(Unsplash/NASA)

Back in the 1970s, when I was in my 20s, I was part of a community living at the Grail's national center on an organic farm in rural southwest Ohio. A tall, thin priest used to come visit us from time to time. He seemed quite old and wobbly to me, and I worried that he might fall off the steps on his way up to the altar to celebrate the liturgy.

The priest's name was Thomas Berry, and in recent years, I have been forced to admit that my concerns about his age and wobbliness — he was in his mid-60s at the time — were a bit off-point. And that his portrayal of the new story of the universe, shared with us in mimeographed form before he began publishing about it, was a great deal more significant.

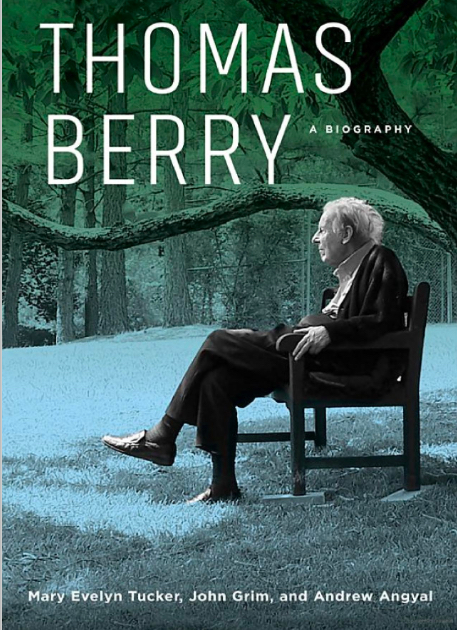

The new biography of Berry by Yale's Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim, with Andrew Angyal, confirms big-time my revised estimation of that tall, thin priest. Berry, who in later years described himself as a "geologian" rather than as an eco-theologian, presented a vision of the universe, of all of creation, and of the Great Work we are called to within it. Such a vision was revolutionary for his time and is even more relevant to the current planetary crisis than it once was.

As detailed by the authors, Berry was born in North Carolina, to a prosperous family, and fell in love with nature at an early age. His early experiences of a numinous creation shaped his life's work. After attending a boarding school run by the Passionist Order and a year of college, he entered the Passionists, drawn in particular to their commitment to the suffering of the world. He eventually added a fourth vow to the three made by all Passionists: dedication to the passion of the Earth.

Berry was in large part a scholar, and the scope of his knowledge is mind-boggling. After seminary, he earned a Ph.D. in European cultural history, writing a dissertation on Giambattista Vico's universal philosophy of history. He went on to study Asian religions and cultures, learning Sanskrit and publishing books on Buddhism and the religions of India. He directed the graduate program in the history of religions at Fordham University. He also founded the Riverdale Center for Religious Research, one of the bedrocks of religious environmentalism.

Advertisement

Furthermore, by the early 1970s, Berry was researching the cosmologies of native traditions, highlighting their "symbolic ways of knowing the interrelationships between bioregions … and the larger universe." The authors argue that the impact of indigenous worldviews on Berry was so profound that he became a shaman as well as a scholar. Also enormously important for Berry's thinking was the work of Jesuit Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the paleontologist and theologian of the cosmos.

Out of this extraordinary breadth of knowledge, Berry fashioned a cosmic, utterly compassionate vision of the universe. Fundamental to that vision was his conviction that a new narrative of the universe was essential to change. Only human understanding of the history of the ever-expanding universe would lead us out of our era of planetary destruction and mass extinction into a more compassionate, sustainable era. So enormous would the effort be that was required to move humanity into this new era in politics, economics, culture and religion that Berry called that effort the Great Work. Deeply hopeful, he continued throughout his life to trust that humanity would indeed take on this Great Work and move beyond planetary suicide to embrace its vital role as part of an interdependent "communion of subjects."

The authors also show that along with his massive contributions to our comprehension of this cosmic intercommunion, Berry impacted the wider society in other significant ways. At a time when the concept of a new geologic era, marked by human impact on and damage to the planet, the Anthropocene, has taken center stage, Berry's earlier concept of an Ecozoic Era, an evolutionary phase of mutually-enhancing relationships between the planet's ecosystems, provided a prescient alternative.

Berry also introduced the idea of legal rights and representation for the planet itself in response to widespread violations of those rights. This notion subsequently developed into the legal field of "earth jurisprudence," now taught in law schools and studied widely. And Berry's characterization of the domination and exploitation of the Earth through technological mastery as the "Technozoic" alternative to the Ecozoic Era, may well have laid the foundation for Pope Francis' critique of the "technocratic paradigm" in "Laudato Si', on Care for Our Common Home." Finally, Emmy-award winning 2011 film, "The Journey of the Universe" created by Brian Swimme with Tucker and Grim was dedicated to Berry and introduced many thousands of people to his profound ecological cosmology.

As well written and informative as the Grim, Tucker, Angyal biography of Berry is, I find one aspect of it puzzling: There is not a criticism of Berry or his work in the entire book. No mention, for example, of his economic privilege — attending a Catholic secondary boarding school in the 1930s when most U.S. Catholics were on the breadlines or in the Civilian Conservation Corps — and the connection between that privilege and his ability to spend his life studying the admittedly crucial subjects he did. And no mention either of the irony that the father of someone who dedicated much of his life to fighting planetary destruction was the owner of an oil company.

Perhaps the fact that two of the authors, Tucker and Grim, were Berry's students and deeply influenced by him over many years explains this absence of critique. Parts of the book read almost like a memoir of their collaboration with him.

At another level, though, the gratitude and admiration the authors express for Berry's life may well be a reflection of the cosmic, compassionate, unifying vision that underpins his entire body of work. Berry saw that everything in the cosmos is one, articulating the communion between groups, species and material entities that today are all too often seen as hostile opposites. Out of this cosmic worldview the authors constructed an interpretation of Berry's life that is positive, hopeful and badly needed.

[Marian Ronan is research professor of Catholic Studies at New York Theological Seminary in New York City. Her most recent book, with Mary O'Brien, is Women of Vision: Sixteen Founders of the International Grail Movement (Apocryphile Press, 2017).]