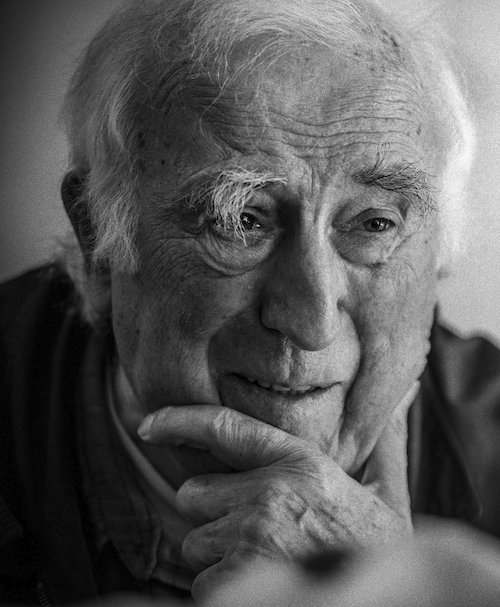

Jean Vanier in the documentary "Summer in the Forest"(CNS/Abramorama)

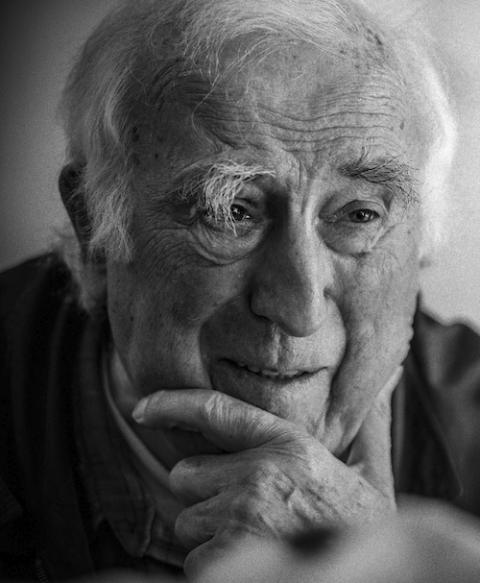

Jean Vanier in the documentary "Summer in the Forest"(CNS/Abramorama)

Since the news broke Saturday morning that Jean Vanier had coercive, nonconsensual and abusive sexual encounters with at least six adult women, my social media feeds have been filled with folks trying to make sense of these revelations.

I admit that Vanier was not someone I looked to for spiritual inspiration. Though he was not a priest, my years of experiencing the clericalism of both the clergy and the laity had made me weary and wary of the Catholic tendency towards hero worship, particularly of grand older men.

The fact that I did not have an emotional tie to Vanier may have helped me take an unflinching look at L'Arche's 10 page report on the abuses that he and his mentor, Dominican Fr. Thomas Philippe, perpetrated against vulnerable women.

L'Arche should be commended for its support of Vanier's victims and for its fearless transparency about its founder's misconduct. Tina Bovermann, national leader/executive director of L'Arche USA, has modeled for all church leaders how to deal with abuse with integrity and compassion.

"I just want to be very clear that we stand on the side of these women who have been harmed," Bovermann told NCR this weekend. "We want to validate these people who have been harmed," she said, and "condemn" the behavior of Vanier.

The details of both Philippe's and Vanier's abuses are troubling and sordid. But what struck me most after reading the report was the cultic nature both of the abuse and Philippe's relationship with Vanier.

In 1946, Philippe created l'Eau Vive as a "school of wisdom" and a program of initiation into contemplative life. Vanier arrived there in 1950 and, it seems, quickly fell under Philippe's spell.

When Vanier was questioned in 2009 about Philippe, he said, "It was obvious to him that I was his spiritual son who would do anything to support him in his plans," according to L'Arche's report.

Advertisement

Vanier was questioned about Philippe because it had come to light that his spiritual father had been sexually abusing women from the earliest days of l'Eau Vive, to the point that, in 1956, the Holy Office (now the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith) barred him from any public or private ministry, including celebration of the sacraments, spiritual direction and preaching.

The fact that women in the early 1950s found the courage to speak out against a charismatic priest and the fact the Holy Office responded to their claims by putting him on trial and condemning him so severely suggests how grotesquely abusive Philippe's actions were.

