Fr. William DuBay in Los Angeles, around 1968 (Wilkimedia Commons/Bdubay)

There was standing room only on June 11, 1964, when a boyish-looking young priest named William DuBay called a press conference to criticize Los Angeles Cardinal James Francis McIntyre for ignoring housing discrimination against African Americans.

Quoting from a letter he wrote to Pope Paul VI, DuBay protested against the cardinal for "gross malfeasance in office" and asked that he be removed as archbishop of Los Angeles.

Suddenly, the young cleric became a household name on network news and the front pages of most daily newspapers.

"I was quite nervous and tense as a large group of print and television reporters took their seats," DuBay, 84, recently said in a telephone interview from his home on Whidbey Island near Seattle. "I kept reminding myself that it was the right thing to do."

Ordinarily, the media never covered church protests without checking first with the Los Angeles chancery office. "I did an end run, hoping I would break through any attempts at censorship," DuBay said. "It worked."

DuBay stood alone. Even his most loyal priest friends declined to join him to face the press.

"Isn't this insubordination?" asked one reporter. DuBay responded, "It's nothing compared to the insults suffered by hundreds of thousands of Negroes at the hands of white Catholics who the church has failed to instruct regarding racial justice."

Upon returning to his rectory, a man called and cursed him, suggesting that he "crawl on his belly to Cardinal McIntyre to forgive your Judas soul. May you rot in hell!"

A few days later, McIntyre demanded that DuBay kneel before him at a priests' retreat and take an oath to uphold the church's teaching against the heresy of modernism.

"McIntyre was in tears," DuBay said. "He feared there would be a schism, since the Vatican was making overtures to blacks throughout the world and had just named a black cardinal in Africa."

"Some priests gave me thumbs-up," he said. "Others scowled and called me a publicity hound."

Daniel Callaghan wrote in Commonweal at the time: "It is a shame that a priest should feel compelled to castigate his Ordinary in public. Only on the rarest of occasions should he actually do so. Los Angeles, 1964, is one of those occasions."

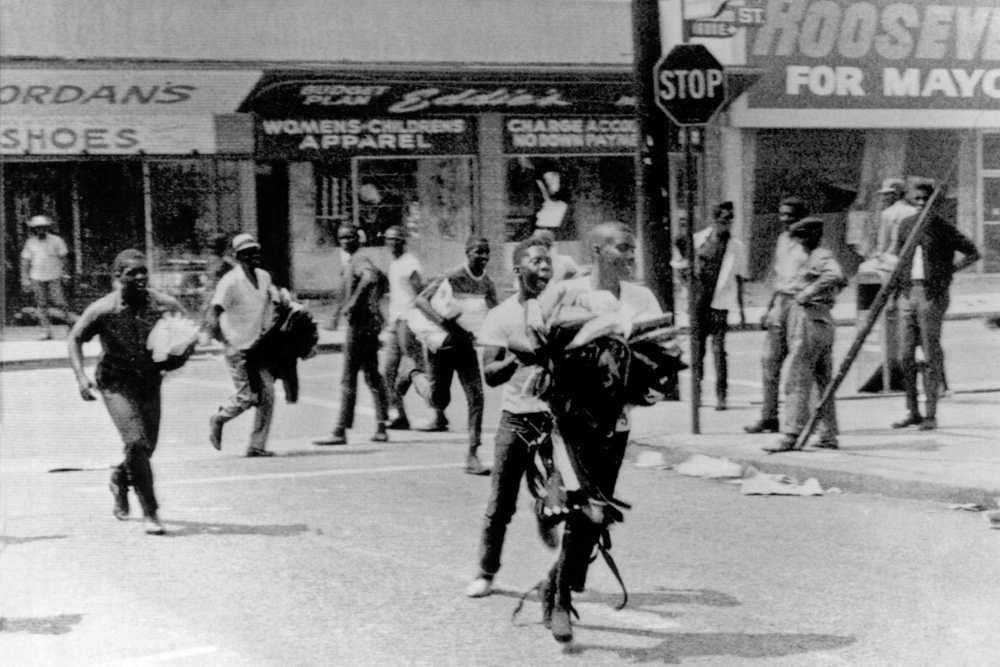

Young people during the riots in the Watts section of Los Angeles, August 1965 (Newscom/Underwood Archives/UIG)

More than five decades later, DuBay memorialized this struggle in his book The Priest and the Cardinal: Race and Rebellion in 1960s Los Angeles.

