Gregoria Caceres prays next to a picture of Pope Francis placed outside the Virgin of Caacupé chapel in Buenos Aires, Argentina, April 21, 2025, after the death of Pope Francis was announced by the Vatican. The pope, then Jorge Mario Bergoglio, was named a Buenos Aires bishop in 1992. (OSV News/Reuters/Matias Baglietto)

For a whole generation of Argentinian Catholics, Jorge Mario Bergoglio has been the major inspiration for their pastoral work over the past three decades. Although many of these priests and lay activists now feel fatherless, most think the paths opened by Pope Francis cannot be closed, despite potential changes introduced by a new pope.

The history of key ecclesial movements in Argentina is related to Bergoglio, who became an auxiliary bishop in Buenos Aires in 1992 and the archbishop of Argentina's capital in 1998. Many people who worked side by side with him until he left the city and was elected pope in 2013 affirm that his major goal was always to increase the Catholic presence among the poor.

"In 15 years as the archbishop, he created only one new parish that was not in a popular neighborhood or in a villa (a slum)," said Fr. Guillermo Pablo Torre, a cura villero (slum priest) known as Padre Willy. "He'd always send more priests to hospitals, prisons and slums, the most abandoned places in society."

The curas villeros movement was founded in the 1960s by a group of priests excited about the fast changes in the Latin American church after the Second Vatican Council. The Movimiento de Sacerdotes para el Tercer Mundo (Movement of Priests for the Third World) was led by Fr. Carlos Mugica, who dedicated several years of work to Villa 31 de Retiro in Buenos Aires. In 1974, he was shot dead by members of a right-wing paramilitary group called the Triple A (Anti-Communist Alliance of Argentina).

'We lost a father, but we have many brothers and sisters who were encouraged by that same father and will now sustain us.'

—Romina Roda

As an archbishop, however, Bergoglio transformed the curas villeros' ministry into an official vicariate and greatly incentivized it.

"He would constantly visit Villa 31 de Retiro, where I worked for 22 years, during protests, festivities and celebrations. He had a very close contact with the people. He would have a drink of [yerba] maté with them, visit their homes, have dinner with them," Torre said.

Juan Romero has lived in Villa 31 since his childhood and would often play soccer with Mugica. He remembers seeing Bergoglio in the area since the 1990s.

"We staged large protests against a governmental attempt to relocate the villa's residents in order to build a highway," he said. "Some of the slum priests went on a hunger strike. Bergoglio would constantly come to accompany the priests."

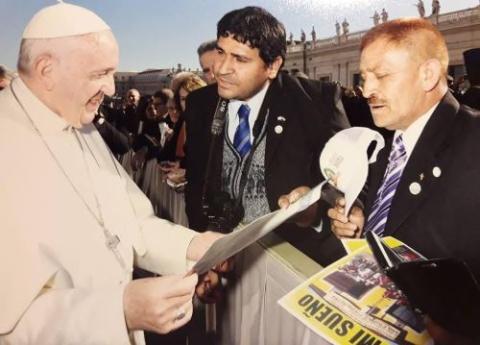

Cesar Sanabria and Juan Romero, both Villa 31 residents, talk with Pope Francis at the Vatican in 2018. Romero remembers seeing the future pope, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, in the Buenos Aires slum area in the 1990s. (Courtesy of Juan Romero)

Then-councilor Humberto Bonanata would lament, in a 2020 article, that the slum still exists only because Bergoglio called President Carlos Menem and begged him to maintain the villa in the same place it was created in the 1930s.

"I still remember that he always had his cassock full of mud. The villa was very muddy those days," Romero said.

For people like Romero, it was "like Bergoglio was under the wings of Fr. Mugica," giving inestimable support to their community.

In another Buenos Aires slum, Villa 21-24 de Barracas, a major ecclesial movement was founded in 2008, directly influenced by Bergoglio.

"[Slum priest] Fr. Pepe di Paola invited him to the villa during Holy Week and he decided to begin with a washing of the feet ceremony," Romina Roda, a national coordinator of the Hogares de Cristo (Christ's Homes) movement, told NCR.

That gesture had profound significance: It invited the church to put the poor at the very center of all its concerns, in a way that they should be seen as integral subjects and not as problems to be solved.

"He would repeat to us that we should 'welcome life as it comes and accompany it hand-to-hand,' " Torre recalled.

