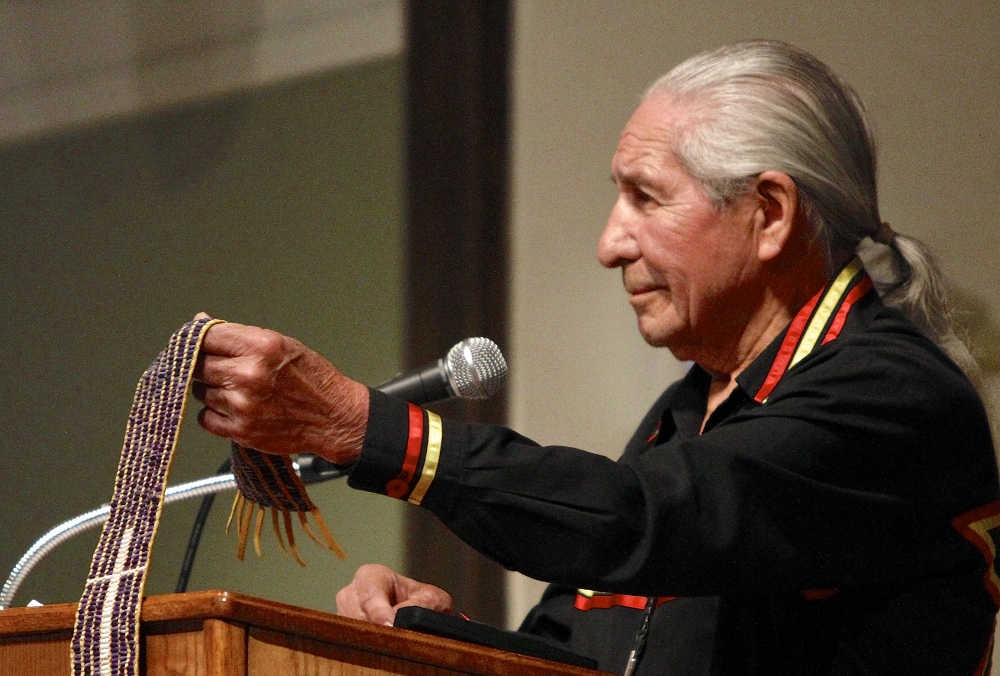

At a 2013 event at Le Moyne College called "Listening to the Wampum," Oren Lyons holds the Jesuit Belt, or the Remembrance Belt, which depicts the history of contact between French Jesuits and the Onondaga in the 1650s. Wampum belts are made of beads that create patterns that tell a story. (Michael Davis)

When Onondaga Nation faithkeeper Oren Lyons accepts an honorary degree Sunday, May 20, at Le Moyne College, the Jesuit institution will recognize his international advocacy for indigenous peoples, human rights and environmental stewardship. The award also honors the Haudenosaunee Confederacy in the college's first public acknowledgement that the Jesuits harmed the region's original inhabitants as they sought to convert them in the 17th century.

"We didn't need them to convert us," said Lyons, 88. "We knew who our creator was."

Lyons grew up at Onondaga, the capital of the Haudenosaunee, which the French missionaries called the Iroquois Confederacy. The Onondaga Nation — which encompasses just 7,300 of its original 2.6 million acres south of Syracuse — lies about 8 miles from Le Moyne College, named for Simon Le Moyne (1604-65). Between 1654 and 1662, the French Jesuit missionary traveled several times from New France (Canada) to what is now New York state.

In summer 1654, Le Moyne visited an Onondaga village in what is now a Syracuse suburb. "I baptized some little skeletons who, perhaps, were only waiting for this drop of the precious blood of Jesus Christ," Le Moyne wrote. On Aug. 15, 1654, he baptized his first Onondaga convert, according to The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, a collection of contemporaneous records of missionary activities from 1610 to 1701.

