings said, "there is no polarization. There is polarization in other places, but we have a very centrist way of looking at things that cross all the disciplines of theology."

"And I think that is attractive to a bishop because you don't want guys who are either spaced out on the right or the left because they will just create huge problems for them later on. I think that creates a level of trust in the totality of what we are doing," said Cummings, Regents' Chair of Theology and director of the Doctor of Ministry program.

Mount Angel's 123 seminarians represent 19 dioceses and five religious communities; 47 non-seminarians are also enrolled, including seven women.

Several interviewees lauded campus comradery, often enhanced via cultural events sponsored by one of the ethnic cohorts.

Advertisement

Park called attention to Monday dinners during which upcoming community events are made known. "There are announcements and announcements," he said. "On any given weekend, there are two or three events organized by seminarians themselves. It's one sign of how vibrant this community is."

Anthony Hoangphan, a theology student from the Portland Archdiocese, is no stranger to those events as a onetime chair of the Vietnamese seminary contingent. He applauded "the variety of people with a variety of experiences coming here and sharing."

"Without realizing it perhaps," said Driscoll, "the friendship and brotherhood among the seminarians from the various ethnic Catholic cultures that makes up the life of the churches in the Western states is reflected right here, and the model of a beautifully diversified and united church is lived out in our daily existence together."

Preparing to serve the Hispanic faithful

While seminarian ages range from 18 to 60, the majority are 24 to 35. Also inching toward a majority is the number of candidates of Hispanic/Latino heritage.

A former chair of the Mount Angel Hispanic community, Abundio Lopez draws particular attention to the group's efforts "to work with others and just to be friendly, warming and inviting so that they can learn and understand what the Hispanic culture is, and for them to eventually go back to their dioceses and to be able to share a little bit."

"It is important to understand what it is that Hispanic families are all about and their culture," added Lopez, a student from the Diocese of Tucson, Arizona.

Considerable attention is paid to developing familiarity with Spanish, headed by Anna Lesiuk, associate professor of Spanish and Latin.

Anna Lesiuk (NCR photo/Dan Morris-Young)

Latino seminarians themselves come from varied backgrounds, she pointed out, and include what she describes as "heritage speakers" and "native speakers."

The seminary "has a large population of heritage speakers, which means somebody born here or who arrived as a child," she explained. "They can easily converse in Spanish, which for parish life can be enough, but they have not received formal studies. They struggle with written Spanish. They cannot really write it well."

Native speakers, she said, tend "to have grown up in Mexico and came to the U.S. after high school." They "do not need much help with written Spanish, but they are still interested in learning more about the language and about Spanish-language literature."

Seminarians with no facility with Spanish start from the beginning, where Lesiuk insists on as much verbalization as possible.

As students advance, they are exposed to "more and more pastoral vocabulary," sometimes nicknamed "church Spanish," she said.

Weekly Spanish-language Masses are celebrated at Mount Angel, and there is significant student-to-student tutoring and support.

Educating seminarians on the lingual, historical and cultural variations of Latino life has been "received very positively" by bishops, Lesiuk said, "because they are well-aware of the situation, the increasing population of Spanish-speaking faithful in our church communities."

Msgr. Robert Siler of the Diocese of Yakima, Washington, agrees. "We are very pleased with the work Mount Angel does in forming men for priesthood, and both men and women for pastoral service in the church," said Siler, chancellor and moderator of the curia for the Yakima Diocese, where more than 70 percent of Catholics are Hispanic.

A 2001 Mount Angel graduate, Siler feels he "was well-prepared pastorally for priesthood." His formation and education were augmented by summer Spanish-language immersion in Mexico and "migrant ministry" in the diocese.

Embracing Communion ecclesiology

Cummings and Driscoll are primary creators of a curriculum approach they have named Communion ecclesiology.

Communion ecclesiology is an "integrated curriculum" focused on "relating parts of the eucharistic rite to specific themes in the theological academy with a view toward celebrating Eucharist with deepened understanding and deriving from it pastoral energy, inspiration and direction," according to Driscoll.

The Vietnamese community of Mount Angel Seminary annually hosts a celebration of the Lunar New Year. The day brings several hundred visitors to the seminary and includes Mass, traditional Vietnamese New Year food, dance and music. (Courtesy of Mount Angel Abbey)

Communion ecclesiology, he said, "indicates that our sense and understanding of church are rooted in the Eucharist and in the communion effected by God there. This is communion in the life of the Trinity, communion with one another, communion as pastoral goal, communion with all people, communion as a pastoral style."

"This overriding vision shows up in virtually all the courses in theology and integrates them," said Driscoll, who with Cummings and others has been "crafting and refining" the practice for 25 years.

While somewhat nebulous to neophytes, seasoned students clearly understand and embrace Communion ecclesiology.

Betschart sees Communion ecclesiology as "really unique and really a great gift and a hallmark that we have."

"The sense of our whole program is focused on the Eucharist. We seek to ... allow the Eucharist to be the source and summit of our life. We draw our strength from it, our service from it, and we turn back to it.

"We seek to form men who are men of the Eucharist, men of Communion, priests who live in that communion with God, with themselves, with their community, with one another," added Betschart.

Overall, the seminary program of priestly preparation is bracketed within what are called the four dimensions of formation — spiritual, academic, pastoral and human. The school has a director for each of the four: Fr. William Dillard, spiritual; Shawn Keough, intellectual; Missionary of the Holy Spirit Fr. Peter Arteaga, pastoral; and Fr. Steve Clovis, human.

Each seminarian meets regularly with both a spiritual director and a director for human formation. There are currently nine formators on the human formation team, including monks, diocesan priests, and religious.

The nine-member team gathers for hourlong discussions three times weekly. The meetings often include the seminary president-rector as well as Clovis and Benedictine Sr. Judith Bloxham, associate director of human formation.

Over an academic year, the group will have discussed in detail each seminarian at least twice, according to Fr. Terrence Tompkins, Mount Angel vice rector whose duties also include teaching religious studies and being a formation director for 16 second-year theology students.

Tompkins shared an outline of evaluation points. It lists seven major areas from leadership and physical health to celibacy and personal accountability. More than 40 additional assessment items fall under those.

"There are naturally times when we might find ourselves spending more time discussing some seminarians than others if a given seminarian seems challenged at a certain point in time," said Tompkins who has been at Mount Angel 11 years.

Aided by his formator, a seminarian prepares a self-evaluation highlighting growth and achievement as well as areas needing attention. The statement is reviewed with the formation team.

At this time of year, formators start pulling together a wide spectrum of material for annual assessments of each candidate including faculty comments, grade transcripts, field education supervisors' input and the seminarian's self-evaluation.

"Vocation directors, frequently accompanied by the bishops, come to the seminary during spring semester for an in-depth presentation of the formal evaluation ... with the seminarian present," said Tompkins. "The seminarian will have already seen the written evaluation so there are no curveballs or surprises for him."

"The seminarian then has approximately one week to submit an accountability statement which demonstrates that he heard especially well the recommendations in the report for the sake of his future growth and has formulated what could be called a strategic action plan in terms of how to address those recommendations going forward," explained Tompkins.

[Dan Morris-Young is NCR's West Coast correspondent. His email is dmyoung@ncronline.org.]