Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle at Homeboy Industries. Each year, the program he founded serves nearly 10,000 people in Los Angeles, offering a sanctuary of support and a pathway to a better life for formerly incarcerated and gang-involved individuals. (Courtesy of Paul Steinbroner)

On a warm April afternoon Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle was directing a spiritual retreat at a Jesuit retreat house in San Jose, California. He was with some of his "homies," men and women former gang members who have dropped everything to join Homeboy Industries, the largest gang intervention, rehabilitation and re-entry program in the world.

Then, out of nowhere, Boyle received a text message purporting to be from a White House official. "Please expect a phone call," it said.

Shortly after, the Jesuit received news he could never have imagined. Boyle had been called to come to the White House for a May 3 event, to be one of 19 Americans awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Joe Biden.

"I have a light grasp on all these things, because you don't want to cling to anything," Boyle told NCR, in his first interview with a news outlet after receiving the prestigious award. "I thought, 'Well, that's nice, I like Joe Biden.' "

Boyle's journey began in Los Angeles, where he was born and raised. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1972 and was ordained a Catholic priest in 1984. Following the 1992 Los Angeles riots, Boyle launched Homeboy's first social enterprise, Homeboy Bakery, in an abandoned bakery across the street from Dolores Mission Church in Boyle Heights, one of the city's most dangerous and disadvantaged neighborhoods at the time.

Advertisement

Each year, Homeboy Industries serves nearly 10,000 people in Los Angeles, offering a sanctuary of support and a pathway to a better life for formerly incarcerated and gang-involved individuals.

Homeboy boasts 13 social enterprises, each providing job training and purposeful work. The organization's holistic services include tattoo removal, legal aid, education, housing support, substance use disorder treatment, and mental health services.

Every aspect of Homeboy's work is trauma-informed, offering Californian ex-gang-members a therapeutic community that fosters whole-person physical and spiritual healing.

"I still haven't responded to all my text messages or all my emails, so I'm chipping away little by little," Boyle said about the experience of receiving the honor. "I don't really think about things like legacy or accomplishment or success. I think one just puts one foot in front of the next, and does the best they can, and try to let love live through you. All those things are hard to do, but one can try to do the best they can."

Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle and some of his trainees participate in a 5k race at Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles in 2020. (Courtesy of Paul Steinbroner)

Boyle spoke after returning from a trip to Belfast, Northern Ireland, where he's helping support one of Homeboy's partner programs called the Turnaround Project. The Belfast program is part of the Global Homeboy Network, an organization that has 300 partners in the U.S. and 50 abroad. The purpose of this international coalition is to support citizens coming out of prison to create social enterprises.

Next, Boyle traveled to New Zealand, where he gave a talk to the local Anglican Synod of Bishops.

While Boyle was receiving the Medal of Freedom in Washington, D.C. accompanied by only eight close friends and relatives, his community of ex-gang-members at Homeboy in Los Angeles was following the live broadcast through large screens set up for the occasion.

Among them was Pamela Herrera, 39, the general manager of Homegirl Cafe, a service offered by Homeboy where ex-gang-members like Herrera have been fully employed.

"I'd been in my drug addiction for 12 years. I started at age 14, and by when I was 15, I was out in the street and ended up in juvenile hall. My grandpa used to call me a 'lost soul, the lost soul of Los Angeles,' " said Herrera, who encountered Homeboy in 2011.

Herrera said she arrived at Homeboy hopelessly when a job she was about to be offered as a manager at a McDonald's franchisee was rescinded after they ran a background check on her. She remembered arriving at Homeboy, and being greeted by other trainees who took her to Boyle's office, where she sat down to wait for him for a few minutes.

When Boyle came in and saw her, he asked her, "What could you do for me?"

Herrera replied, "I want to change my life. I'm tired of living the lifestyle I lived."

She entered the program and started off as a hostess at Homegirl Cafe. She worked her way up, becoming an executive assistant, and then a business manager of the merchandise store. She became general manager of Homegirl Cafe in 2021.

"My grandfather passed away knowing that I was not anymore a lost soul, that I was found and that I was doing good," said Herrera, adding that one of the greatest joys of her life was seeing Boyle officiate at her grandfather's funeral.

"The Medal of Freedom to Father G. is such an honor, it fills my heart and makes me feel part of something bigger than us. I'm just so proud of him," she said.

Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle speaks at an event at Homeboy Industries. (Courtesy of Paul Steinbroner)

According to Boyle, the most challenging years for Homeboy were the first 10, up to the early 2000s, when the violence of gang fighting in Los Angeles was at its peak.

"Gang members were demonized enough that we were painted with the same brush, saying that we were somehow 'fraternizing with the enemy,' " said Boyle. "But I think people started to see that this approach really is effective. This city has embraced Homeboy, which is really heartening now."

"I think people who insist on being tough on crime are people who aren't serious about reducing crime," said the priest. "Homeboy reminds society of that, and we provided an exit ramp for gang members who didn't imagine any way out of this darkness. We provided the kind of a way to do it."

As a matter of fact, the city of Los Angeles has also just proclaimed a "Father Greg Boyle Day," which will be celebrated annually on May 19 in honor of Boyle and Homeboy.