DuBay wrote about the low morale of his fellow priests who worked under conservative pastors. "There was no relief," he wrote. "It was like living with your boss. The pastors were as resistant to change as the cardinal."

In the years following the Second Vatican Council, wrote DuBay, more than 12,000 men left the ministry, and 130,000 nuns abandoned their orders. Some, such as the Immaculate Heart sisters in Los Angeles, took their convents with them.

DuBay had tacit support from many fellow priests for airing his grievances. But some cautioned him against speaking out too strongly.

Said classmate Terry Halloran, "Everybody was upset that the cardinal was ignoring Vatican II and social justice issues, but nobody wanted to do anything but talk about it."

In his book, DuBay described how he denounced racial discrimination from the pulpits of four different parishes. Though McIntyre built 19 churches and schools in the black community, he resisted any attempts to integrate blacks into the wider fabric of Los Angeles society.

In short, his views were racist.

Advertisement

When the Rumford Fair Housing Act was passed in 1963, McIntyre vigorously opposed it. A year later, he backed real estate interests who sought to repeal the act with Proposition 14, a ballot initiative.

Experts believe the repeal of the Rumford Act, along with police brutality and job discrimination, were instrumental in fueling the Watts uprising in 1965.

The initiative easily passed, but it was repealed 10 years later, based on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

On one occasion, wrote DuBay, a group of prominent black Catholics met with McIntyre to discuss community problems. He accepted them graciously, then said, "While in Rome recently, I met with your cardinal, Laurian Rugambwa, a remarkable man." (Rugambwa of Tanzania was the first modern-era native African cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church.)

Ivan Houston, an insurance executive, responded: "Your Eminence, you are our cardinal, and this is why we came to talk you."

Meanwhile, another group, Catholics United for Racial Equality (CURE), demanded reforms. They wanted an interracial council, a pastoral letter on discrimination, and more black teachers in Catholic schools. McIntyre said no.

"We had marches, sit-ins, and even a torch-light procession in front of the cardinal's home," said CURE activist Sue Welsh, a young graduate of Immaculate Heart College. "After I appeared on the NBC news that night, they sent two priests to my house looking for me. It was crazy. They called us communists and outside agitators from their pulpits."

Only later, said Welsh, did they find out that the protesters were all Catholics. "We were just putting into action what we learned from Catholic schools," she added.

"We had marches, sit-ins, and even a torch-light procession in front of the cardinal's home. After I appeared on the NBC news that night, they sent two priests to my house looking for me. It was crazy. They called us communists and outside agitators from their pulpits."

— CURE activist Sue Welsh

Soon after the sit-ins, creole Catholics from Louisiana and their white allies in CURE moved their meetings to a barber shop owned by community activist Leon Aubry. DuBay regularly attended the gatherings that included singer Nat King Cole and Tom Bradley, the future mayor of Los Angeles.

Other priests were also targeted by conservative parishioners and the cardinal's consulters. "I knew 12 of them, said Terrence Halloran. They were called the CCC — the Cardinal's Carpet Club." (Halloran died in May 2018.)

Each priest had to meet first with Msgr. Benjamin Hawkes. He would present the charges to McIntyre, who then reprimanded the cleric.

Hawkes, feared by most priests, resigned as chancellor in 1985. Years later, several former altar boys accused him of physical, mental and sexual abuse. "Why didn't someone help us?" asked one of the accusers in a letter to the court. "This whole ugly thing could have been stopped."

