An unidentified man with Alzheimer's disease, who refused to eat, sleeps peacefully the day before passing away in a nursing home in Utrecht, Netherlands. (CNS/Reuters/Michael Kooren)

Less than two weeks before Pope Francis signed and released his third encyclical, Fratelli Tutti, the Vatican Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith promulgated another document, "Samaritanus Bonus: On the Care of Persons in the Critical and Terminal Phases of Life," a letter that reaffirmed the church's opposition to euthanasia and said that patients planning to end their lives cannot be granted access to the sacraments.

Both documents draw on the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37) to affirm human dignity.

The letter followed the congregation's March ruling that the homes for psychiatric patients founded by the association of the Brothers of Charity in Belgium could no longer be considered Catholic because, since 2017, the association complied with the legal requirements set by the Belgian law on euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, and violated Catholic official teaching.

The congregation repeatedly expresses concern for the presence, in various countries (without indicating them explicitly) of legislation aimed at the depenalization or regulation of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, as well as for personal or social attitudes that might lead to accepting or promoting these practices.

As the good Samaritan does, the letter, in its first and shorter part (Sections I-IV), reaffirms human dignity: how human beings are created at the image of God; how compassion and care should be promoted, from conception to the end of life. Hence, with the generosity of the good Samaritan, the letter could be read as challenging any attempt to limit providing health care services to every citizen in need.

Advertisement

One notices, however, that something is missing. Does it make a difference to reflect on the end of life, and on its ethical challenges, in diverse contexts? In the majority of the world, how do people die? As we know too well, in the Global South the ethical issues that people face during and at the end of their lives are quite different from what happens in the Global North.

To promote the common good in effective and comprehensive ways across the planet, Catholic social teaching invites us to critically examine each specific social, cultural and religious context by focusing on the structural conditions and their sinful power dynamics that inhibit flourishing and that limit caring for people in need (IV, footnote 35). Globally, to provide care justly, social changes are needed to promote a consistent ethic of life.

In its second and longer part (Section V), the letter articulates the teaching of the magisterium by addressing 12 specific issues. One wonders, however, what happened to the good Samaritan and the compassion and care that inform the Samaritan's actions and that shape the first part of the letter.

Repeatedly, the letter refers to God's grace as essential in living and ending our lives, as well as in our social and ecclesial life. Every believer knows that God's grace is at the core of receiving and administering the sacraments. God's grace is infinitely merciful — as Francis continues to stress, from his 2016 apostolic letter Misercordia et misera, which celebrated the conclusion of the extraordinary jubilee of mercy, to his 2016 post-synodal apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia, which focuses on the pastoral care of families.*

The good Samaritan lives according to grace, and the half-dead person on the side of the road benefits from the many concrete ways in which the good Samaritan is embodying grace and going the extra mile for this unknown person. By receiving such grace, the life of this needy person is changed, healing occurs and hope is renewed.

But the parable also tells us about who lacks grace, does not care for the person in need, turns on the other side of the road and walks away. The priest — representing the law — and the Levite — representing the religious cult — do not bother to care for the person in need. They are not changed by who is in need. Their hearts are hardened, despite their familiarity and love for the precepts of the law and for how the cult celebrates God.

On administering the sacraments, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith stresses that penitents who decided to be euthanized or are seeking physician-assistant suicide can only receive the sacraments (i.e., Penance, Anointing and Viaticum) "when the minister discerns his or her readiness to take concrete steps that indicate he or she has modified their decision in this regard" — for example, a person "registered in an association to receive euthanasia or assisted suicide must manifest the intention of cancelling such a registration before receiving the sacraments" (V, 11).

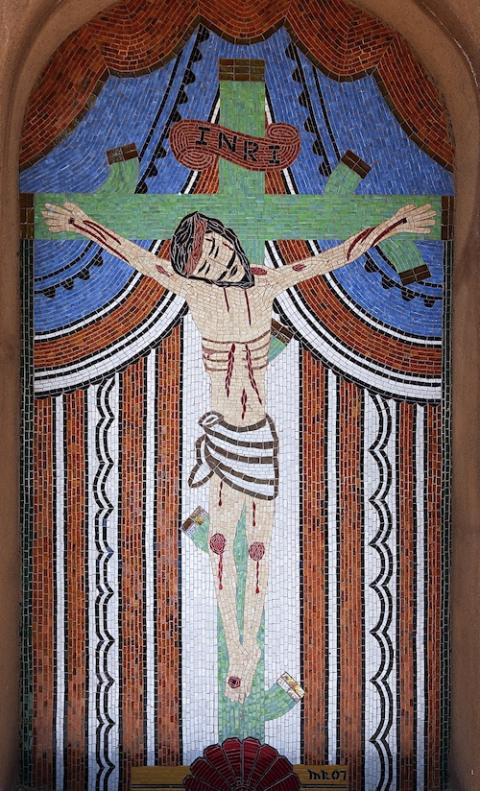

Mosaic of Jesus crucified at El Santuario de Chimayo in Chimayo, New Mexico, pictured in 2015 (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

Together with the focus on conversion, the congregation is concerned about scandal and aims at avoiding it (V, 11). Going beyond Luke's parable, the Gospels tell us how for some Pharisees Jesus' ministry was scandalous because Jesus was sharing meals with sinners and caring for them as God does. For them, Jesus's death on the cross was the ultimate scandal.

But Jesus did not turn away from those Pharisees. He was not scandalized by their behavior. He gave his life out of love for everyone, even for those Pharisees who did not think they needed God's mercy, and who did not ask for the gift of conversion of their hearts. Notably, the parable of the good Samaritan is offered as a gift to a doctor of the law.

Understandably, the congregation wants to avoid scandal in the sacramental practice. A few days ago, in a course on theological bioethics, my students and I discussed another case in which the church's authority acted to avoid scandal. One student commented: We should also consider that the faithful could be scandalized by what the hierarchy requires in order to avoid scandal, or by what the hierarchy omits saying and doing. In other words, this student flipped and expanded our understanding of scandal.

Within the church, at all levels, we should be attentive to critically examine our actions. We are all sinners in need of the gift of conversion. What changes us is God's grace, which we experience concretely in so many ways, from the sacraments to many acts of caring and loving accompaniment — just as the good Samaritan.

The sacraments are not prizes given to winners by the priest and the Levite. The sacraments are one of the special ways in which God's grace reaches out to us sinners, changing our hearts and lives during our life journey and at the end of our lives.

* This sentence has been updated to correct the date of the apostolic letter.

[Jesuit Fr. Andrea Vicini is professor of moral theology and the Michael P. Walsh Professor of Bioethics at Boston College.]