Guardians of the Atrato River are featured in digital portraits during a Nov. 3 event at the University of Glasgow. The guardians emerged as a result of a landmark ruling by the Colombian Constitutional Court that granted legal rights to the river. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Thousands of miles and an ocean away from home, Maryury Mosquera Palacios brimmed with passion as she described what it means to be a guardian of the Atrato River in Colombia's Chocó bioregion.

"The river is so important for the communities who live alongside it, along with it," she said through an interpreter to a small audience inside Hunter Halls at the University of Glasgow in early November. The agronomist and daughter of an Afro-Colombian leader was one of several panelists at a presentation during the first week of the United Nations climate change summit, COP26.

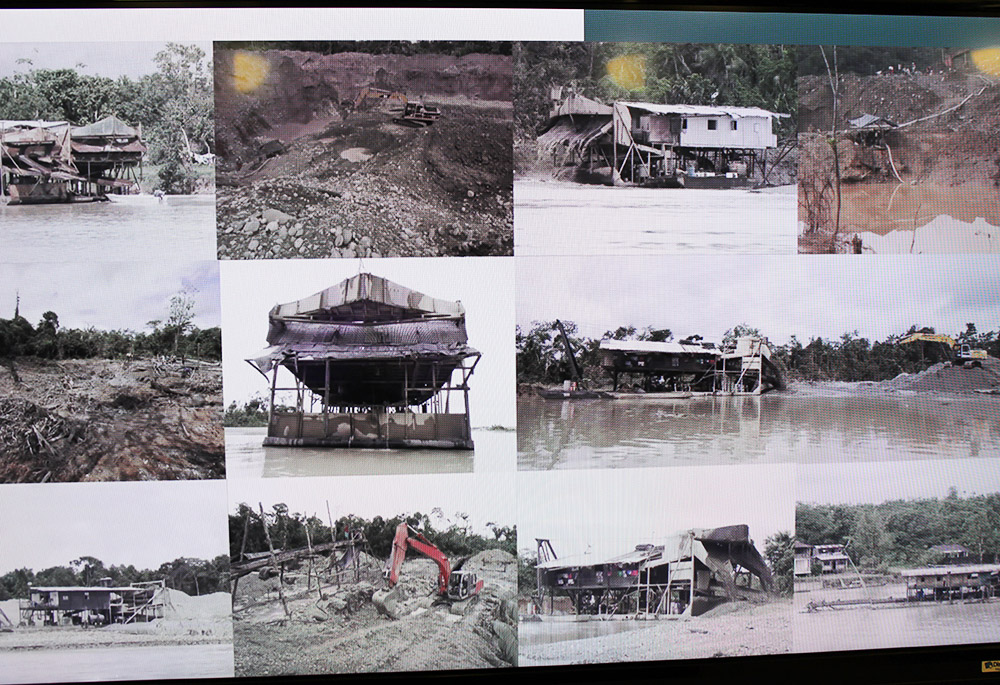

As Palacios spoke, she shared photos of her homeland along the 400-mile river on large screens.

"The river is our washing machine. It's our recreational center. It's our tourist center where we have fun. Our economic source of our wealth, our economy. It's our transport system. And we use it for cultural activities," she said.

How Palacios earned the title of river guardian is the result of Ruling T-622 — a landmark decision delivered in 2017 by the Colombian Constitutional Court that granted legal rights to the Atrato River.

It was the one of the first such court rulings worldwide that granted legal rights to a river.

"It introduced a natural rights precedent, based on the idea that for communities the river is alive," said Viviana González, who represented Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities in the historic court case. "And the support for the cultural life, their spiritual life, the biodiverse life of the region."

From left, Viviana González, a lawyer with Centro Sociojurídico SIEMBRA; Knut Andreas Lid, Caritas Norway program director; Alejandro Perez, Caritas Colombia program director; Mo Hume, profesor at University of Glasgow; and Maryury Mosquera Palacios, technical secretary of the Atrato River Guardians. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

A lifeline flows through the heart of Chocó

The event at the University of Glasgow was organized in conjunction with ABColombia, a coalition of 100-plus partner organizations operating in the South American nation, including several Catholic Caritas-affiliated agencies: the Scottish Catholic International Aid Fund (SCIAF), the Catholic Agency for Overseas Development (CAFOD), representing the bishops of England and Wales, and Trócaire out of Ireland.

Together, they have supported Indigenous communities in Chocó as they sought to defend not just their rights and way of life, but that of the Atrato River as well.

"This case is emblematic and really important because it really brings home to us what Pope Francis talks about in his encyclical 'Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home' … which is looking at the cry of the earth and the cry of the poor as something interconnected," Ulrike Beck, CAFOD's Colombia program officer, told EarthBeat.

"And what we see with the Atratro River and the Atrato River Guardians and those communities, when you talk to them, when you experience what they're doing, is that for them the communities and the river are not divided. They're one of the same. And [what's] important is that we care and protect that connectedness, and that you can't talk about one without talking about the other. And I think that's the big call that we have, especially with the current climate emergency," she said.