After ordination, DuBay was assigned to two predominantly white parishes north of Los Angeles: Our Lady of Lourdes in Northridge and St. Bede in La Cañada. Both had parishioners who worked in the burgeoning aerospace industry.

"Two parishioners at St. Bede's were prominent in the oil industry," said DuBay in his telephone interview. "This included the wife of oil baron Harry Sinclair, who served prison time for his role in the Teapot Dome scandal, as well as the vice president of Richfield Oil. The latter told me point blank to stop preaching on civil rights and housing discrimination."

Again, DuBay was scolded and transferred, this time to St. Albert in Compton, a black ghetto known for its extreme poverty and crime.

"On one occasion, a woman approached him after Mass with a whimpering child," DuBay said. "When I asked the child why she was crying, she wiped her eyes and said, 'I don't want to be black.' Her mother turned to me and asked, 'Just what are we supposed to be telling our kids?' "

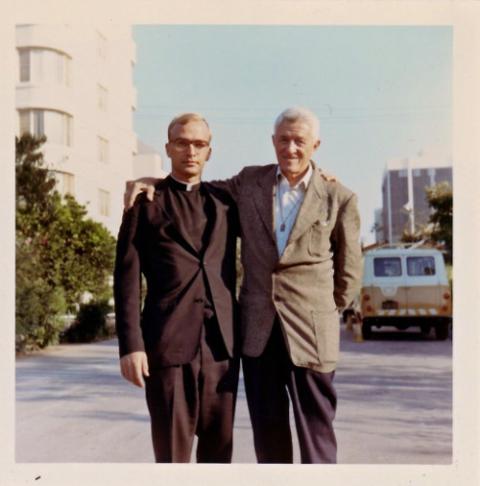

Fr. William DuBay with pacifict and Catholic Worker Ammon Hennacy at St. John's Hospital, Santa Monica, California, July 1966 (Wilkimedia Commons/ William DuBay)

DuBay intensified his activism at St. Albert's, organizing a human relations committee, interracial home visits, and fair housing rallies. McIntyre scolded him again, sending him to a parish in Orange County with strict orders that he cut all ties with St. Albert's.

In February 1966, when Doubleday published DuBay's book, The Human Church, McIntyre suspended him from the priesthood. The book called for the democratizing of the Catholic Church. It also urged the church to abandon its tax-exempt status and allow congregations to create their own liturgies.

Since his departure from the ministry, DuBay has worked as a technical writer and editor and has authored three books, including a sociological study called Gay Identity: The Self Under Ban.

"I had a three-year marriage in 1968 that ended in divorce," he said. "We had a son named Alfred who currently lives in nearby in Poulsbo, Washington."

In 1971, DuBay came out as gay and became active in the gay pride movement. He conducted a ministry to gay prisoners at the Washington State Penitentiary at Walla Walla and co-founded a halfway house in Seattle called Stonewall.

DuBay said that after 60 years his core message has not changed. "The church has been hobbled by its top-down structures for too long," he said. "Unless Pope Francis gives priests and laypeople the right to elect bishops, I don't see much hope for it."

As for black Catholics in Los Angeles, many believe their plight hasn't changed much in 60 years. "No, not at all," said Tom Honoré, a former priest and creole Catholic from Louisiana.

"Cardinal Roger Mahony, who retired as archbishop in 2011, closed down the office for black Catholics in the chancery office for budget reasons," he said. "There hasn't been a black priest ordained in 15 years, and there are currently no black seminarians in the archdiocese."

Meanwhile, black Protestant denominations are flourishing. The Rev. James Lawson, an emeritus Methodist pastor in Los Angeles and a close associate of the Rev. Martin Luther King, is a revered figure in the black community.

"We need to speak out and take our country away from empire building," he said at a recent memorial for the late social activist Blase Bonpane. "We need to build Dr. King's beloved community. That's where we need to be."

[Mark R. Day covered the West Coast for NCR in the early 1980s.]