People in Warsaw, Poland, celebrate Sept. 29, ahead of the Nov. 11 centenary of Polish independence. (CNS/EPA/Marcin Obara)

When Poles celebrated the centenary of their regained statehood this November, politicians and church leaders used the occasion to reaffirm the country's unity with Europe and commitment to democracy.

But as other countries of Eastern Europe also commemorate the centenary of their independence after World War I, concern is growing over claims of a new upsurge in nationalism and authoritarianism in the region.

Some fear current tensions could spur a new East-West rift, calling in question ties carefully nurtured over the three decades since communist rule.

"People want to be themselves here, with their identities and rights respected. If Western officials won't accept this, we're sure to face a crisis," said Jan Zaryn, a Catholic historian and Polish senator. "But the Western media gains its information from narrow sources and seems uninterested in a fuller understanding. Though not all viewpoints have to be taken up, they should at least be listened to."

In Poland's case, the cause of conflict has been clear.

When the Law and Justice party, headed by Jaroslaw Kaczynski, won an election landslide in October 2015, it made good its pledges to help citizens excluded from the benefits of economic liberalization, by lowering the pension age, helping the disabled and supporting large families.

But it also courted controversy with plans to tighten control over state television and radio appointments and to reform the justice system by retiring long-entrenched judges.

Law and Justice party supporters insist previous governments had also had a hand in appointing media directors and judges and that top-level replacements were needed, since the outgoing Civic Platform, in power for eight years, had saturated the country with its appointees.

But the Civic Platform disputed this and turned to the European Union, insisting the new government's reforms would centralize power and infringe civic freedoms.

Sanction threats followed from the European Union, where the Civic Platform's former premier, Donald Tusk, is president of the intergovernmental European Council. In November 2017, the European Parliament duly recommended Poland's suspension from decision-making.

Poland is not alone in facing Western pressure.

Further south in Hungary, the center-right government of Premier Viktor Orban also faces action for breaching EU core values under a European Parliament resolution, which accused it of mistreating minorities and violating the rule of law.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban in Brussels on June 28 (Wikimedia Commons/European People's Party)

Amendments to Hungary's Basic Law, passed overwhelmingly by the Budapest Parliament in June, criminalized public homelessness and threatened jail for anyone helping "illegal immigration," while also obliging future Hungarian governments to "defend Christian culture."

Measures like these have rung alarm bells around Europe. But when the European Parliament's report was published in September, Hungary's secretary for EU relations, Judit Varga, insisted it was "riddled with factual errors" and steered by "liberal fundamentalism," reflecting "a bias against contemporary European conservatism, national sovereignty, core Christian-democratic values."

"The European Parliament has engaged in a political witchhunt that lacks common sense and highlights its inability to respond to complex issues," Varga wrote in an op-ed published in Politico. "Hungary has become an 'issue' for the simple reason that some of its national policies run against mainstream EU institutional logic and memory."

The European Parliament is also "deeply concerned" about neighboring Romania, where Liviu Dragnea, the strongman behind the current Social Democrat government, has faced sentences for electoral fraud and abuse of office.

In early November, first vice president of the EU's governing commission, Frans Timmermans, accused Romania of reversing progress achieved since it joined the EU in 2007, while Britain's lofty Financial Times charged the Romanian government with "undermining the rule of law" and sowing doubts about "the credibility of the nation's basic institutions."

Like her Polish and Hungarian counterparts, Romania's premier, Viorica Dancila, has rejected the criticisms, accusing EU officials of not giving a full picture of the situation in her country.

So has the Czech Republic premier, Andrej Babis, who faces resignation demands over alleged corruption, and has repeatedly warned the EU against imposing unpopular policies on Eastern Europe.

The Czech Republic makes up the "Visegrad Group" with Hungary, Poland and Slovakia, whose leaders have argued for strong national government and opposed calls by French President Emmanuel Macron and Germany's Chancellor Angela Merkel for closer EU integration.

All four have also resisted EU quotas for the resettlement of Muslim refugees, insisting the EU's real aim is to enforce a liberal, secular agenda in place of Eastern Europe's Christian traditions.

Zaryn, the Polish historian, thinks a bigger struggle is brewing, as societies from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, which were previously held in tutelage by their richer Western neighbors, now come into their own and reassert their own identities.

"Poles and others have long memories, and the language of attack being used to deter us from defending our interests won't generally have much effect," Zaryn told NCR.

"Of course, there are distinctive political traditions here, from independent socialism to Christian communitarianism," Zaryn said. "But it's intellectually dishonest to brand these populist and nationalist and try to link them with fascism and Nazism, especially when people here fell victim to these murderous ideologies. This won't build tolerance and understanding."

Given its strong presence in Eastern Europe, some observers think the Catholic Church should be doing more to help stem the East-West bickering.

