Mee-Kai Spottedhorsechief, a Pawnee, is in a garden of white flour corn in Nebraska. On the back of her neck is a tattoo of Pawnee four-pointed stars. (Ronnie O’Brien)

After years of working for secular conservation organizations, ecologist Bill Jacobs noticed a deficit in their approach. The planet's environmental problems reflected a profound moral and religious crisis that neither science, politics nor economics could fully solve. "It occurred to me we weren't going to save nature without some reference to God," he said.

Jacobs is now the executive director of the St. Kateri Conservation Center, which he established in 2000. For more than 15 years, the Center remained an online repository of Catholic resources on ecology — apolitical and funded by donations. With the recent addition of two women as volunteer staff, the St. Kateri Conservation Center has expanded to include practical programs promoting conservation and ecological restoration as expressions of faith.

"We live in a somewhat sick world where we have lost connection with ourselves, God, our little brothers and sisters [plants and animals]," Jacobs said, adding that the work of the Center is to restore these relationships. He thinks a Catholic ecology is well-positioned for the task.

"Ecology is the study of living organisms in relationship to one another. The Catholic faith is also a religion of relationships. God himself is a relationship. God has the Trinity," said Jacobs, who is also the co-founder and program manager of the Long Island Invasive Plant Species Management Area, or LIIMSA, which contracts with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

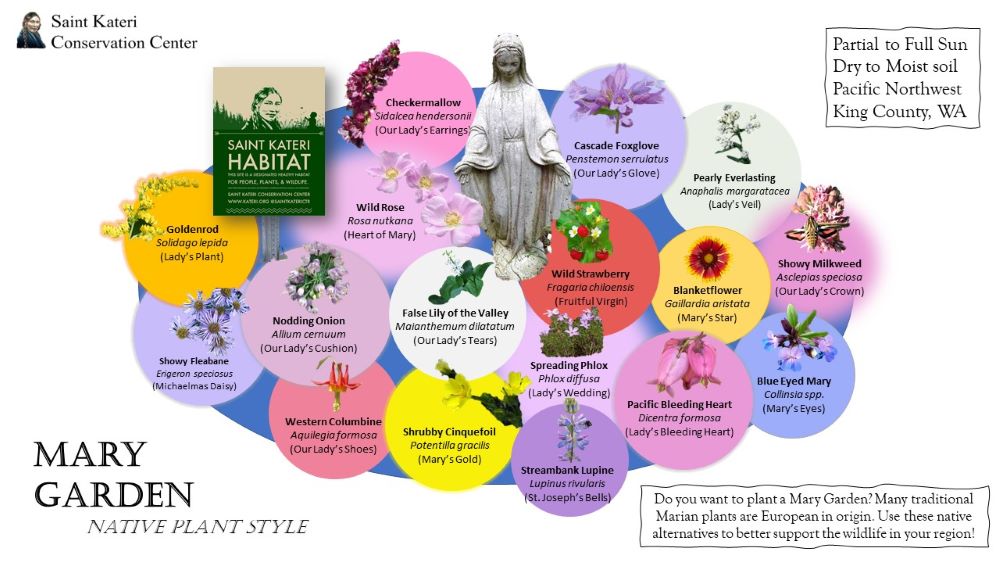

The St. Kateri Conservation Center’s pacific northwest Mary Garden design was designed by their horticulturist, Annalise Michaelson. (Courtesy of Kat Hoenke)

Catholic ecologist Kathleen Hoenke described the Center's mission as twofold: to highlight the Catholic-stewarded properties that are engaged in ecological conservation and those that could be. A spatial ecologist, she works as a geographic information systems, or GIS, coordinator for the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership, a regional organization that covers 14 Southeastern states and is focused on protecting and restoring aquatic systems. While out mapping dams one day, she had a eureka moment.

"I realized — Wow! — the church has a lot of land being stewarded by people of faith," she said. "Yet these people were not connected to the conservation community. Why not link them?"

That revelation inspired the creation of the St. Kateri Habitats and Parks Program, which Hoenke and Jacobs launched in 2018 to encourage the cultivation of wildlife-friendly spaces that feature native plants and provide a place for prayer and meditation. Today, the program has registered nearly 200 habitats on five continents. Most are in the United States, but the registry also includes an Australian sheep farm, an alleyway garden in the city center of Poznan, Poland, a tree nursery in Cameroon and an eco-village in the Mauritian Islands.

'It occurred to me we weren't going to save nature without some reference to God.'

—Bill Jacobs

Any landscape — from patio pot to forest — can qualify as long as it meets a few modest requirements: food, water and cover for wildlife; native trees, shrubs or herbaceous plants; ecosystem services such as pollination; sustainable practices in gardening or land management; and a sacred space for prayer and worship. The program guidelines posted on the Center's website encourage participants to incorporate a religious expression in their habitat — a cross, statue or St. Kateri Habitat sign that the Center provides — to remind them the Holy Spirit is "present and active in every corner of creation."

The Catholic initiative is part of a growing movement to mitigate climate change and biodiversity collapse by enlisting gardeners, farmers, homeowners or any land managers in the work of ecological restoration.

Doug Tallamy, a leading proponent of this grassroots approach to conservation and an entomologist at the University of Delaware in Newark, writes in his books about the specialized, intricate relationships that make up the natural world and how habitat loss has precipitated drastic declines in wildlife populations. The pesticide-managed lawns and exotic plants common to many neighborhoods are dead zones for the myriad insects that once fed on native grasslands, oaks or paw paw trees. Insects, those "little things that run the world," as naturalist E.O. Wilson called them, are fundamental to the food web. Without them, the earth's ecosystems will collapse.

