(Unsplash/Cel Lisboa)

Whether the issue is city councils and trans fats, fast food jobs for inner-city teens, obesity, diabetes, heart attacks or the fear many have that they (and America) are permanently fat, what we eat matters.

What we put into our body has an impact on our bodies and much, much more.

A couple weeks ago, I revisited the concept of sacred chow — that is, a love of healthy food, disdain for agribusiness and a more thoughtful approach to what and how we eat. Here, I'd like to return to the topic once more in a way that tries to take back the table the way others have taken back the night. Sacred chow helps our bodies embody their holy and sacred intention. It doesn't keep us from dying so much as turn us toward living.

Becoming more conscious about how food gets on our plates and into our stomach is an essential first political step. Migrant workers, the soil, the pesticides themselves join packagers and truckers and boats in getting our food to our plates. Just looking at everything on any one plate as a long — and not short — experience is important.

Here are a few books to help you turn the corner toward a more sacred chow experience:

- Real Food: What to Eat and Why by Nina L. Planck (Bloomsbury, 2016) This little guide goes a long way to help you plan meals.

- Animal, Vegetable, Miracle: A Year of Food Life by Barbara Kingsolver (HarperCollins, 2007) In this book, Kingsolver teaches herself to live by eating well, adopting with her family a rural-based food life for one year.

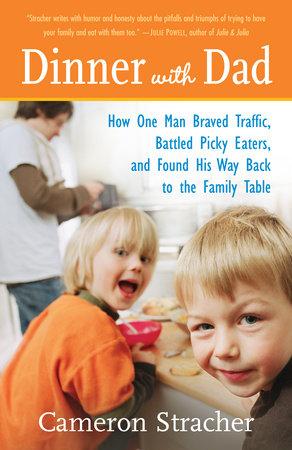

- Dinner with Dad: How I found My Way Back to the Family Table by Cameron Stracher (Random House, 2007) Eating a "family" meal can help us both be more conscious about what goes on the table and also what happens at the table.

- Life is Meals: A Food Lover's Book of Days by Kay and James Salter (Knopf, 2006) This book is a daily devotional of sorts, built around food.

- Mindless Eating: Why We Eat More Than We Think by Brian Wansink, (Bantam, 2006) When we keep a spiritual food diary, we learn to observe and cherish food.

- Cooking with the Bible: Biblical Food, Feasts and Lore by Anthony F. Chiffolo and the Rev. Rayner W. Hesse, Jr. (Greenwood, 2006) This book shows the way in which religion has always been deeply food invested.

- The United States of Arugula: How We Became a Gourmet Nation by David Camp (Broadway Books, 2006) This book with a funny title helps us see how luxury or gourmet eating takes us at least the first step toward sacred chow.

All these political and theological books can help us understand how to behave politically about food. They connect us to city councils and regulations and medical policies.

Advertisement

When I think of sacred chow, I start with the person and go to the political and make a trip back and through. I like to think of myself as somebody with two green thumbs: one grows things in a garden and makes things in a kitchen, and the other grows things in public, through policies and protests and politics.

I have several role models in the behaviors. One of them is the early 20th-century American novelist Edith Wharton, who gardened in France and wrote about it as a well-considered domesticity. She helps me connect my two hands and my two thumbs.

Another role model, albeit as a warning, is M.F.K. Fisher, who wrote about food in dozens of volumes of books and essays, but to me made the political connection weakly. She acted often as though the beauty of her table was disconnected from the money in her pocket, as well from as the beauty of French agriculture, its government's food policies and its culture of teaching about food and other public matters.

Renowned chef Alice Waters also comes to mind. In 1971, she opened in Berkeley, California, one beautiful restaurant, Chez Panisse, and refused to do a chain of them. Credited with starting the farm-to-table movement, some of Waters' philosophies on food are simply summarized: Food is precious; eat together.

(Random House)

What we really need is a new book about the politics of food that loves food the way Fisher does. It may already exist somewhat in early Christianity historian John Dominic Crossan's ideas about commensality. He says that Jesus ate with the wrong people and that's what got him in trouble. When we eat with "agribusiness," we also get in trouble; it's just a different kind than what Jesus had.

Crossan makes the most powerful argument about the spirituality of food. Politics is always at the table — with whom we eat, where we eat, how we eat. He argues that the reason for Jesus' crucifixion was that he ate with "sinners." Crossan is a part of the group of edgy Jesus scholars who rely on a very few texts to show why Jesus was unusual and not just about food.

We need people with two green thumbs, who can behave politically and personally about food at the same time. We need sacred chow.

[Donna Schaper is senior minister of Judson Memorial Church in New York City.]

Editor's note: Keep up on the latest environmental coverage, and sign up here for the weekly Eco Catholic newsletter.