While perhaps less known than the neighboring Amazon rainforest, the Chocó region where the Atrato flows is also home to a dense and rich rainforest of its own and is considered one of the 10 most biodiverse spots in the world.

The Rio Quito flows into the Atrato River in this aerial view. In 2017, the Colombian Constitutional Court issued a landmark decision that granted legal rights to the Atrato River. (Courtesy of ABColombia/Steve Cagan)

Located in the northwest corner of Colombia, Chocó connects the South American continent to Panama, and its borders touch both the Pacific Ocean and Caribbean Sea. Combined, those three elements, along with its rich deposits of minerals and natural resources, make Chocó a major geographic center for trade.

Chocó is also one of the wettest places on earth. Within its borders is a massive fluvial system of 15-plus rivers and upwards of 300 other streams. It is a critical carbon sink capable of storing vast amounts of carbon dioxide emissions in its forests and mangroves.

Chocó's five Indigenous tribes have lived there for thousands of years, and its Afro-Colombian communities, which make up the vast majority of the region's population, trace back to the African people brought to the country by the Spanish as slaves.

For centuries, these communities, among the poorest in Colombia, have worked the land in ways that provide for their livelihoods but also protect the territory and respect its limits, González said. Different times of the year are designated for different activities like farming, gold mining and logging.

A collage of images depicts the effects of large-scale mining and logging on the Atrato River region in Colombia during an event at the University of Glasgow, in Scotland, Nov. 3 during the COP26 United Nations climate change conference. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

But the mix of valuable resources and trade routes attracted others to the region. During the 1990s, exploitation of the region exploded as large-scale mining and logging operations accelerated, as did the palm oil industry. The activities and use of machinery like dredging machines and excavators caused significant environmental damage, including deforestation, erosion, biodiversity loss and pollution of the river.

"In Colombia there's a direct link between the environmental degradation and the humanitarian crisis or instability. And there's a vicious circle of more environmental degradation, more conflict, more crisis," said Alejandro Perez, program manager with Caritas Colombia.

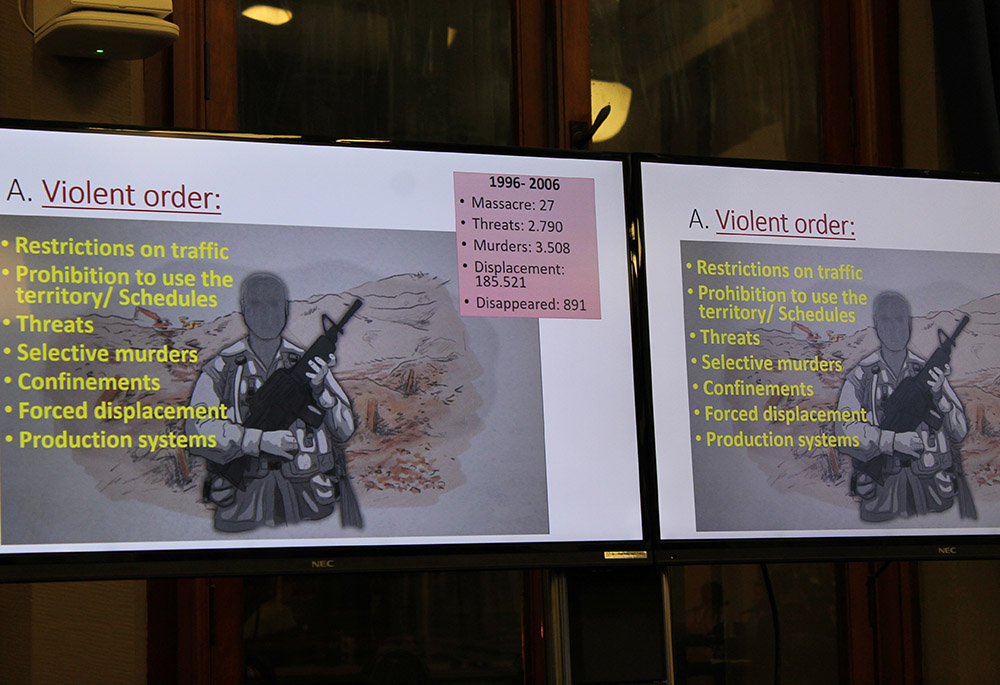

The increase in industrial activity brought with it a rise in armed groups operating in Chocó, whether providing protection for mining and logging companies, as part of the drug trade or paramilitary and guerilla groups engaged in the country's decadeslong armed conflict. According to González, between 1996 and 2006, there were more than 3,500 murders, 891 disappeared persons and upwards of 185,500 people displaced from their homes. The environmental human rights nongovernmental organization Global Witness has ranked Colombia as the most dangerous country for environmental activists the past two years, with 65 environmental defenders killed in 2020, a third of whom were Indigenous or of Afro-descent.

"In a country like Colombia, we can't separate out climate change, environmental destruction, human rights and the peace process," Perez said.

