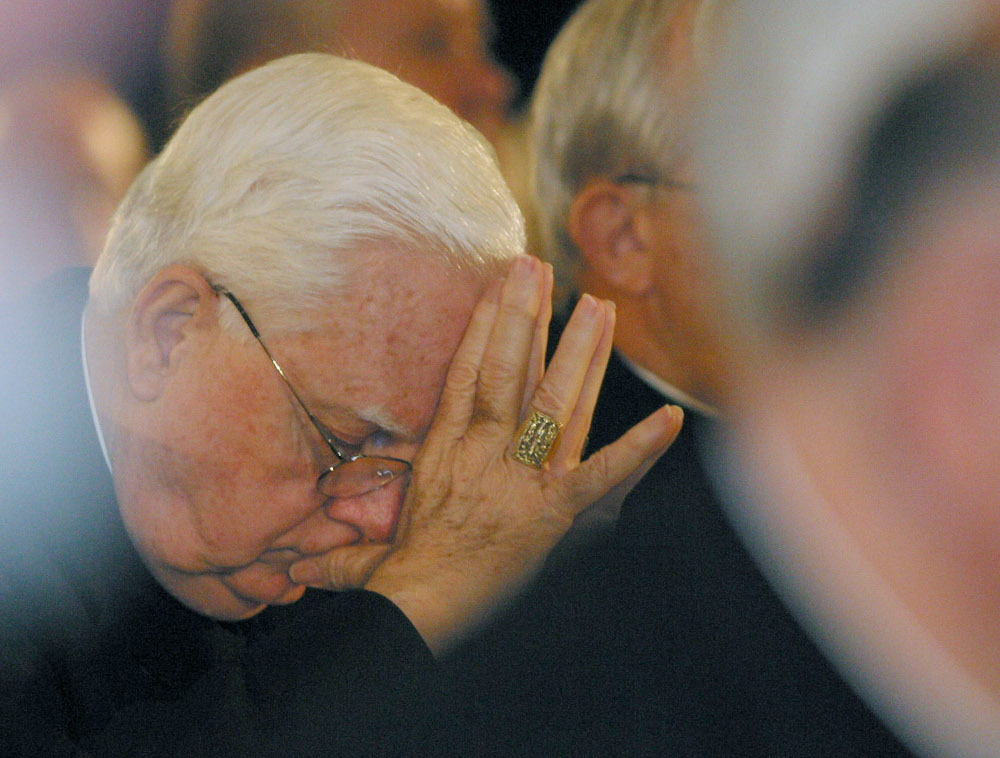

Boston Cardinal Bernard Law bows his head as a victim of clergy sexual abuse begins to address the U.S. bishops in 2002 in Dallas. (CNS/Bob Roller)

Public awareness of sexual abuse by Catholic clergy actually dates from 1984. It was triggered by the public exposure of widespread sexual violation of children by a single priest in the Diocese of Lafayette, Louisiana, and its systemic cover-up by the church's leadership that lasted well over a decade.

Cardinal Bernard Law, who went from in 1974 being bishop of Springfield-Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to in 1984 being named archbishop of Boston, became the most powerful and influential Catholic bishop in the United States. This all came to a screeching halt in 2002. In one day Law became the face of hierarchical treachery and dishonesty when The Boston Globe revealed the systemic cover-up of widespread sexual abuse by Boston priests, most of it his doing. He remained the face of the hierarchy's disgraceful attitude towards the violation of minors and the vulnerable. Even in death he remains the focal point of the anger and rage of countless victims of sexual abuse by clergy — certainly Boston victims, but also others worldwide.

Law's role in the history of clergy abuse is more than the systemic cover-up in Boston. What is little known is the influential part he played in the early days when the extent and depravity of this evil was first exposed. In those very early days in 1984 and 1985, I believed that when the bishops realized the nature of sexual abuse and potential plague before them, they would lose no time in doing the right thing.

Collaborating with Law

I first met Law in 1981 when he was a bishop and I was a newly appointed staff member at the Vatican Embassy in Washington. Our association started when I was asked to do some research for a committee on which he served. From the time we met, I was impressed with him.

He was highly intelligent, read books, actually listened when people talked to him and did not allow episcopal politics to dominate his conversation. We became friends, and before long I would lean on this friendship for help in navigating the sexual abuse crisis that burst onto the scene in late 1984 in Louisiana.

