Helen Dery Woodson, shortly after she was released from federal penitentiary for the last time in 2011. Woodson, a Catholic peace and environmental activist, died Dec. 2 at age 80. (Courtesy of Jane Stoever)

Catholic peace and environmental activist Helen Dery Woodson, whose bold actions befuddled both the judicial system and often her fellow peace activists, died Dec. 2 of heart failure. She spent 27 years in jail and federal prison for acts of civil disobedience ranging from sabotage to bank robbery.

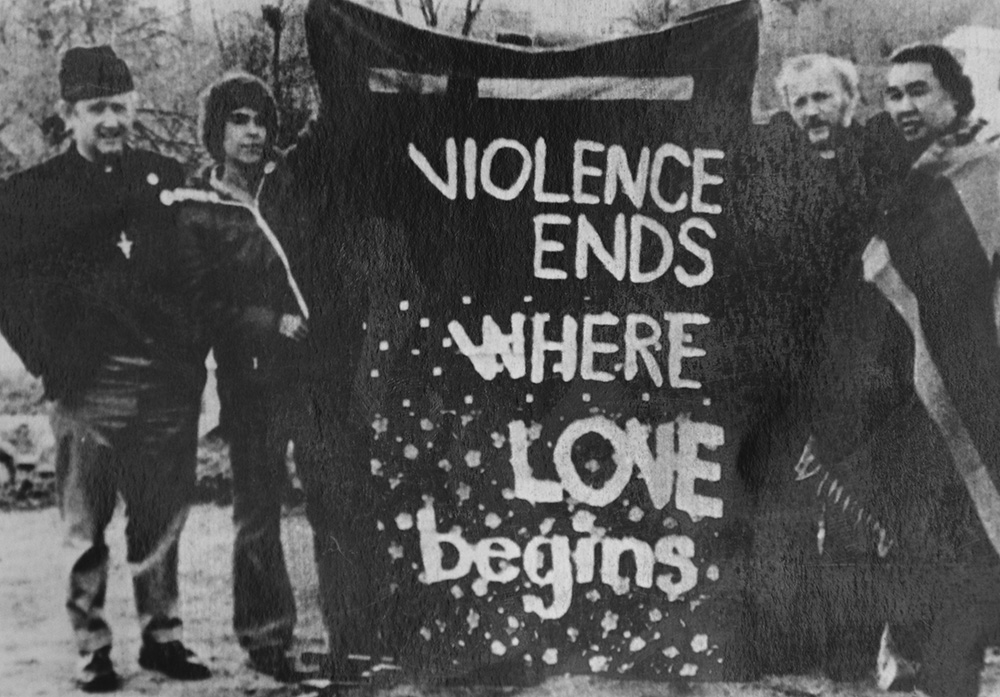

Woodson, 80, is best remembered for her initial daring "Plowshares disarmament action" she engaged in with Oblate Frs. Carl and Paul Kabat, biological siblings, and Native American peace activist Larry Cloud Morgan.

On Nov. 12, 1984, the foursome, calling themselves the "Silo Pruning Hooks," a reference to Isaiah 2:4, cut a padlock on a fence surrounding a Missouri-based ICBM silo containing a Minuteman II nuclear-armed warhead. Using a rented jackhammer to chip away some concrete — the damage was negligible — resulted in sabotage charges and shockingly long prison sentences.

Woodson, the last of the four to die, and Carl Kabat, both received 18-year sentences. Paul Kabat received 10 years and Cloud Morgan eight years.

Following her release from federal prison in 1993, Woodson changed tactics when she held up a Chicago bank on June 17, 1993. In a newsletter, Woodson wrote she was sent back to prison for robbing the bank, lighting the stolen bills on fire and "distributing a statement denouncing the materialism and obsession with wealth and power that caused environmental destruction, wars and various other social ills. For this, I was convicted of robbery by force."

In a third incident, Woodson mailed what she called "warning letters with .38 caliber bullets affixed" to various government and corporate officials, including the chief justice of the Supreme Court, two corporate CEOs and the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Woodson wrote that her "letters said that their actions were like bullets fired into the heart of creation. For this, I was convicted of threatening communication and being a felon in possession of ammunition."

Advertisement

The Nuclear Resister, a quarterly publication that serves "as a clearinghouse for information about contemporary nonviolent resistance to war and the nuclear threat" published an account of the bank caper in 1993:

Three days after her release, Woodson walked into a Chicago bank, produced a starter's pistol and asked the teller to empty all the cash drawers. When patrons began to catch wind that something was amiss, Woodson announced she had no intention to harm anyone, and asked everyone in the bank to please sit down and hear her statement.

After receiving about $25,000 in cash, Woodson piled it in the middle of the floor, doused it with lighter fluid, and ignited it. She made a statement elaborating on her belief that money is the root of all evil.

Cash now ashes, Woodson asked the patrons to leave the bank with her. If police were waiting, she would surrender peacefully; if not, she intended to walk on to other planned actions. Police were waiting, and Woodson was taken back into custody.

