Ixil Indigenous Jacinta Ceto, survivor of the Guatemalan civil war, attends the hearing against retired Gen. Benedicto Lucas García at a court in Guatemala City on April 8. A Guatemalan court began a trial against Lucas, 91, already convicted of crimes against humanity, for the massacre of more than 1,200 Indigenous Ixil Maya people between 1978 and 1982, a period when his brother Romeo Lucas García was in power. (AFP via Getty Images/Johan Ordonez)

Women in bright red native dress testified for hours to brutal murders of loved ones as a landmark trial began here against former Gen. Manuel Benedicto Lucas García, architect of a counterinsurgency campaign in a war where some 200,000 persons, mostly unarmed Maya, were killed or forcibly disappeared in the 1980s.

The case against Lucas has arrived in court due to the efforts of the Santiago de Guatemala Archdiocese.

"I heard them crying out — my mother crying out," said Maria Torres, now 75. Torres said she hid in 1981 when soldiers entered the family house at dawn, raped her mother and slayed her siblings, whom she named slowly at the prosecutor's request.

Sitting before three judges protected by a shield that gave them a hazy look, and a larger-than-life wall projection of Lucas, who was participating from another location, the witness's shoulders began to shake. The men tied up her father, a member of Catholic Action, she said, then knifed him in the throat.

The charge against the 91-year-old Lucas — genocide — makes this one of the most important judicial events in the country's history. The plaintiffs, the archdiocese's Human Rights Office and a victims' rights group, the Association for Justice and Accountability, say that Lucas was criminally responsible for a project to eliminate part of the Maya people in the western highland region known as the Ixil Triangle.

Photos of persons who were forcibly disappeared hang in front of the Supreme Court building in Guatemala City Nov. 25, 2019, during a genocide case hearing involving three army commanders, including former Gen. Manuel Benedicto Lucas García, accused of steering the military campaign against the Ixil Maya communities between 1978 and 1982 during the country's civil war. (AP Photo/Moises Castillo)

In the small courtroom where the trial began April 5, archdiocesan lawyers sit at a long table alongside attorneys of the Public Ministry, which has brought the government's case after years of research by the church and the victims' group.

Genocide trials are rare anywhere in the world. In this country where a pro-democracy government has been in place only since January and remains under threat from ultra-right opponents in the judicial system, business and ex-military communities, the trial is a leap of faith.

'One of the bloodiest generals'

"The law says a crime was committed," said agricultural worker Diego Velasco, who was age 14 when he said soldiers fell upon his mother, María, father Antonio, and his siblings Nicolás, 25, and sister Manuela, 7, as they cleaned the family cornfield.

The soldiers tied everyone's hands, said Velasco, but when they ordered his father to give them his plastic boots, he refused, because he said he had "paid for them." He would not be humiliated by going in bare feet.

"They shot my father in front of me," Velasco said, repeating "in front of me" and pointing to his forehead and the side of his head where bullets entered.

In a house about 15 minutes' walk from the cornfield, troops abused two women and beat Velasco's brother Nicolás, he testified. Gathered with other minors, Diego Velasco managed to run and hide nearby.

Later, he said, he found Nicolás' body with bullet wounds, and Manuela's remains. María, his mother, was never found.

Lucas was "one of the bloodiest generals known to Latin American history," said archdiocesan Human Rights Office director Nery Rodenas, who announced the trial's launch at a press conference on March 24.

Mario Trejo Millián, the office's lead attorney for the Ixil case, said in an interview that he believed there was "no question" that the genocide charge would be proven, despite the high bar that requires proving motive and intentionality — that Lucas with his army deliberately sought to wipe out the Ixil Maya communities.

Advertisement

Witnesses have testified that neither they nor their murdered family members were guerrillas nor had they come into contact with guerrillas in their communities or fields. The army, said Trejo, aimed to "eliminate" the people in the Ixil geographic area because it considered them "the internal enemy."

The archdiocese is taking a major part in the trial because "the church has always supported the victims," said Trejo.

According to a U.N.-backed Truth Commission, reported acts of violence by the guerrillas in the 36-year war (1960-96) represent 3% of the violations registered, while 93% were committed by agents of the state.

In 1981, President Romeo Lucas García named his brother Benedicto army chief of the General Staff in response to the growing threat of insurgency to the military regime. (In 2018, Benedicto Lucas was convicted along with four other Guatemalan ex-officials to 58 years in prison for crimes against humanity and aggravated sexual assault of a woman activist critical of the army, and the forced disappearance of her 14 year-old brother.)

In the genocide trial, Lucas is participating from a hospital where he has had surgery, wearing a white robe, arms often folded across his chest, his face expressionless. One defense lawyer is at his side; others are in the courtroom.

Civil patrols

Lucas created "self-defense" patrols to help carry out his strategy, eight to 20 local men in a patrol. "I founded the self-defense patrols because it was necessary," Lucas once told me in an interview. The guerrillas, he claimed, were "destroying houses to the ground."

During the trial, witnesses have testified that it was soldiers who burned their houses to ash.

Lucas was known for flying in by helicopter to towns and villages in the heat of the war and talking to residents who had been summoned to a central field or plaza, beginning his discourse with a disarming salutation and ending with an unmistakable threat of violence unless presumed support for guerrillas stopped. Those who didn't join his civil patrols were assumed to be rebels or supporters.

