People are seen at an early voting site in Fairfax, Va., Sept. 18, 2020. (CNS/Reuters/Al Drago)

There's been a lot of discussion about the role of religion in the current presidential election, with pundits prognosticating whether President Donald Trump can still count on 80% of white evangelicals to vote for him as they did in 2016, or whether Joe Biden, an old-school Northeastern white Catholic, can erode his fellow religionists' support for Trump, whom they backed by a 20 point margin over Hillary Clinton.

However, the most important religious group to the 2020 presidential election is not really a religious group at all.

When asked to state their religious preference on a survey, a growing share of Americans shy away from picking a specific flavor of Christianity, and don't affiliate with other, smaller religious groups like Hindus or Mormons. They are also uncomfortable describing their views as atheist or agnostic.

Instead, when they are faced with a question about religious preference by a pollster, they check the box next to the words, "nothing in particular."

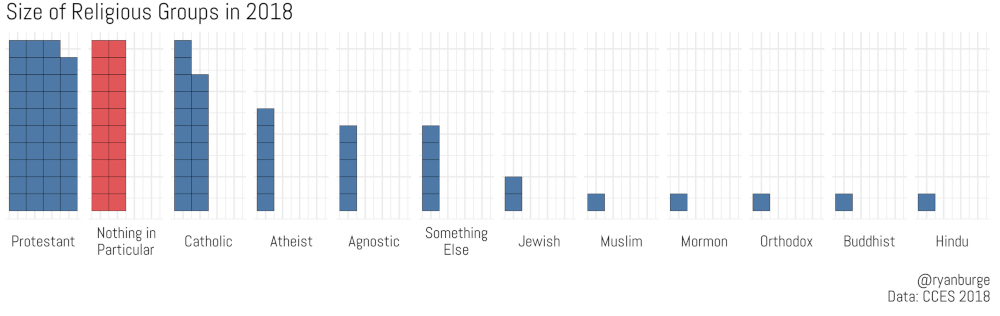

Size of Religious Groups in 2018. (Graphic by Ryan Burge)

These are part of, but not identical to, the famous religious "nones," who now account for some quarter of Americans. That larger group includes the nothing in particulars, but also atheists and agnostics.

The nothing in particulars, however, out-none their fellow nones. They are the statistical equivalent of a shrug of the shoulders.

When Barack Obama was elected president in 2008, nothing in particulars were about 15% of the general population. A little more than a decade later, that share has jumped to 1 in 5 adults, or about 20%.

To put that in context, nothing in particulars are statistically the same size as evangelical Protestants or Roman Catholics. For every atheist on a survey, there are 4 nothing in particulars. For every Mormon, there are 20.

For this reason alone, they should be considered in their own category. But there's more: While 44% of atheists have a four-year college degree, just 20% of nothing in particulars do — the lowest of any religious group in the United States today.

Atheists are twice as likely to make more than $100,000 per year as those in the nothing in particular category. And based on measures like attending a protest, working on a campaign or putting up a yard sign, nothing in particulars were half as likely to be politically active compared with atheists.

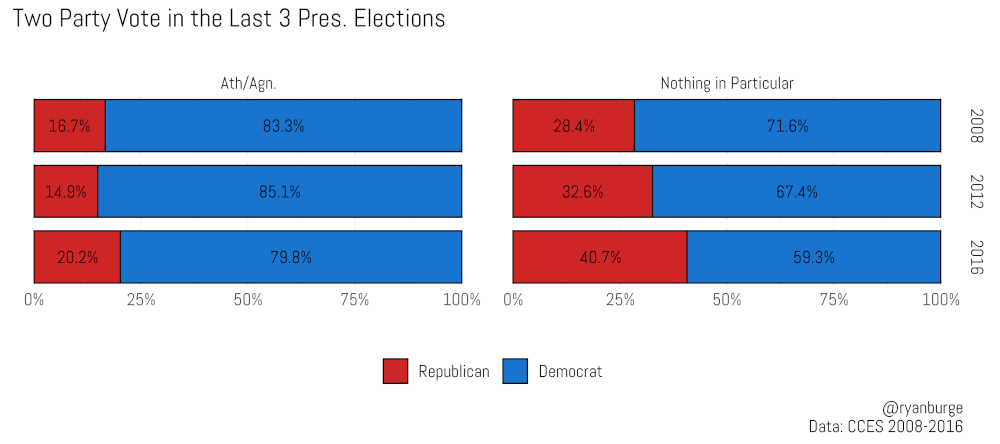

Two Party Vote in the Last 3 Presidential Elections. (Graphic by Ryan Burge)

For those who track the electoral behavior of the largest faith-based voting blocs (white Protestants and Catholics), stability has been the theme. Voters in those camps have shifted just 2 to 3 percentage points toward the GOP since 2008. The nothing in particulars' allegiances, however, have shifted dramatically in the last decade.