Tom Hastings, a fellow peace activist who visited Woodson in prison, called the bank robbery, "Helen's Woody Allen caper," a reference to Allen's 1969 comedy, "Take the Money and Run."

In the film, Allen's character botches a bank robbery when he gives the teller an unintelligible hold-up note.

"It was a silly action that she did in my view, that was symbolically meaningful to her," Hastings told NCR. "It was meaningless to a lot of us. You could not stack it up against their incredibly powerful Plowshare action."

Hastings, who also was jailed for two Plowshare actions, gave Woodson high praise when he compared her to Philip Berrigan, the late founder of the Plowshares movement: "Outside of Phil Berrigan you couldn't really find any resister who was more committed than Helen Woodson. She just didn't have the through lines that somebody like Phil had. She had different through lines of her own."

From left: Oblate Fr. Paul Kabat, Helen Woodson, Oblate Fr. Carl Kabat and Larry Cloud Morgan after they used a jackhammer to damage a Minuteman II missile silo cover at Whiteman Air Force Base in Knob Noster, Missouri, Nov. 12, 1984 (CNS/Bob Roller)

Woodson was a person who let her actions speak louder than her words. Although well-educated, Woodson, who held a master's degree in library science, rarely wrote any articles or gave interviews about her beliefs or actions. She did maintain friendships with many, mostly Catholic peace movement friends, through letters and phone calls.

Woodson made an exception when she agreed to an interview with the late Washington Post columnist Mary McGrory, who visited Woodson at Federal Correctional Institution Alderson, a West Virginia prison for women.

In her April 15, 1986, column titled "Saga of an American Dissenter," McGrory wrote:

I first heard about Helen Woodson in Moscow. During a human rights discussion with weathered, wary Kremlin officials, one burst out, "Everyone speaks of [Soviet dissident Andrei] Sakharov. What about in your own country a female, the mother of seven, imprisoned for 18 years for damaging a Minuteman missile concrete? Nobody speaks about it. Nobody writes about it."

Clare Grady of Ithaca, New York, who was incarcerated at Alderson with Woodson for a different Plowshares action, called Woodson a "bright, warm, funny and faithful sister."

"While my two-year sentence in the mid-'80s was brief, I'm so glad I had overlapping time with Helen," Grady told NCR. "All the years that Helen was imprisoned, she never complained, despite much physical pain and challenges. Her heart was singularly focused, and continued to be as she was released and devoted her time praying for peace."

Helen Woodson plays the piano for Jane Stoever. (Courtesy of Felice Cohen-Joppa)

Jane and Henry Stoever of Overland Park, Kansas, attended the Silo Pruning Hooks trial, and Henry, a lawyer, also facilitated pretrial jail meetings for the four defendants. Woodson lived with the Stoevers for six months after her final prison sentence ended, and the couple remained in contact with Woodson ever since. Both Jane and Henry visited Woodson in the hospital during the final week of her life.

Henry said Woodson was criticized for leaving her children behind to go to prison. "Some person said, 'How could a woman just walk away from those kids?' And Helen's response was, 'If I was a male and I was sent to Vietnam or somewhere else people would say, "Thank you for your service," slap you on the back.' And she said, 'This is a world crisis. I am doing what I believe God has called me to do.' "

Jane said Woodson was a good pianist, and filled their home with "noise from the piano and singing. ... She clung to the happiness."

Jane said Woodson "had very strong views that were different from some of our views. She had a highly conservative theology, and she would argue chapter and verse and give you biblical citations."

"Still we loved her, and she loved us," said Jane.

Nuclear Resister founders Felice and Jack Cohen-Joppa were close friends with Woodson for more than 40 years.

"She was absolutely clear and consistent and faithful in what she felt needed to be done in the world to get rid of nuclear weapons, and she never wavered from it," Felice said.

Jack Cohen-Joppa teaches Helen Woodson how to use a computer, following Woodson's final release from federal penitentiary in 2011. (Courtesy of Felice Cohen-Joppa)

In 2011, Woodson, who had always said she would likely die in prison, changed her mind, and announced she was going to "retire" from activism when she was released from prison after a combined 27 years.

"She said she was going to retire and she did," Jack said. "Even though that was a change of heart from her. And when she left prison, she was done."

During retirement, Woodson did not maintain contact with her former codefendants and most of her peace movement friends to avoid being sent back to prison for a probation violation.

"She was happy in her post-prison life by all indications," Jack said.

Hastings said Woodson "followed her own light." While he honored Woodson's commitment, "I just didn't follow her line of thinking," he said.

"She never exhibited a single bit of self doubt. There was really no other way to look at it. There was no gray area," he said. "There was little point in arguing with Helen Woodson. When she said something, you just kind of rolled with it."

Woodson's funeral will be held Dec. 11 at her parish, St. Rose Philippine Duchesne Catholic Church in Westwood, Kansas. The church only celebrates Mass in Latin, calling itself a "personal parish of the Archdiocese of Kansas City in Kansas."