Pope Francis greets a group of Argentine visitors holding images of Fr. Carlos Mugica, an Argentine priest and activist, after the pope's general audience at the Vatican May 8, 2024. Mugica, who ministered in Villa 31 de Retiro in Buenos Aires, was shot dead by members of a right-wing paramilitary group in 1974. (CNS/Vatican Media)

Hogares de Cristo gradually became a federation of several neighborhood centers that work to give "integral answers to situations of social vulnerability and the consumption of psychoactive substances, by putting the people and their qualities first."

"Addiction is only the tip of the iceberg. We know that people are complex, as are the reasons for their problems as well," Roda said.

Hogares de Cristo's mission is to embrace the individuals living in vulnerable conditions, providing the necessary social and interpersonal support to help them rebuild their lives.

"Women have always had a central role in that process. Bergoglio gave back to us our voices and our right to take part in the decisions," Roda said. Even now, lay people and women still have a central role in the Federation of Hogares de Cristo.

Roda lives in the northern province of Tucuman, where 12 Hogares de Cristo centers operate. Although the situation in the province is very different from that of Buenos Aires' villas, the movement's model seems to function successfully there. She has been working with the Hogares for 10 years.

"Bergoglio knew from close the situation of poverty and exclusion that exists in Latin America. That experience gave him an extraordinary sensibility to understand what was happening in other parts of the world as well," she told NCR.

Advertisement

Such a closeness with the poor was a two-way street. Romero recalls the day Broglio was announced as the newly elected pope.

"People celebrated his election in Villa 31 like they would celebrate a goal of Argentina against Brazil in a soccer match. It was a tremendous party," he said.

While Argentinians in general reject the idea of religious powers meddling in politics, Bergoglio's moral vision would continue to be central for many social segments, including in politics.

Ultra libertarian economist Javier Milei, who once called Francis a "filthy leftist," won Argentina's 2023 presidential election. He was opposed by many social activists and political leaders who evoked the pope's teachings concerning the need to build just societies, in which the poor receive the necessary help to make a living.

Not coincidentally, the most active ecclesial groups opposing Milei's anti popular measures — especially when it comes to the insufficient adjustment of pensions — have been the curas villeros and the Curas en la opción por los pobres (Priests in the Option for the Poor), a movement that directly descends from Mugica's Movement of Priests for the Third World.

The group had prepared an open letter to the pontiff in which they asked him not to visit Argentina. Since the beginning of his tenure in the Vatican, he experienced continuous pressure to travel to his motherland. His disagreements with Milei — which the politician took to a personal level, insulting Francis for years in interviews and social media posts — were apparently behind his avoidance to do so over the past couple of years.

The Priests in the Option for the Poor feared that Milei's recent efforts to bring Francis to Argentina could succeed, so they made a long list of reasons — mainly focusing on the leader's neoliberal policies — why Francis should not visit. It was published posthumously.

In a message concerning the pope's death, the group said that Francis always wanted to show, "from the choice of his name to his gestures, with his words and attitudes, a poor Church, without luxury, simple from its language to its attitudes."

Argentine Archbishop Jorge Ignacio García Cuerva of Buenos Aires, right, reacts as he concelebrates Mass at the Basilica of San Jose de Flores April 21, 2025, following the death of Pope Francis. The pope, formerly Argentine Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, died April 21 at age 88. (OSV News/Reuters/Agustin Marcarian)

According to Fr. Francisco "Paco" Olvera, one of the group's leaders, Francis' death does not mean the end of his dreams.

"Never! We follow a crucified [man] who God took down from the cross. The oppressors will not have the last word, and in the meantime, [we must] stand by the oppressed with or without the pope of the people," he said.

That seems to be the spirit of many people who were directly inspired by Francis in Argentina. Slum priest Pablo Viola, who lives in Cordoba, said that the pontiff was not an isolated individual with good ideas, "but the expression of a church that went through a rich process over the past decades, and he knew how to interpret such a process as a pope."

"I believe God will not abandon us — and that dream will keep leading the church to walk side by side with the poor," Viola said.

Padre Willy and Roda also think that the changes Francis introduced will continue even after his death.

"Of course, we're now shocked by our loss," Roda said. "We lost a father, but we have many brothers and sisters who were encouraged by that same father and will now sustain us."