But equally grotesque is how Vanier remained devoted to Philippe, even though, as early as 1952, he was made aware of his assaults on women. As late as 2016, Vanier denied have any knowledge of Philippe's abuse.

Vanier's lies are made all the worse by the revelation that he even procured women for Philippe in the years after he was removed from ministry. According to L'Arche's report:

Against the advice of the Church, between 1952 and 1964, Father Thomas Philippe and Jean Vanier maintained a deep bond. Letters from this period reveal the extent of Father Thomas Philippe's influence on Vanier's thinking and behavior. They also report on the visits Jean Vanier made to him and how he helped him meet clandestinely with the women of l'Eau Vive.

In one particularly disturbing section of the report, a letter is quoted that shows Phillippe offering advice to Vanier — using allusions to a story in John's Gospel — about how to take sexual advantage of particular women:

For XX be very careful. You can sometimes pray with her, if it is very prudent; but externally the minimum, no more than St John at the Last Supper and in a rather discreet way. I feel that the Blessed Virgin asks us to be very careful about this point.

Both Phillippe and Vanier used allusions to Marian theology and the Scriptures to justify their sexual abuse of women.

One of Philippe's victims said the priest claimed "he was an instrument of God, and therefore at present and directly moved by God," and that sex with him conferred " 'special graces' that no one could understand."

One of Vanier's victims said "the spiritual accompaniment transformed into sexual touching. I told him I had a lover, he said that it was important to distinguish (what happened between us) referring to the Song of Solomon."

Another victim claims the Vanier rationalized his sexual coercion by claiming: "This is not us, this is Mary and Jesus. You are chosen, you are special, this is secret."

Philippe, it seems fair to say, functioned like a cult leader, and Vanier was not only brainwashed by him, but enabled and replicated his perverse actions. Sadly, their ritualized abuse of these women is all too common among charismatic personalities.

In a 2018 essay, Alexandra Stein, an expert on cults and extremist groups, wrote about the ways in which cult leaders often groom women for sexual encounters.

"This type of sexual abuse is often sold as way to become closer to the spirits or to gods; it's represented to adherents as not really 'sex' at all, but a form of spiritual practice," Stein wrote.

But unlike in a cult, Philippe and Vanier had centuries of Catholic doctrine to buttress their behavior.

The Vanier case reaffirms an argument I have made in this column before, which is that the church's radically patriarchal leadership structure and theology are at the root of most sex abuse cases in the church.

Patriarchy is any system in which men hold the power and women are largely excluded from it. In a patriarchal structure, powerful men dominate women, children and other vulnerable men.

In nearly every case of sexual abuse we have heard about in the church over the years — whether the situation is priests abusing children, or bishops raping nuns, or ex-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick sexually coercing seminarians, or Philippe and Vanier sexually assaulting adult women — there is one common denominator: the patriarchal belief that a special class of spiritual men are entitled to use women, children and other vulnerable men for their sexual gratification.

When this patriarchal system is combined with the theological notion of gender complementarity, which states that God calls men to lead and women to submit, it creates the perfect breeding ground for kinds of abuse we see in the Vanier case.

As I watched people grapple with this dark side of Vanier, I saw more than one person suggest that Vanier was like all of us, a mix of good and evil. That sentiment, I think, must be rejected. Most of us do not act the way Vanier did, abusing his spiritual power, twisting theology to force women into ritualistic sexual abuse, and lying to protect himself and his nefarious spiritual father.

What we should do instead is contemplate the mystery of how such an extraordinary movement like L'Arche could grow out of such unscrupulous and, frankly, creepy beginnings.

Perhaps this moment invites us to be careful of over-identifying charismatic leaders with the movements they create. If L'Arche is as good and holy as many say it is, it is because of the courage of leaders like Tina Bovermann and the goodness and holiness of the countless lay people who built the 154 L'Arche communities in 38 countries.

Though they may have been inspired by the words and witness of Jean Vanier, what has truly given their movement life is the God who reaches out to them in the lives of the marginalized people they serve and the Spirit who dwells within the communities they have created among themselves. As they work through their grief, may they continue to be a source of strength and new life for one another.

[Jamie L. Manson is an award-winning columnist at the National Catholic Reporter. Follow her on Twitter @jamielmanson.]

Editor's note: We can send you an email alert every time Jamie Manson's Grace on the Margins is posted to NCRonline.org. Sign up here.