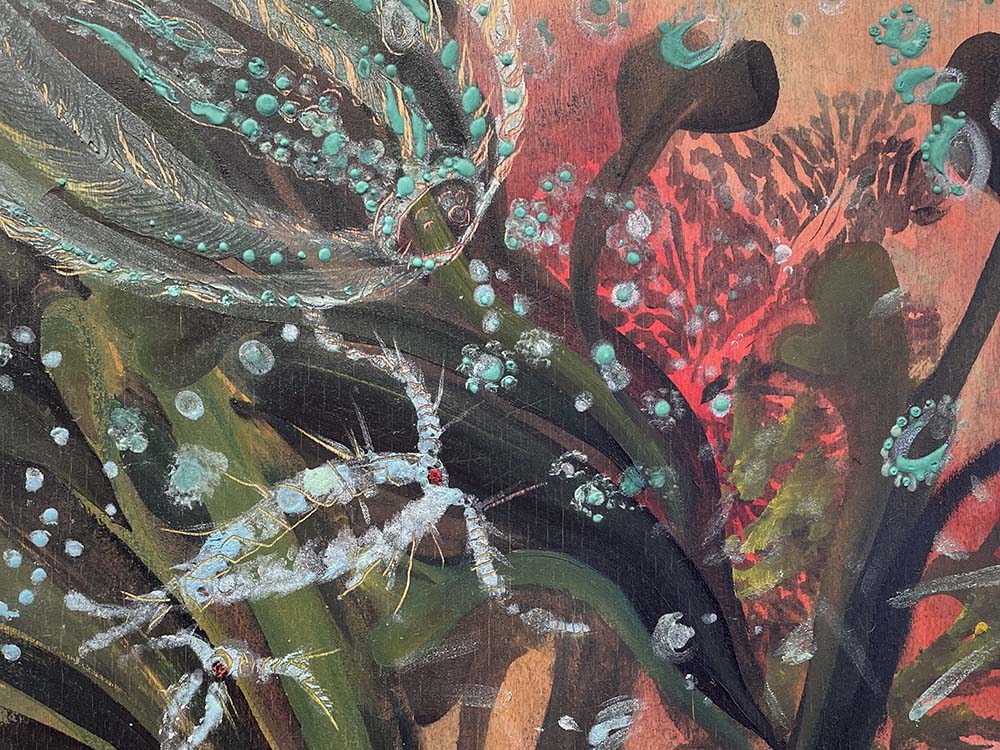

"Intertidal Zooplankton Dreaming" by Krisanne Baker (Jim McDermott)

Ten years ago, artist Marcia Annenberg wondered why she wasn't seeing more art related to the environment in galleries. So she sent out a call to the Women's Caucus for Art.

"Six hundred people responded," she told me, astonishment still in her voice. From them, 72 were chosen for "Petroleum Paradox," a national exhibit in New York.

Since then, Annenberg has curated three other exhibits inspired by the environmental crisis, including the provocative new "Earth on the Edge: 12 Artists Declare a Climate Emergency" at the Ceres Gallery in Manhattan. The works, on display Dec. 16-24, vary from acrylic painting to sculpture, and from pop art whimsy to a sort of reverent awe. But many of the pieces seem to invite viewers into a quiet contemplation of loss.

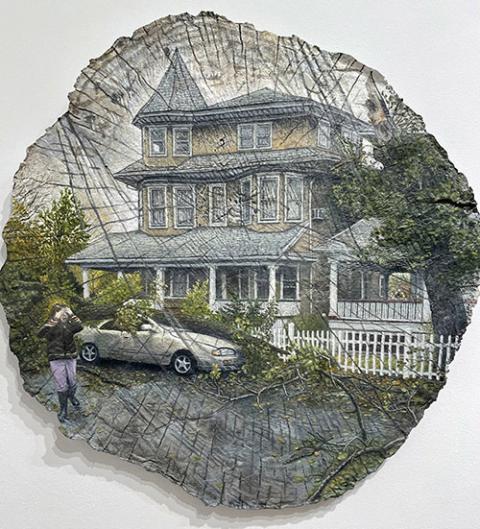

"Lament (After Sandy)" by Kathy Levine (Jim McDermott)

"Everything's feeling the same kind of dread," says Annenberg. "We're not responding quickly enough."