'People want to be themselves here, with their identities and rights respected. If Western officials won't accept this, we're sure to face a crisis.'

—Polish Sen. Jan Zaryn

Visiting Poland in August, as the EU Commission gave the country a month to abandon its reforms, German Cardinal Gerhard Müller, former head of the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, urged the West to show greater respect for democratically elected leaders. Müller advised Poles not to "take lessons on democracy and freedom from politicians in Brussels or Strasbourg."

To date, however, Eastern Europe's Catholic bishops have rarely spoken out.

In August, when Romanian police used tear gas and water cannons to disperse protests against corruption and mismanagement under Dancila's government, the Catholic bishops declined to join the Orthodox Church in condemning the disturbances.

Hungary's primate, Cardinal Peter Erdo of Esztergom, has defended Orban's espousal of Christian values to put forward his vision of an "illiberal democracy" — which has included a 2017 Asylum Act permitting refugees to be barred with razor fences and armed police.

The creation of a new "national ideology" could be the best antidote to the "cultural and ethical vacuum" left by communism, Erdo told a Vienna audience in February, as well as to the "moral relativism" destroying the West.

"Functioning law requires ideological and ethical supports which enjoy wide social acceptance," explained Erdo, who chaired the Swiss-based Council of Catholic Episcopates of Europe for a decade up to 2016. "It's understandable political leaders in some of these countries are now seeing relativist ideologies as less attractive and seeking to rebuild society's cultural and religious foundations."

Beyond that, however, the Hungarian church has refused any collective comment on government actions, or on the Western criticisms directed against them.

Left: Cardinal Peter Erdo of Esztergom-Budapest, Hungary, celebrates Christmas Mass in 2016 (CNS/EPA/Attila Kovacs). Right: Czech Cardinal Dominik Duka of Prague in St. Peter's Square at the Vatican in May 2017 (CNS/Paul Haring).

Erdo's Czech counterpart, Cardinal Dominik Duka of Prague, deplored the October 2017 election of Babis' Action of Dissatisfied Citizens party as a defeat for pro-EU parties, and said he counted on his country's new rulers to uphold legality.

"Victory has gone to parties and movements who played no part in creating our freedom over the last 25 years — I'm not even sure whether it's the left or the right who won," Duka said in a statement. "Since they've all committed serious affronts to our constitution, it's clear we ourselves will be the greatest enemies of democracy if we don't act as honest citizens and take responsibility for the common good."

In neighboring Slovakia, the bishops' conference president, Archbishop Stanislav Zvolensky of Bratislava, marked the centenary of Czechoslovakia's creation in September, acknowledging that the united state had brought democracy but also centralized power at the expense of Slovaks and their Christian heritage.

Having gained their own state in 1993, Catholic Slovaks now had the possibility of living "in a spirit of freedom and justice" with other nations, Zvolensky added.

Here too, however, no direct reference was made to current issues — a reticence that has also characterized the usually forceful Polish church.

Although widely thought to be supporting the current government, Poland's bishops have, in reality, been careful to avoid direct involvement. And while top officials, from President Andrzej Duda down, conspicuously attend Catholic events, few clergy have attracted media attention, as they once did, by speaking up for Kaczynski's party.

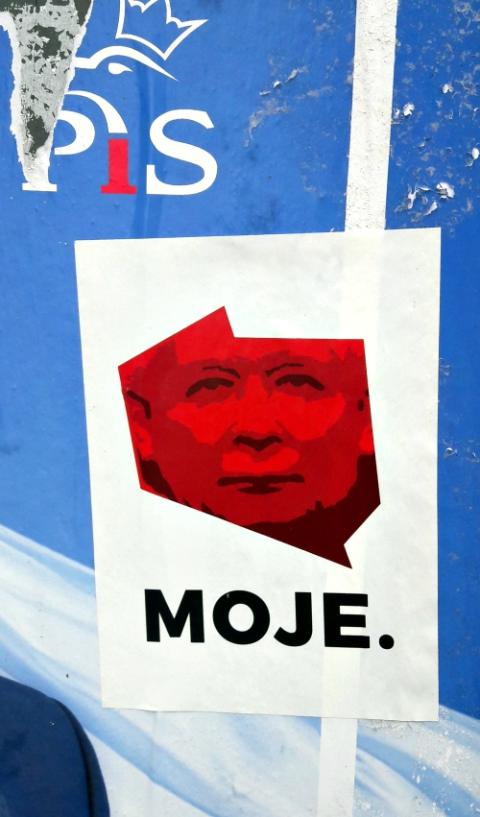

A picture of Jaroslaw Kaczynski and the logo of his Law and Justice party are seen on a wall during local elections in Poland Oct. 7. (Wikimedia Commons/Silar)

Given the Law and Justice party's public defense of Catholic teaching, most bishops have naturally viewed it sympathetically. But they've said little about Poland's current dispute with the EU, beyond appealing for more temperate political debates.

