Sr. Helen Kearney, center, president of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Brentwood, New York, and St. Joseph Sr. Mary Doyle, right, participate in the Global Climate Strike Sept. 20, 2019, in New York City. The youth-led march and rally was one of many demonstrations held around the world urging government and business leaders to take immediate action to combat climate change. (CNS/Gregory A. Shemitz)

When most 19th century apostolic congregations of Catholic sisters were founded, responding to and being directed by bishops was the name of the game. But after the Second Vatican Council that mindset began to change as other criteria such as reading the "signs of the times" became important in discerning new missionary imperatives. Today, Catholic sisters all over the world are prioritizing care for creation as integral to their work.

In the years immediately following Vatican II, conciliar documents, Pope Paul VI's Populorum Progressio and the bishops' 1971 synod on justice in the world generated an enthusiastic response from many sisters to step up and respond to the cry of the poor, and not long afterward to the cry of the earth, too.

From the 1970s onward, Catholic sisters were influenced not only by bishops' environmental statements and scientific publications about environmental degradation, but also by the works of theologians such as Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Columban Fr. Sean McDonagh and Passionist Fr. Thomas Berry, cosmologist Brian Swimme and more recent eco-feminist publications such as St. Joseph Sr. Elizabeth Johnson's Women, Earth, and Creator Spirit and Ask the Beasts: Darwin and the God of Love, Brazilian theologian and Augustinian Sr. Ivone Gebara's Longing for Running Water: Ecofeminism and Liberation, the publications of Franciscan Sr. Ilia Delio and more.

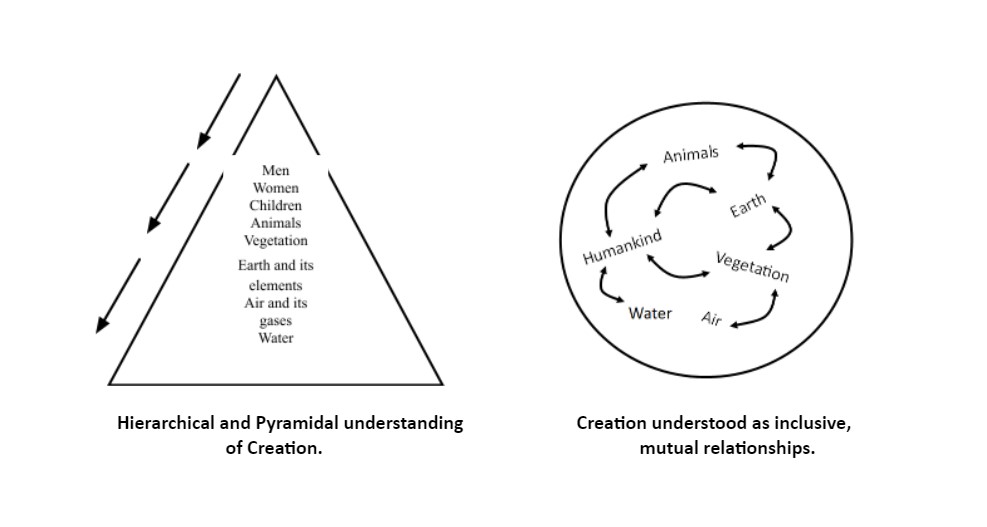

Such eco-feminist publications encourage movement beyond earlier hierarchical, dualistic theologies that position man at the apex of creation with all other creatures deemed subordinate. A pyramidal understanding of creation has meant a real pecking order in the life of planet Earth — the higher up the pyramid one is positioned, the more they can dominate and exploit those relegated to lower positions. This dualistic theology did not see care for creation as a missionary imperative — not when there were millions of souls to be saved for eternal life. But fruitful collaboration between science and theology no longer supports such understandings of the ecosystems within creation.

Diagrams compares a hierarchical and pyramidal understanding of creation, and creation understood as inclusive, mutual relationships. (Diagrams prepared by Carmel Cole of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions, and Ruth Mather)

Long aware of the damage patriarchal and hierarchical ideologies cause, Catholic sisters understand that theologies grounded in those ideologies should be replaced by theologies that encourage mutuality, inclusivity and interdependence. We know all creation shares a common origin — stardust. We know that we need Mother Earth more than she needs us. So instead of hierarchical theologies, eco-theologians invite us to reclaim trinitarian theologies that emphasize the Trinity as a relationship of mutuality, interdependence and equality — values that need to inform humankind's relationship with the rest of creation.