At the time I was working closely with two others who were instrumental in prying off the cover of secrecy the bishops had depended on to keep these horrific crimes from seeing the light of day. At first, the Lafayette vicar general assured the papal nuncio that although several families had complained to the bishop, the diocese entered into confidential settlements with them and all was under control. A few days later we learned one family had not only pulled out of the deal but was suing everyone from the local bishop on up to Pope John Paul II. That's when it all burst into the media.

I had enlisted Mike Peterson, a priest and psychiatrist who ran St. Luke's Institute, to offer to help the diocese deal with Fr. Gilbert Gauthe in a responsible way, which they were not doing at that point. Ray Mouton, the Louisiana attorney of the Diocese of Lafayette, asked to represent Gauthe in the criminal prosecution. Mouton came to see me in Washington when he learned that the diocese knew about several other perpetrators who were still operating in ministry. Mouton was and is a decent man and a father who had three children living in the diocese.

The three of us began to collaborate because we realized the Louisiana scene was explosive. We were also worried about the increasing number of reports of clergy abuse being reported to the nunciature. Mouton was actually the one who predicted massive legal problems if the bishops didn't face the problem head on and do something about it. We decided to put together a position paper that we envisioned would contain all the pertinent information a bishop would need when faced with a report of abuse by one of his priests. This was later commonly known as the "Manual."

Fr. Tom Doyle addresses a crowd at the Voice of the Faithful national conference, in Boston, Saturday, July 20, 2002. Catholics from across the country are attending the meeting in Boston to discuss the sex abuse scandal that has shaken their church. (AP/Steven Senne)

I began to talk to then-Bishop Law about the situation. He agreed about its severity and our predictions if the bishops ignored it. He and I spent a good deal of time discussing the danger posed by perpetrating priests and how bishops should respond to reports. He reviewed our proposed manual, which ended up being about 100 pages long and included several professional articles on pedophilia selected by Peterson.

The soon-to-be cardinal was well aware of the danger facing the church and especially the bishops if they remained inert. He helped work out three action proposals that would include in-depth research into every aspect of sexual abuse, a committee of bishops assisted by independent experts and an office at the U.S. bishops' headquarters that would coordinate immediate responses to particular situations if such assistance was requested by the bishop. He was chairman of the standing committee on research and pastoral practices and offered to set up the sexual abuse committee as a sub-committee. It would be made up of bishops, but the real work would be done by carefully selected lay experts.

Law also assured us that he would "lobby" other bishops to get on board with the action proposals and the creation of the sub-committee. We had planned to meet with him at a Marriott Hotel in Chicago in May 1985. He had been recently named a cardinal, so we were not surprised when he phoned to tell us that he could not make the meeting as it was close to the time of the Vatican ceremony. In his place, he sent then-Auxiliary Bishop Bill Levada of Los Angeles. (Levada, now 81, would be named archbishop of San Francisco and in 2005, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under Pope Benedict XVI.)

Levada met with us for most of a day and was affirmative and approving of all the points of our agenda. About two weeks later, Levada informed me that the entire proposal had been shelved by the leadership of the bishops' conference. The excuse was that it would conflict with the work of another committee that had been assigned the issue of clergy sex abuse. The conversation was short because I was too surprised to argue the point. Not long thereafter I called Law to ask what was going on. He told me he had opposed the move but was limited in what he could do since he had been in Rome when it happened.

Advertisement

Ironically the two others I had worked closely with and who provided valuable advice and support were Anthony Bevilacqua, then-bishop of Pittsburgh and later archbishop of Philadelphia, and Cardinal John Krol of Philadelphia. A 2005 grand jury investigation would find Bevilacqua and Krol successfully shielded from prosecution 63 priests who had sexually abused hundreds of children.

I never knew if Law had put up a fight to save our proposal or not. In one of our conversations he told me that internal politics in the bishops' conference had a lot to do with the non-attention given by the conference leadership. At that time, Law was not one of the "in crowd" at the conference because his ecclesiastical political bent was much more conservative than the leadership.