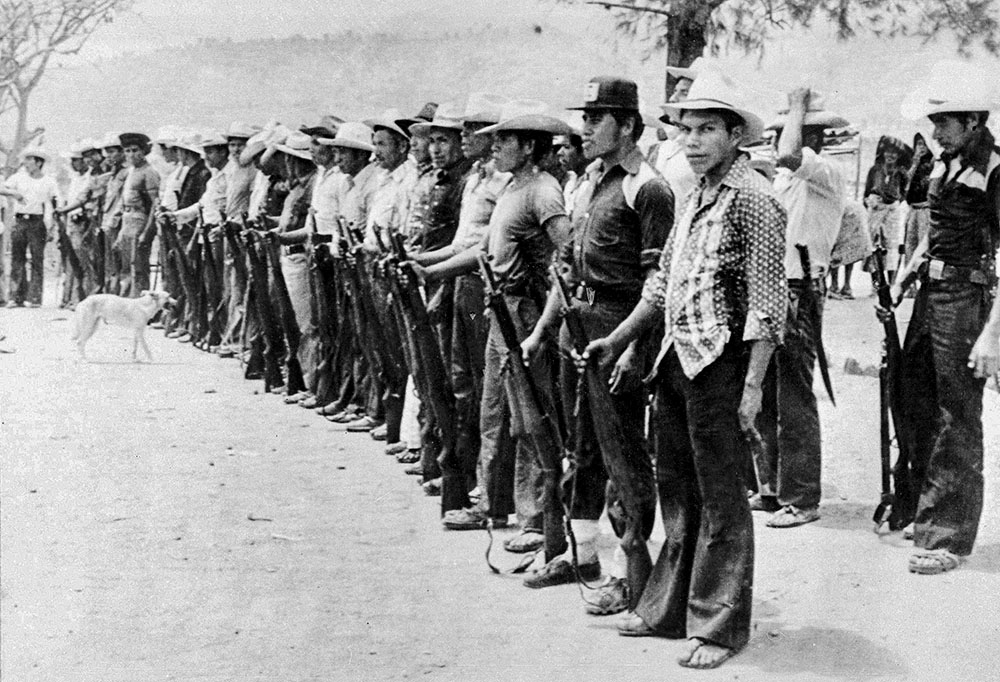

Civil patrol members of the Rabinal Department of Baja Verapaz in the north of Guatemala are seen carrying U.S.-made M-1 rifles March 6, 1982. (AP)

The insurgent Guerrilla Army of the Poor sometimes used hit-and-run tactics when government troops appeared, but the rebels did not have the military capacity to resist the much larger and better equipped army, or to protect the population from brutal army offensives once Lucas' counterinsurgency reached full force.

It was common to encounter the civil defense patrols in the highlands in the 1980s. Sometimes they carried only sticks, sometimes ancient-looking bolt-action M-1 rifles. They blocked entrances to villages, sat in elevated watchtowers or in roadside shelters without walls, only permitting a reporter to pass after noting identification documents or sending a runner to get permission from a higher authority. They were sometimes boys or elderly men, sometimes in ragged clothing, often looking tired. They might serve around the clock, losing work in their fields, or hiring someone to work for them from their scarce funds while they took their shifts.

Guatemala's Catholic bishops and human rights groups denounced the forced patrols, to no avail.

In a report from testimonies collected by the Human Rights Office's Inter-diocesan Project of Recovery of Historical Memory (1998), civil patrols were deemed responsible in one out of five of the war's massacres. (Bishop Juan Gerardi, after whom the archdiocesan rights office is now named, was murdered two days after he presented the report in the cathedral.) Eventually, the patrols grew to become the largest militia in Latin America, with some 1.3 million members in 1984.

The French connection

When I interviewed Lucas for several hours in 1993 in the jungle town of Poptun where he was mayor, he was fit and burly and proud of his creation of the civil patrols. As a young man he studied at the famed French military academy St. Cyr, and later at the U.S. School of the Americas, renamed in 2001 the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation.

Retired Gen. Benedicto Lucas García is seen on a screen during a video call from the ward of a military hospital where he is being held during his trial at a court in Guatemala City on April 5. (AFP via Getty Images/Johan Ordonez)

In the interview, it became clear that the bloody French struggle to hold on to its Algerian colony had permeated Lucas' days at St. Cyr. His instructors went back and forth from the classroom to the field in North Africa, where "the situation was very chaotic, it was a question of seeing who would survive."

He absorbed what his instructors considered the existential nature of the North Africa campaign: It was obligatory to fight in defense by any means necessary; the future and image of France depended upon it.

At St. Cyr, he said, "logically the training revolved around guerrilla warfare — it was no longer about the war of world powers, but rather guerrilla war with improvised tactical situations, agile responses."

At the time, France was still reeling from its final defeat in Indochina, in 1954 at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam. This, too, Lucas appeared to take as a lesson. Some French officers, he said, blamed their loss on U.S. failure to come to their aid; the United States was an undependable ally. The battle against insurgency must operate in its own way.

In 1988, Amílcar Méndez, now 75, founded a rights group that supported civilians who wanted to leave Lucas' patrols and the tactics learned at St. Cyr and elsewhere. Lucas García, Méndez said, went into the countryside with troops in a manner "irrational, cruel and inhuman."

Now, with the genocide trial, there are "great expectations for justice, but whether or not it will come we do not know," he said.