The combination of valuable natural resources and critical trade routes has given rise to armed groups in Colombia's Chocó region. The nation is considered the most dangerous in the world for environmental defenders. (NCR photo/Brian Roewe)

Standing up for the rights of a river

In January 2015, after years of having their concerns ignored by the Colombia government, Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities living alongside the Atrato filed an acción de tutela with Tierra Digna against more than two dozen state institutions and local municipalities. They argued that by allowing illegal mining and degradation of the Chocó biome to continue, the government was violating their human rights, including the right to a healthy environment established under the 1991 constitution.

As their case made its way through the legal system, the Atrato communities received support from numerous groups, including CAFOD, Caritas Colombia and the dioceses of Quibdó, Istmina-Tado and Apartado.

For many who live in Colombia's Choco region, the Atrato River and its tributaries is many things: transport system, economic hub, recreational center and cultural site. (Courtesy of ABColombia)

In May 2017, the Colombian Constitutional Court publicly issued its ruling that the Atrato River, along with its tributaries, is a legal subject and has rights relating to its protection and conservation. It also found that the government was responsible for human rights violations related to the rights to life, water, health, food security and a healthy environment, and the communities' right to free, prior and informed consent.

A major piece of the ruling, Palacios said, was its establishment of biocultural rights, and with them the court's recognition of the role that Indigenous and ethnic communities have historically played in preserving the region's biodiversity and natural resources, and the territorial autonomy they exercise in the region.

"This biocultural approach recognizes the relationship, the inextricable relationship we have with nature with our culture and how we relate within ourselves and our natural environment," she said.

After celebrating the decision, the Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities began working to interpret what it meant. Because the ruling was nearly unprecedented, "there was no model to follow," Palacios said.

Their first move was to raise awareness, in both their communities and the institutions called out in the court's decision. From there, they turned attention to the ruling's fourth order, which called for the creation of a commission of guardians of the river. Originally, it suggested there be two guardians, one representing the community and the other the state, which appointed the ministry of environment. But the communities opted instead to establish a body of guardians of 14 people representing seven organizations stretched along the length of the Atrato. Among them is Palacios, who serves as the guardians' technical secretary.

That group of river guardians was tasked to meet with the environmental minister on a regular basis and with the state institutions named in the court decision to begin complying with its rulings. As part of that process, they arranged for 30 civil servants to travel the Atrato and visit with various communities directly. By December 2019, they had agreed to an action plan with the ministry for environment for implementing T-622's directives about decontaminating and cleaning up the river. They have also worked with the health ministry to conduct toxicology and epidemiology studies.

But challenges have arisen in the five years since the court decision came down.

Advertisement

One has dealt with complying with the order to dismantle illegal mining in the region and prevent toxic substances from entering into the territory, a responsibility assigned to the ministry of defense. Palacios said that rather than remove the massive machines, the military instead burned them, which has led to oil spills and air pollution.

"And then they just leave the husk of the machines in the river," she said.

More broadly, the historical weaknesses of many Colombian institutions, even after the peace accords, has made it a struggle for the river guardians to carry out other aspects of the T-622 ruling. ABColombia described the implementation as "slow to nonexistent at the moment," with the lack of action to halt illegal mining seen as the greatest threat to the communities' safety.

"We have a phrase in Colombia … We have a lot of laws, but they're not implemented and they're not respected," Perez said, adding that ensuring enforcement of the Atrato decision is a role that the international community can play.

In an interview with Caritas Colombia after the ruling, Bishop Juan Carlos Barreto of Quibdó said that one of the main roles the church played was bringing wider attention to the need for actions to reinvigorate the life of the Atrato River and all those who depend on it.

"The processes of enforceability of rights are difficult, they are long, and you have to overcome many stages, persevere and not lose the ability to continue insisting," he said.

We are all river guardians

Another challenge was that the court ruling didn't designate any funding for implementation.

"And that's been one of the biggest limitations we've had as a community, because we haven't had the resources to reach every community given the size of the river basin," Palacios said.

Development organizations, including various Caritas members like CAFOD, have stepped up to provide support through financing and resources for information on the ruling, Beck said.

In their outreach to communities along the Atrato, the river guardians have focused on education and advocacy campaigns to raise awareness and understanding about the court ruling and its implications. They have developed a website, a local newspaper, infographics and a social campaign called "We Are All Guardians of the Atrato."

A child looks out on the Atrato River in the Chocó region of Colombia. (Courtesy of ABColombia)

They have especially targeted young people, because "those are the future officers of the community council and Indigenous authorities and they're also the future stewards of the territory," Palacios said.

But the work of defending the Atrato isn't limited just to those who live near the river. As well as Catholic development groups, the river guardians have met with U.N. delegations and different embassies, and sought to build new partners during their time in Glasgow at COP26.

In concluding her remarks, Palacios led the audience in reciting a slogan conceived by a priest who's acted as a counselor and adviser to the communities in their yearslong pursuit of winning rights for their lifeline of a river: "Atrato soy. Atrato somos, y Atrato debemeos seguir siendo."

"I am Atrato. We are the Atrato. The Atrato is. And we should continue to be the Atrato."