There have been some exceptions, such as in June, when the bishops' conference president, Archbishop Stanislaw Gadecki of Poznan, celebrated the 1,050th anniversary of Poland's first Christian see by accusing Europe of "flabby totalitarianism" and a "dictatorship of materialism."

But in March, as Poland and Hungary faced EU sanctions, Gadecki warned politicians in both countries against fostering negative prejudices.

"The patriotism and the love of homeland that characterize our nations is a great value," Gadecki told a congregation that included Duda and Hungarian President Janos Ader at Veszprem, Hungary. "But we must constantly take care it doesn't give rise to an unhealthy nationalism, xenophobia or contempt for others."

The same restrained approach was evident when the Polish bishops issued a pastoral letter in early November to commemorate Marshall Jozef Pilsudski's restoration of a Polish republic in 1918, following the collapse of the German, Austrian and Russian empires, which had partitioned the country since the 1790s.

Independence required not just "armed struggle, and political and diplomatic efforts," the text emphasized, but also "resolute faith and prayer."

"Our homeland's painful history should sensitize us to threats to the nation's spiritual freedom and sovereignty," the bishops wrote. "The gravest of these arise from abandoning the Catholic faith and the Christian principles governing our national life and state's functioning. This has already led in the past to our republic's collapse."

Asked about media criticisms that the letter had bypassed current problems, Polish bishops' conference spokesman Fr. Pawel Rytel-Andrianik told NCR it had not been the right occasion to discuss wider controversies.

"Our independence was prayed for, worked for and fought for — both by internal effort and military force," he said in an NCR interview. "The bishops' aim was to throw light on these events a century ago, rather than cover more recent developments. Not everything can be dealt with in a short pastoral letter."

Some observers think the reticence reflects the rival narratives currently at play, and the church's unwillingness to be seen as taking sides.

Advertisement

The European Commission's Timmermans claims to have identified 13 breaches of EU core values in the Law and Justice party government's program, alongside systemic threats to fundamental rights. Those who take such warnings seriously will naturally consider it vital to speak out in defense of democracy and the rule of law.

Others, however, insist that complex government positions are being misrepresented by EU critics, who are tabling dramatic charges as a political tool to support the liberal opposition.

They say the Law and Justice party government has a solid record of long-delayed economic and social improvements and has also taken a tough pro-NATO stance on defense and security, including modernizing Poland's armed forces and an active involvement in international peacekeeping.

Having supported the EU's eastward expansion in 2004 and after, the Catholic Church has good reason to be more skeptical today. In the 14 years since, EU politicians have backed measures widely seen as hostile to Catholic teaching, including abortion and euthanasia, same-sex marriage, and gender realignment.

Yet the church has benefited substantially itself from EU development funds — a fact recalled by the Czech bishops at their October plenary — and will be reluctant to take on the EU directly.

It knows further polarization will bring comfort to Russia and those conspiring to undermine East-West unity, by weakening the continent's institutions and undermining its shared aspirations.

A Christmas tree is illuminated as people visit the traditional Christmas market Dec. 2 at the Old Town Square in Prague, Czech Republic. (CNS/Reuters/David W Cerny)

It can, however, encourage Catholics to understand the issues at stake and be ready to stand up for beliefs and principles.

"Freedom means love and mercy, as well as engaging for the common good and caring for the weakest," Poland's Catholic primate, Archbishop Wojciech Polak of Gniezno, reminded a Nov. 11 centenary Mass, as 200,000 people joined a government-backed independence march in Warsaw. "Love of homeland calls us to respect the rule of law and respect each other, to join rather than exclude, to unite rather than divide, to accept rather than reject."

Zaryn, the historian, thinks the church will speak out more forcefully if EU pressure threatens to compromise key Christian values and undermine democratic choices.

Although the November anniversaries were dominated by British, French and German commemorations of the 1918 armistice on the Western Front, he's pleased Poland's own independence was also noted and celebrated worldwide — along with the church's historical contribution toward sustaining national identity during the long years of foreign domination.

With support still running high in Eastern Europe for parties and governments much criticized by the EU, a key test will come in January when Romania assumes the EU's rotating presidency, as well as next May when fresh elections are held for the European Parliament.

"Every state and nation has brought something unique to the EU, which should be accepted and respected — there'll be resistance if attempts are made to impose decisions by just one narrow group of leaders," Zaryn told NCR. "Now that countries like ours are expressing themselves more confidently, I hope there'll be no return to the blatant and hurtful inequalities of the past. And that we can count on our politicians to defend our interests without needing to turn to the church."

[Jonathan Luxmoore covers church news from Oxford, England, and Warsaw, Poland. The God of the Gulag is his two-volume study of communist-era martyrs, published by Gracewing in 2016.]