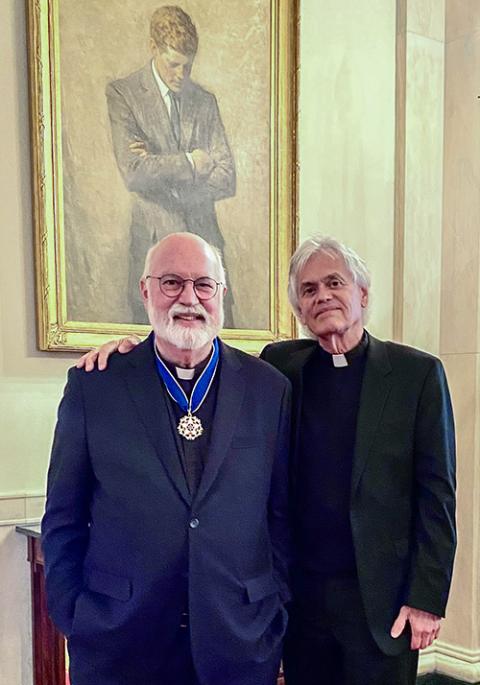

Jesuit Frs. Greg Boyle and Mark Torres pose for a photo at the White House after the Presidential Medal of Freedom ceremony on May 3. (Courtesy of Mark Torres)

Jesuit Fr. Mark Torres, who joined Homeboy as a therapist in 2002 and has since worked more broadly in spirituality, mindfulness and mental health areas for former gang members, was one of Boyle's eight guests at the White House Medal of Freedom Ceremony.

"When Greg began Homeboy, he was not well received," Torres told NCR. "They said he was 'coddling' gang members, but little by little that feeling towards criminals and gang members shifted over time. I think in psychology and sociology we're more trauma-informed, we're more and more aware medically that there's neurological evidence that shows that the brain is actually negatively impacted by violence and trauma, neglect, abandonment."

With Torres' input, Homeboy's trainees engage in activities to get to know and forgive each other. Members come from different gangs in Los Angeles, but they all know that once they cross the doors of Homeboy Industries, they enter neutral territory, where there is no room for conflict.

"When they sit together, they often end up in tears, knowing that all the people around the same table have had traumatic and painful lives, where there's been neglect, abuse, trauma and violence," said Torres. "When hearing they're not alone, it takes away that loneliness. It builds community, it builds a sense of kinship. Kinship is a word Greg uses a lot."

Torres explained that the Homeboy system has grown organically over time, adapting over the years based on the needs of the ex-gang-members. One of the emergencies Boyle sensed early on was that of employment, but almost no trainee had the social and human skills to get started.

Another detail that Boyle could not imagine could be influential in the job search for his "homies" was the fact that most of them arrive at Homeboy covered in tattoos, often even on visible parts of the body such as the arms, hands, neck, and forehead.

Dr. Troy Clarke removes a tattoo of a former gang member at Homeboy Industries. (Courtesy of Troy Clarke)

For this reason, Homeboy now also offers its trainees a free service to remove their tattoos, to be more competitive and fit for the job market. Troy Clarke is a medical doctor from Boston who for the past 15 years has spent about 10 days a month at Homeboy in Los Angeles removing former gang members' tattoos with cutting-edge laser techniques.

"Tattoos are for them permanent reminders of the past, and in order for people to move forward with their lives, they can't have the remnants leftover," Clarke told NCR. "You need to clear it completely off. That's the physical part, then the spiritual and the mental parts will take time."

"Every tattoo has a meaning for these individuals. For some of them, they chose to put them on. For others, they were forced to put them on out of torture. For pretty much all the patients that come in, it's so much more painful to have those tattoos on than to remove them," Clarke said.

"When a person comes in, it's cathartic," he said. "You're peeling back layers of memories, when people come in. They know they can move forward in their lives."

Paul Steinbroner, a documentarist who has produced more than 50 films about addiction and medical education throughout his career, said Boyle is like a father to most of the trainees at Homeboy. When Steinbroner visited Homeboy for multiple weeks in 2020 to shoot the documentary "Homeboy Joy Ride," he was amazed beyond belief at the degree of "tenderness" with which Boyle enters the lives of the trainees.

"If you're a gang member, you need eyes in the back of your head, because somebody's always going to do you wrong," Steinbroner told NCR. "You trust no one. Father Greg reestablishes them as children of God. He allows them to rediscover who they are. He's like a mirror for reflecting back on who they could become."

Jesuit Fr. Greg Boyle is seen with some of his trainees during a 5k race at Homeboy Industries in Los Angeles in 2020. (Courtesy of Paul Steinbroner)

Looking forward to the future, Boyle said Homeboy wants to expand its campus footprint and that they are reimagining alternatives to incarceration. As part of this vision, Homeboy Industries has initiated "Hope Village," a project dedicated to addressing issues such as gang-related addiction and mental health, while also providing housing, social services, and art.

These initiatives could contribute to reducing prison populations, said Boyle, mentioning also that he is writing his new book, which is set for publication in October and which will offer commentary on current social national and global issues.

Boyle said that without the value of tenderness at the core of its mission, Homeboy Industries could not function. He said he does not intend to change the world, or policies on crime management, but simply to offer redemption and an alternative vision of life for ex-gang-members.

"If they've surrendered to all the dosing of tenderness here, then they will be sturdy and resilient once they leave, and they will know the power of the courage of their own tenderness," said the Jesuit.

"It's not so much, 'Will the world change or be different out there?' " he said. "It's about people seeing things with a different lens. The world doesn't have to change, but the way they see it will change. That means they're not going to be toppled by the difficulties that would normally lay them low."