The Democratic Party used to be able to rely on receiving a huge share of the nothing in particular vote. Obama won this group by 43 points in 2008. That slipped to 35 points in his reelection bid in 2012, and the slide accelerated when Hillary Clinton was the nominee. Clinton earned 60% of their votes in 2016, while Trump garnered nearly 40%.

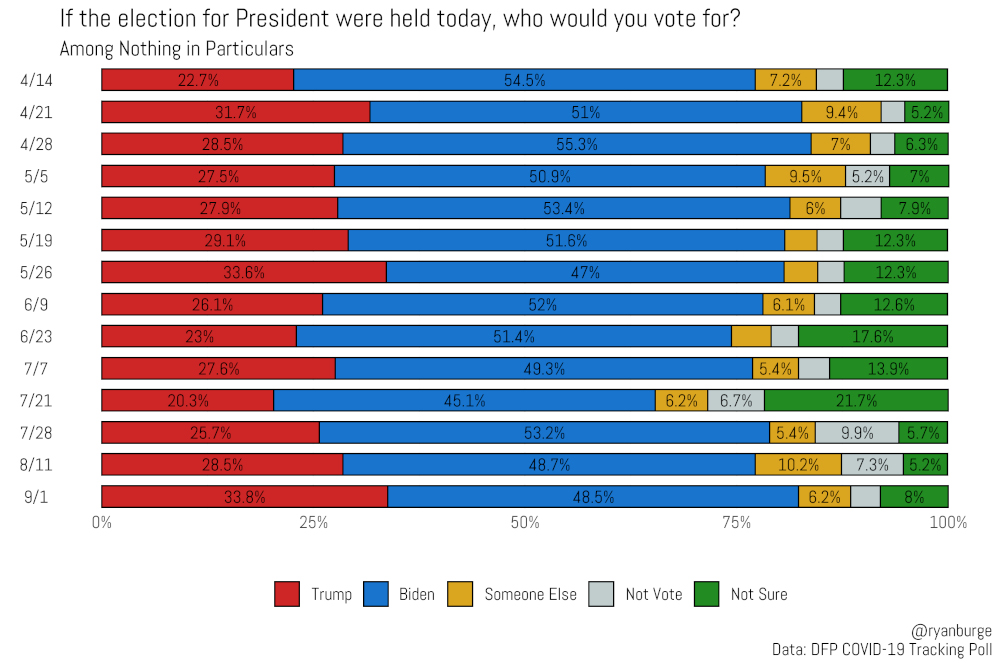

In a poll conducted Sept. 1 by Data for Progress, 38.7% of the nothing in particulars indicated that they would vote for Trump in 2020, in line with his 2016 results. Biden's share among this group was 48.5%, a double-digit decline from even Clinton's slackened performance. Biden would need to win over every undecided nothing in particular, as well as pick up a few third-party voters, to get back to the results of just four years ago.

Given their low levels of education, the nothing in particulars live a life of economic precarity. In 2018, they were 30% more likely to have lost their job than the general population. It stands to reason that large shares of nothing in particulars worked in jobs that were deemed essential during the height of the pandemic.

If the election for President were held today, who would you vote for? (Graphic by Ryan Burge)

The silver lining for Democrats is that, despite the fact that many members of this group had to risk exposure to the coronavirus to keep their jobs, few nothing in particulars said they have followed public affairs closely in the last few months. While 45% of Americans say that they were following public affairs "most of the time" in the spring of 2020, just a third of nothing in particulars answered the same way.

If 2018 is any guide, nothing in particulars are not going to be volunteering for campaigns or even putting up political yard signs in the run-up to Nov. 3. It may be reasonable to assume that their voting record is not robust.

As with everything else in our current culture, the internet may change this, as the web seems to provide the ideal avenue for candidates to reach out to this crucial but disengaged bloc.

While many nothing in particulars say they are not paying attention to public affairs, significant numbers report that they have posted or commented on political stories on social media. Six in 10 said that they had read or watched a political story on Facebook, Twitter or YouTube before the midterm elections in 2018.

Instead of focusing on the widening "God gap" between the religiously devout Republicans and the increasingly secularizing Democrats, persuading nothing in particulars — by aiming toward those internet platforms — may not just be the key to the 2020 election, but for electoral politics at the federal, state and local levels for the next several decades.

[Ryan Burge is an assistant professor of political science at Eastern Illinois University and a pastor in the American Baptist Church. He can be reached on Twitter at @ryanburge. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.]

Advertisement