Furthermore, Catholic sisters are exploring experientially what responding to the cry of an exploited earth might entail. For example, in 1980 the Dominican Sisters of Caldwell, New Jersey, established Genesis Farm which sought to model holistic ways whereby humankind could relate to their environments. The struggles of other valiant women such as Kenyan Wangarĩ Maathai (1940–2011) and Indian Vandana Shiva resonated with the struggles of Catholic sisters concerned about environmental degradation. Sisters found themselves becoming part of a worldwide movement of women united in their care for creation.

For some Catholic sisters, mission on behalf of the environment has been truly costly. Notre Dame de Namur Sr. Dorothy Stang was murdered in 2005 in Brazil because of her opposition to logging companies involved in the deforestation of that country. The Adorers of the Blood of Christ sisters who protested against a company trying to build a 200-mile natural gas pipeline to carry shale gas from fields in northeastern Pennsylvania to distant ports were harassed because of their opposition.

Advertisement

Filipina sisters are likewise active in resisting the environmental degradation caused by mining and oil companies in their country, often in lands which have been home to Indigenous peoples for centuries. One such congregation, the Missionary Benedictines, now see their action and solidarity with Indigenous peoples as key in their ministry. And recently, it has been heartening to learn of some congregations donating in extraordinarily generous ways to organizations committed to environmental care.

These are just a few examples of the prophetic actions of Catholic sisters committing themselves to care for creation, no matter the cost.

It is not difficult to demonstrate that sisters are often ahead of the institutional church in matters environmental. In 2012, in my congregation, when we were rewriting our constitutions, canon lawyers advised us against too much emphasis on new cosmologies and eco-theologies. These might be considered "trendy," rather than integral to Catholicism, they warned. Three years later in 2015, Pope Francis' encyclical, "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home" speedily subverted such institutional opposition. Catholic sisters greeted the encyclical with great enthusiasm.

Mercy Sister Aine O'Connor, Marianne Comfort, justice coordinator for the Mercy Sisters, and Mercy Sister Rita Parks, all from Silver Spring, Maryland, hold aloft signs Sept. 20, 2019, in front of St. Patrick's Church in Washington as they prepare to join the climate change march. The Washington rally was one of several taking place across the country and in England and Australia. (CNS/Carol Zimmermann)

Growing numbers of sisters, along with millions of others, are aware of what is happening in our world today. Sisters who are directly involved in ministries with the economically and politically disenfranchised poor can easily see how environmental degradation more severely impacts oppressed communities. Climate change means more droughts, more cyclones, more forest fires, more exploitation of natural resources leading to deforestation, more invasions of land of Indigenous peoples as multinational companies engage in mining and oil drilling activities that demonstrate zero respect for Mother Earth, and more displacement of the already poor and marginalized. Not only are Catholic sisters focusing on people living in poverty; they also are focusing on an impoverished Earth.

I am a member of the Sisters of Our Lady of the Missions in New Zealand, which is a very secular country. Less than 9% of the population identify as Sunday churchgoers. But the fact that many New Zealanders live in close proximity to the sea, to the mountains, to the bush and to rivers and lakes means we tend to have an often unspoken awareness of the mystery of the natural world.

As part of a neighborhood group that is committed to the eradication of invasive plant and animal species that are harmful to native flora and fauna, I find involvement in such groups can lead to significant spiritual conversations. Talking about an experience of things spiritual and transcendent in creation with the unchurched is a wonderful way to engage with each other.

Collaborating with the unchurched in a shared journey to care for Mother Earth is a way of being aware of Mystery/Spirit alerting and empowering humankind to reverse the ecological damage for which we are responsible. And it's a great way to live out the ecological dimension of my congregation's missionary activity, which has become a critical component to our work with the poor and the planet, God's gift of creation to us all.

*This story has been updated to clarify that Brian Swimme is a cosmologist, not a theologian.