Mouton came up with the idea of sending a dozen or so copies of our "Manual" with the action proposals to the upcoming national meeting of the bishops planned for June 1985. We knew they were planning a discussion on clergy sex abuse for a one-day executive (therefore closed) session. Since neither Mouton nor Petersen nor I were invited, we asked another bishop we thought was sympathetic to take the copies and give them to bishops he felt would be supportive. That was Auxiliary Bishop A.J. Quinn of Cleveland who not only turned out to be non-supportive, but a part of the cover-up. I had discussed this tactic with Law and he agreed.

We never knew what happened at the meeting other than receiving reports that two out of the three main speakers at the executive session were duds (the general counsel and Kenneth Angell, who was then auxiliary bishop of Providence, Rhode Island, and later bishop of Burlington, Vermont.)

I spoke to Law several times after that, trying to figure out what to do next since it was clear the conference leadership not only planned on doing nothing but would resist any attempts at meaningful action. He suggested sending a copy of the "Manual" to every bishop in the U.S. He subsidized the mailing, which took place on Dece. 8, 1985. He had also provided the funds to pay the professional typist who prepared the final copy of the "Manual."

The problem ignored

I left the Vatican embassy in January 1986 and in June 1986 was sworn in as an officer and chaplain in the Air Force. My contact with Law gradually tapered off not because of any rift between us but probably because of the lack of a common cause to justify collaboration.

I became increasingly involved in the sexual abuse issue. Between 1985 and 2002, there were several major eruptions, including the Jim Porter trial, the Rudy Kos trial and the exposure of multiple perpetrators among the faculties at two seminaries — St. Anthony's in Santa Barbara, California, run by the Franciscans, and St. Lawrence Seminary near Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, run by the Capuchins. In spite of the media attention to each of these and other cases, nothing lit up the Catholic rank and file to the seriousness of the issue. The bishops remained in control giving the expected lip-service followed by continued lying, stone-walling and cover-up.

I learned about the cover-up in Boston in 2001 from Kristin Lombardi, a reporter who was writing a series for the Boston Phoenix. It was a wide-ranging cover-up engineered mainly by Law but one for which his predecessor, Cardinal Humberto Madieros (1919-1983), shared some responsibility. By that time nothing the bishops did surprised me, yet I was still really upset that Law would have been the source of as widespread a conspiracy as had happened in Boston. I collaborated with the Phoenix reporter and learned just how bad it was.

Late in 2001, I was referred to The Boston Globe spotlight team by Richard Sipe, who had been consulting with them. I knew in the first week in January that it was going to hit the fan on Jan. 6, 2002. Having grown cynical that anything would really cause a widespread and effective wake-up call, I expected the Globe coverage would cause a major explosion but then the dust would settle after a couple weeks and it would be back to ho-hum. I was dead-wrong, thank God.

Pope John Paul II speaks with Cardinal Bernard Law in 2002 at the pontiff's private library at the Vatican. (CNS /L'Osservatore Romano)

Cardinal Bernard Law's scandalous cover-up and resignation led to a phenomenon that was not expected nor clearly obvious at the time, but it was real.

I was both saddened and angered by Law's public responses: "If mistakes were made … etc." That line, which he came up with at the first press conference, made me furious. What was worse was that he knew how destructive sexual contact between an adult and a child could be and that the historical cover-up, the default response by the bishops, was a recipe for disaster. He also knew, because we had discussed it enough, how crucial a sympathetic and compassionate response was to the victims and their families. It seemed like everything that had been discussed in 1984 to 1986 had been intentionally buried.

Law's role in the historical development is vitally important. Up to that time it was nearly impossible to get the deposition of a bishop, much less a cardinal. Yet the Suffolk County, Massachusetts, district attorney managed to overcome all the delaying tactics of the archdiocese's lawyers and deposed Law in May 2002. This broke the ice and paved the way for the depositions of a number of other bishops, archbishops and cardinals in sex abuse lawsuits.

Law's resignation was forced by public pressure, increasingly damning media coverage containing more and more revelations and a no-confidence statement by 58 Boston priests. By the time he left in December 2002, the clergy abuse issue had dramatically and fundamentally changed. It was no longer a question of a few Don Quixotes tilting with the massive, powerful and unmovable Catholic Church. Victims and thousands of angry and sympathetic supporters were not only energized, but organized. Victims' support organizations began to make noise that could not be ignored. Several such groups started up in Boston, but it was the Survivors Network of Those Abused Priests, or SNAP, the only effective national group (founded in 1988) that really rose to the challenge and made a significant difference.