At an opening reception Dec. 16, the first installation I note upon entering the room — a series of paintings on recycled paper from Kathy Levine — depict scenes of downed trees and home wreckage in the wake of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Levine has crafted the work to appear as though it's been painted on cross-sections of a tree trunk. It gives these moments a strangely spectral quality, like we're catching a glimpse of events and people who no longer exist.

Meanwhile, in the next room, iconographer Angela Manno, who studied Byzantine Russian iconography for 20 years, has created a set of a dozen small icons of threatened or endangered species. The images are gorgeous and varied, from the pink flamingo and the monarch butterfly to the scaly pangolin and the star cactus.

But what unites them is the wonder and sadness they inspire. Even though none of these species is yet extinct, a sense of inevitability hangs over them. Paradoxically, the effect has something to do with the tremendous amount of presence that Manno achieves in the work; they're so fully realized they seem that much more precious and fragile.

"Loggerhead Sea Turtle" by Angela Manno (Jim McDermott)

Intriguingly, Manno's desire to create such images emerged from a problem she started to have in her study of iconography.

"Pretty soon into it I felt like there was something missing in the canon," she explains. She realized that it was the practice's sole focus on the relationship between the human and the divine. "Nature is kind of relegated to the background," she noted.

In the theology of St. Thomas Aquinas, she found an important corrective. "Because the divine could not image itself forth in any one being," Aquinas wrote, "it created the great diversity of things so that what was one lacking in one would be supplied by the others and the whole universe together would participate in and manifest the divine more than any single being."

"It's not just human beings that are the image of the divine," Manno says. "It's the whole of creation."

At the other end of the spectrum of tone and sentiment in the exhibit stands a playful papier-mâché work by Simone Spicer. Using Hokusai's famous print "Under the Wave of Kanagawa" as inspiration, Spicer built a three-dimensional model of the wave and filled it with toy figurines. SpongeBob SquarePants, Cookie Monster, Jay and Silent Bob, R2-D2 and Charlie Brown's nemesis Lucy van Pelt are among the hundreds of characters presented on top of and within the wave, happily surfing together.

At first glance, the result is a joyous raucousness — all our favorite pop culture characters on a summer holiday. But as you step back from the individual characters, you begin to notice the wave itself, which hangs over them all.

"The End of the Age of Innocence on the Great Wave of Kanagawa" by Simone Spicer (Jim McDermott)

The fact is, they're all moments away from being decimated. Their happiness is actually horrifying, and our initial delight in the work likewise ends up making us question ourselves and our own obliviousness. (And yet even understanding this, still we can't stop looking at it and enjoying it. The work truly forces us to confront just how deep our capacity for denial goes.)

