Police officers in Louisville, Kentucky, move past city hall Sept. 23 to clear protesters from a plaza ahead of a 9 p.m. curfew. (CNS/Reuters/Carlos Barria)

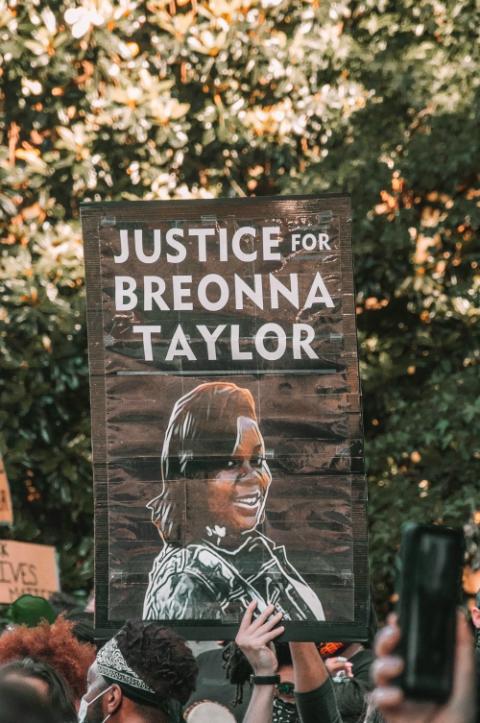

Last week's decision by a Kentucky grand jury to indict only one of three officers involved in a botched police raid that ended in the death of Breonna Taylor was, as so many things are these days, both shocking and yet unsurprising.

The shock hit me, as it did for thousands across the country, as still another plain instance of failed justice. Another person of color, this time, a young Black woman in her 20s sleeping in her own bed, killed by police without anyone found legally culpable for her murder.

The one indictment of a Louisville detective, which contained three charges of wanton endangerment for firing 10 shots through Taylor's apartment and into a neighboring residence where three other people slept, reflect charges that do not directly relate to the actual killing of Taylor. Authorities say that bullets from the gun of Brett Hankison, the indicted detective, did not strike and kill Taylor.

A Black Lives Matter protest in Atlanta (Unsplash/Maria Oswalt)

For all that is unthinkably tragic about this particular case, what is unsurprising about the course of events is not simply that no police officers are being held responsible for the loss of another Black human life, but also that the officers involved that fateful evening are protected by the law itself. Even if prosecutors in Kentucky wanted to press charges — even if only symbolically to acknowledge the need to pursue justice after the killing of an unarmed and innocent citizen in her own home — the laws, policies and civil structures already in place ensured that the police would be shielded from criminal liability.

The killing of Taylor and the subsequent failure of justice is a painful reminder that we must not be people who lose sight of the forest for the trees. This particular tree of racial injustice does not exist alone, but grew in a diseased and malfunctioning forest, reminiscent in my mind of the irradiated hellscape of the woods around Chernobyl. It is tempting to dwell on this discrete case of unaccountable criminality, but the lack of vindication for Taylor is also just a symptom of a broader systemic illness — it is one horrifying, radioactive tree that appears in hindsight to be all but inevitable considering the toxic level of structural racism and pro-police bias in the forest.

While we should absolutely memorialize Taylor and express our righteous anger through lament and protest for what is unequivocally a display of indifference to Black human life and dignity in our communities, we must also allow that energy to inform and transform our justified outrage in order to take aim at the system itself. Without structural change, sweeping legal reforms, mechanisms for genuine civilian oversight and law enforcement accountability, tragedies like this will only continue.

Although implicit bias and the consequences of systemic racism certainly play a key role in the persistence of police shootings of unarmed Black people, a major obstacle to justice after the fact remains the laws and policies currently on the books. These are often negotiated by powerful police unions, which protect those who have committed what, for civilians in comparable situations, are otherwise recognized as crimes.

As Benjamin Sachs, a Harvard University law professor, told The New Yorker earlier this year, the power and influence of police unions in bargaining on "matters of discipline, especially related to the use of force, has insulated police officers from accountability, and that predictably can increase the problem."

Among the most significant protections for police officers who kill civilians in the course of their duty is known as "qualified immunity." According to the 2009 U.S. Supreme Court decision Pearson v. Callahan, "Qualified immunity balances two important interests — the need to hold public officials accountable when they exercise power irresponsibly and the need to shield officials from harassment, distraction, and liability when they perform their duties reasonably."

In effect, the application of the doctrine of qualified immunity has done little to address the first aim of holding public officials accountable. On the contrary, as study after study has shown, such legal shielding has only increased what journalist Steven Greenhouse has described as "a sense of impunity" among police officers.

This system of double standard justice or legalized impunity reminds me of another case of widespread systemic injustice: the cover-up of clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church.

While certainly not identical cases, there are striking similarities between the egregious cover-up of horrifying acts of sexual, psychological and spiritual abuse of children and vulnerable adults perpetuated by clergy and religious in the church and the systemic protection of police officers who kill men, women and children of color.

Advertisement

In the case of the church, the systemic injustice is accounted for, in part, by a culture of clericalism. This distorted worldview maintains an uncritical view of clergy as above reproach or even error, on account of their status as ordained ministers in the church. Bishops and religious superiors sought for decades to protect this perception and the social and ecclesial benefits such an identity bestowed on the clergy. They covered over the tragic reality of sin and crime, shielded accused priests from accountability, and even attempted to discredit accusers.

In many ways, the criminal laws and institutional policies that maintain doctrines like qualified immunity provide something of a civil equivalent to the culture of clericalism in the church.

Like priests who are always already part of the broader baptized community of the faithful but often behave according to a sense of clerical exceptionalism, police are still citizens of their local communities but often act and are treated as if they are above the law.

Like priests who are ordained with a sacred responsibility to serve their fellow Christians but instead often put themselves first, police are entrusted with a solemn duty to "serve and protect" the community, as widespread law enforcement slogan states, but often ultimately serve and protect themselves and each other in the wake of misconduct.

Like priests who benefit from a large and powerful institution, police have been and continue to be protected by a system of power and authority that treats them as a category unto themselves, encouraging an attitude of entitlement, reinforcing a distorted sense of individual power, and covering over their sinful and criminal behavior with impunity.

Because of these unjust systems, neither police officers nor priests, regardless of how awful their crimes, have been uniformly subject to the ordinary rules and means of accountability that apply to all others in the community or church. Inevitably, a sense of entitlement grows in both populations and a failure of justice persists in church and state.

As with the atrocious cases of abuse in the church, the unspeakable slaughter of Black people at the hands of police rightfully elicits our deepest rage and righteous anger. But until the laws change and the policies that maintain unaccountability are replaced, justice will never be served. Grand juries will be forced to replicate the decision in Kentucky, unable to even feign redress because police-protecting statutes will tie their hands again and again.

Justice for Taylor was foreclosed from the beginning for this very reason. But the tragedy of her senseless and preventable murder does not have to go unaddressed, nor our righteous indignation and protests be in vain. The hope of justice begins with the ache of our hearts in the face of such atrocities, but it flourishes when we allow that pain to motivate our work for structural and legal reform.

[Daniel P. Horan is the Duns Scotus Chair of Spirituality at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, where he teaches systematic theology and spirituality. His recent book is Catholicity and Emerging Personhood: A Contemporary Theological Anthropology. Follow him on Twitter: @DanHoranOFM.]

Editor's note: Don't miss out. Sign up to receive an email notice every time a new Faith Seeking Understanding column is published.