Law's scandalous cover-up and resignation led to a phenomenon that was not expected nor clearly obvious at the time, but it was real! In spite of the negative and critical publicity aimed at the bishops, they remained firmly entrenched and in control of the nationwide epidemic. They fully believed they could and would determine how this all played out. Jan. 6, 2002, in Boston changed that. Now for the first time in the history of the church, the victims of the clergy's malfeasance were in charge, whether they fully realized it or not. The Catholic laity, the general public and especially the victims called out Law's empty rhetoric and continued to challenge bishops from then on for their baseless and self-serving assertions and lack of follow-through. Law's downfall marked a rapid increase in the erosion of the traditional deference for the hierarchy and the institutional church in general.

U.S. Cardinal Bernard Law, center, is pictured in a 2014 photo at the Vatican. (CNS/Paul Haring)

The Vatican takes notice

The Boston event and the public reaction to the cardinal's presence brought the seriousness of the issue home to Catholics in other countries but especially to the Vatican. Pope John Paul II summoned the American cardinals to Rome in April 2002 for a meeting that was substantially useless, yet it showed that the pope and his Curia could no longer ignore the reality of the problem even though they continued to try and minimize it and shift the blame elsewhere. It would only be a matter of time before officials in the Vatican itself would be uncovered. The first and highest-ranking hierarch to fall was not a lowly diocesan bishop from somewhere in the boondocks but the most powerful cardinal in the United States and a close collaborator to the pope. After that no one was off limits or out of bounds. The victims knew this all along but now the Catholic faithful and the public knew it. It was another harsh reminder of just how horrific it was to condone sexual abuse of anyone much less a child.

Law's brazen cover-up and his public downfall caused massive scandal to the U.S. church. In any normal organization, it would have meant the end of the line for him but this was the monarchical Catholic church, where up is often down and black is usually any other color but black.

After a few months, Pope John Paul II made Law the archpriest of the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, which carried with it significant perks as well as a palace to live in. He remained an influential member of several Vatican congregations. This screamed volumes about the pope's complete insensitivity to the incalculable harm done to the people of the Archdiocese of Boston but most importantly, the harm done to victims.

Many who thought the Vatican would do something began to learn just how out of touch the papacy and the Curia really were and how obsessed they were with their own welfare. This hasn't changed in spite of the seemingly sympathetic rhetoric. All talk but no action, then and now.

Law's life after Jan. 6, 2002, was no doubt marked by a good deal of personal pain, stress and bewilderment. He was the center of a phenomenon in Catholic life that was unheard of: the public disintegration of the life of a prince of the church culminating with his resignation and departure in disgrace.

In spite of the opprobrium heaped on him, his actions in Boston were far less blameworthy than several of his brother bishops: Cardinal Roger Mahony of Los Angeles, Cardinal Edward Egan of New York, Archbishop John Neinstedt of St. Paul-Minneapolis, Archbishop John Myers of Newark, New Jersey, Bishop Robert Finn of Kansas City, Missouri, to name but a few. These men and others not only engineered multiple cover-ups blanketed in lies, but in many instances, they "punished" victims for challenging the church in court by allowing and even encouraging their attorneys to attack, humiliate and eventually re-victimize them.

When Law finally realized his stature and his power had eroded, he asked Pope John Paul II to allow him to resign. Twice the pope refused, indicating his own blindness to the plight of the victims and faithful of the Boston archdiocese. The pope finally acceded in December 2002, and thus Law became the first and only American hierarch to resign because of his role in the clergy abuse scandal.

I'll always wonder if Law fundamentally changed when he had to face sexual abuse by his own clergy right in his own back yard. It no longer was an impersonal problem far removed from his world. I wondered if his response in Boston was really a tragic manifestation of skewed loyalty to the hierarchy's bizarre notion of the meaning of church.

Whatever is true is dwarfed by his impact on the unfolding sexual abuse phenomenon in the modern church. He is a tragic anti-hero because his actions as archbishop were the catalyst for fundamental and far-reaching changes in the Catholic clerical culture and in the victims' and laity's realization that their days as docile, silent sheep are forever dead.

[Thomas P. Doyle is a priest, canon lawyer, addictions therapist and long-time supporter of justice and compassion for clergy sex abuse victims.]