Tallamy's solution is to reincorporate native plants across the lawnscapes of America. His aspirational project, "Homegrown National Park," envisions Americans transforming backyards, city streets, parks, uninhabited woods and even window boxes into corridors of wildlife conservation.

Catholics can contribute significantly to this effort, Hoenke says.

A statue of St. Francis of Assisi stands in Bill Jacob’s yard. (Courtesy of Kat Hoenke)

One of the designated habitats in the St. Kateri Habitats and Parks Program is a 26-acre plot of forest and gardens in the Adirondacks that supports the monarch butterfly population. Climate change and habitat loss currently threaten the species, but at this St. Kateri locale, a pollinator garden of bee balm, sunflowers, evening primrose, zinnias and milkweed — the only plant upon which the monarch lays eggs — provide a hospitable spot for the insect, as well as "many species of caterpillars and bees," reads a description of the site posted in the St. Kateri Habitats registry.

"We need thousands of these habitats," said Jacobs, who hopes to have at least one at every U.S. parish.

As part of its habitat program, the Center provides regionally specific designs for a native version of the Mary Gardens commonly found on church grounds.

"Religious orders have been thinking ecologically. It's the parishes that could use the help," Hoenke told EarthBeat. "We will use GIS to identify the large properties that are more naturally covered with wetlands and forests so we can reach out to them."

Kasey Butcher Santana registered Sol Homestead, a micro-farm she and her husband tend in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, as a Saint Kateri Habitat in 2021. The couple raise alpacas, chickens and honeybees. Native columbine grows on the property, as did a Colorado blue spruce until the alpacas ate it. They plan to plant another.

"I see this as a way to put Laudato Si' in action. Care for our common home starts at home," Butcher Santana said. She likes the St. Kateri Habitat's emphasis "on gentle care of the earth" and appreciates the Catholic element. "We have our little St. Francis statue," she said.

"Interacting with our garden and our animals, especially for me the bees, brings such a source of wonder and calmness," she added. "I think there are a lot of sources of anxiety in the world, and connecting with our Creator brings calmness."

Deb Echo-Hawk and Ronnie O’Brien harvest blue flour corn in Nebraska in 2019. (Ronnie O’Brien)

St. Kateri Indigenous Peoples Program

Jacobs initially considered naming the Catholic conservation center after St. Francis, but opted instead for the American St. Kateri of Tekakwitha, to emphasize the importance of reconnecting with Indigenous peoples. Kateri's mother was Mohawk/Catholic and her father an Algonquin chief. Canonized in 2012 as the first Native American saint, she is the patron saint of ecology and of Indigenous peoples.

"In some conservation circles, everything is a plant or animal. We have to consider the humans. We have to include Indigenous people, or we are cutting out some people," Jacobs said.

Three members of the organization's women-majority board of directors are Indigenous — one has Indigenous ancestry from the Andes mountains in Peru, one is a member of the Mohawk Nation and one is a registered member of the Oglala Lakota tribe in South Dakota. Ronnie O'Brien, a Nebraskan educator, directs the St. Kateri Indigenous Peoples Program, established in 2019.

For the past 20 years, O'Brien has partnered closely with Deb Echo-Hawk, the former director of K-12 education for the Pawnee Nation and a seed-keeper for the tribe, in her efforts to rejuvenate ancient varieties of Pawnee corn.

In the 1870s, many Pawnee were expelled from their ancestral homelands in Nebraska and relocated to Oklahoma, which is where Echo-Hawk tried to grow corn from kernels her family had preserved for generations. Oklahoma's red clay proved inhospitable to seeds cultivated for a millennium in black Nebraskan soil. Her efforts floundered until O'Brien offered to plant the seeds in her home state, returning the harvest to the Oklahoma tribes each fall.

This is Bill Jacob's yard. He is executive director of the St. Kateri Conservation Center. (Courtesy of Kat Hoenke)

Echo-Hawk initiated the Pawnee Seed Preservation Project (now the Pawnee Seed Preservation Society) in 1998. O'Brien began collaborating with her in 2003. When the collaboration began, the women struggled to establish two varieties of native corn. They say they have since revived more than 20. As coordinator of the St. Kateri Indigenous Peoples Program, O'Brien hopes to replicate the project with other tribes. The program seeks to connect Catholic landowners of tribal homelands with tribal seed cultivators in order to provide hospitable land for nurturing ancient varieties of crops.

"We want Catholic brothers and sisters to provide the land," O'Brien said, stressing that cultivation would be "100% under the guidance of Indigenous seed-keepers." Her work with Echo-Hawk brought a deeper consciousness of God's presence in nature and reconciliation, she said.

Advertisement

"As someone who is a descendant of pioneers and knowing what happened to the Pawnees because of my ancestors, there is a reconciliation, a reconnection to a people, to their homeland, to their friendship," O'Brien said.

It's the kind of holistic ecological restoration Jacobs advocates — a reconnection of humans to the earth which in turn reconnects them to God and each other. Asked about the climate crisis, he admits it's dire. But he doesn't think fear will motivate people for the change required. Love will, he says. And as Jacobs sees it, that love throbs everywhere.

"There is a transcendence out there," he said. "We live in a world where the Holy Spirit is present and active in everything. To be an ecologist and to not notice that, to not notice anything beyond the physical science alone, is a mistake."