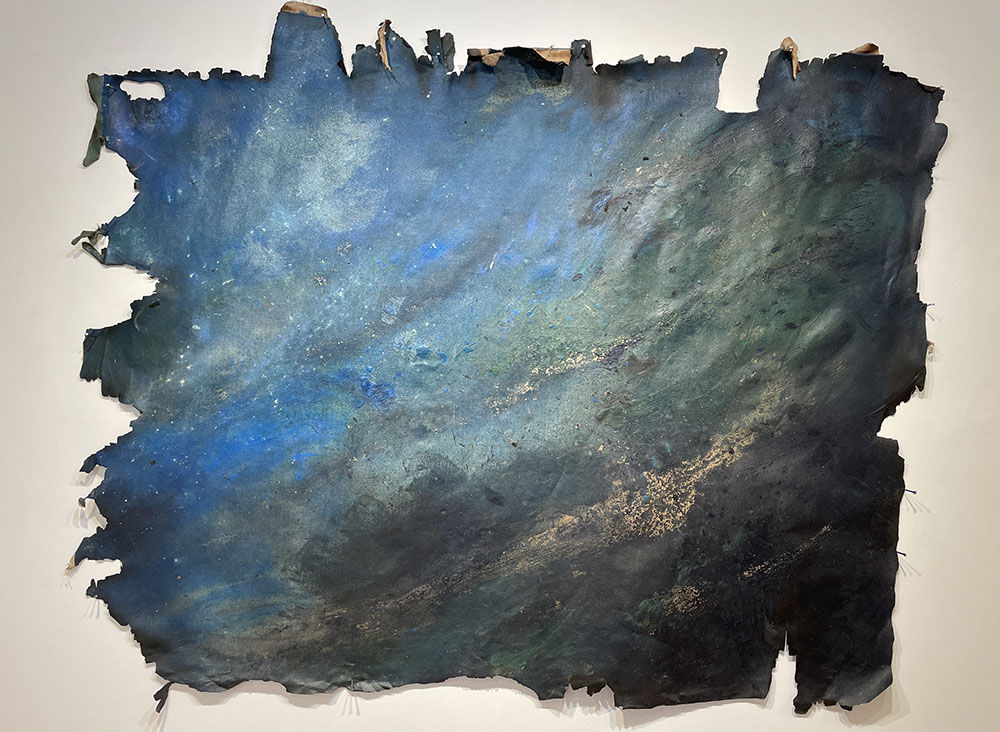

On the wall to the left of Spicer's wave, Annenberg has included a large abstract painting from Noreen Dean Dresser. The inviting deep blues of the left side of the work suggest either an oceanic or astral theme. But as the eye moves from left to right and from top to bottom, the image grows more and more soot-black; and the edges of the painting likewise have a ragged, burnt quality, as though this is all that remains of something much larger.

Dresser explains that the inspiration for the work was the Deepwater Horizon oil spill that poured 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010.

"I was horrified," she says of the accident.

"Oil and Water" by Noreen Dean Dresser (Jim McDermott)

The black sediment and the ragged edges of her painting are a product of real oil and fire being applied to the work. "I wanted the painting to have those forces in play," Dresser says. "You can see the ash here, the burning ... and it's all coming in on these waters."

Dresser's artwork always has an ethical dimension, she explains. "I think art is a place where people can have a conversation."

And all of the artists present at the grand opening gala of "Earth on the Edge" seem driven by a desire not only to present their work but to talk with and educate patrons about environmental issues.

Biologist and research scientist Nigella Hillgarth, whose photographic work overlays images of the ocean waves with shots of the invisible-to-the-eye microbes being emitted by them, explains the changes going on within the chemistry of the ocean.

For each of the icons Manno paints, she has a story about the cause of their endangerment, and sometimes the things being done to save them.

Advertisement

The curator Annenberg struggles to get her head around the world's lack of urgency in stopping deforestation.

"The folly of what they're doing" in the Amazon, she says. "They're clearing the trees to make crops, but because there's less trees, there's less rain so there's less moisture for the crops. It's so short-sighted, it's mind boggling."

About an hour into the opening reception, artist Krisanne Baker calls for a moment's attention. It turns out her work, a series of portraits of spooky-looking phytoplankton, has been done in part in paints meant to capture the lifeforms' bioluminescence. The effect when the lights go off is extraordinary in its graduality. The glow of the paints comes on so slowly as to create a dawning sense of wonder in the room. This beautiful and delicate life has been here all along and we just didn't see it.

In a sense, Baker's work captures the spirit of so much of the intention in the art presented here, and also the inner life of the artists themselves.

"I start every day with a blessing," Dresser tells me. "I end with a blessing. Because I get it, it's a gift."

I wonder whether she's always seen life this way or whether something taught her that. "I don't know," she says when I ask. "I live with a profound sense of gratitude."

Then a memory comes: "I'm of that generation, I'm 69. When I was a kid, AIDS came. One year I lost 39 friends. We were young, but death was everywhere, and scary."

Looking at the crisis confronting our entire world, the artists of "Earth on the Edge" invite patrons into a similar moment of both awe and clarity.