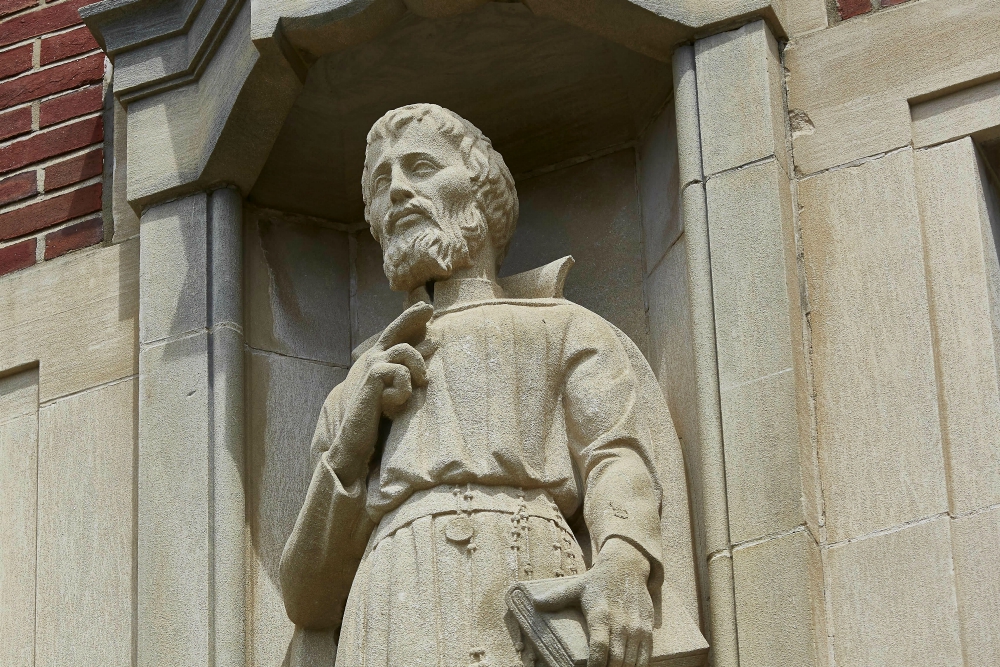

During that trip, Le Moyne made arrangements for a Jesuit mission near Onondaga Lake, sacred to the Haudenosaunee as the site of their confederacy's founding 1,000 years ago. Sainte-Marie de Gannentaha operated for just two years before the Jesuits fled in 1658. Among the seven Jesuits at the mission was Fr. Claude Dablon; a Le Moyne College dormitory built in 1963 is named after him. A sculpture of Simon Le Moyne sits in front of Grewen Hall, the 72-year-old college's oldest building.

To Lyons, the 17th-century missionaries "were bad people. They're responsible for ecocide and ethnocide. They came in and our nations were lost. They interfered directly in our communities."

He blames them for carrying European diseases that killed Native peoples, for squelching Native languages and traditions, and for stirring discord among indigenous peoples.

The Jesuits' forays into Turtle Island (North America), Lyons said, opened the way for generations of racist and colonial policies that robbed Native Americans of their land and livelihoods. "Now we're fighting for our lives," he said.

Lyons' honorary degree acknowledges the Jesuits' role "on the frontiers of colonization," said Jesuit Fr. David McCallum, Le Moyne's vice president for mission integration and development. The history is "filled with violence and bloodshed of innocent Native peoples," he said. "We need to come to terms with this history and the devastation it's caused over the centuries."

A sculpture of Jesuit Fr. Simon Le Moyne sits in front of Grewen Hall at Le Moyne College in Syracuse, New York. (Courtesy of Le Moyne College)

McCallum, Lyons and others have met monthly for nearly two years to discuss how to reconcile distinct versions of the Jesuits' interactions with the Haudenosaunee during the 1600s and 1700s. Indigenous peoples — and, increasingly, scholars and allies — see racism, arrogance and greed motivating European Christians to colonize people and exert dominion over the land.

The Catholic Church traditionally describes the missionaries as exemplars of courage and faith. Even amid efforts toward reconciliation and healing, the college's website links to the Catholic Encyclopedia, which lauds Le Moyne's "undaunted courage and eminent virtues." The Jesuit priest "was unequalled in the knowledge of the character of the Indians their customs and traditions, even the artifices of their savage eloquence and diplomacy," the entry reads.

The damage continues, Lyons said, pointing to poverty and health disparities among Native Americans. He attributes the Native American suicide rate — the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says it's the highest of any racial/ethnic group in the United States — to generational trauma.

"That comes from having your identity taken away," Lyons said. "We received all that racism and we still are."

Sunday's honorary degree is one step toward healing those "deep wounds" caused by "the well-intentioned efforts by Jesuits 400 years ago to establish relations and to bring the faith of Catholicism" to them, McCallum said.

The college will soon begin flying the Haudenosaunee flag on its campus. Le Moyne will also open major campus events by noting its location on the ancestral lands of the Onondaga Nation.

Plans are underway for a yearlong symposium on dialogue and healing between the Jesuits and the Onondaga, but McCallum does not expect immediate resolutions. "It would be naive to think that one story will speak for everyone," he said.

Jesuit Fr. David McCallum, left, and Oren Lyons converse at Le Moyne College in 2013. (Michael Davis)

The indigenous perspective is new to McCallum, a 1990 Le Moyne graduate.

"I still have loads of respect for those Jesuits because I realize they were entirely dedicated to the good of the people they sought to evangelize," he said. "They also had blind spots, like we all do, for the consequences and the implications of their presence and their actions."

Lyons has been talking about cultural identity and Native sovereignty most of his life. He left a commercial art career in New York City in 1970 to take on the role of faithkeeper, maintaining Haudenosaunee traditions and history. He was a central figure in creating the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations and speaks frequently about indigenous rights at the United Nations and on other national and international stages.

He's pleased at Le Moyne's efforts thus far, but he hopes the Jesuits will convince the Vatican to renounce the Doctrine of Discovery. The concept, which emerged from 15th-century papal decrees, condoned the conquest of the Americas and other lands inhabited by indigenous peoples. Vatican officials have said subsequent papal bulls "abrogated" the Doctrine of Discovery.

Le Moyne's symposium will address the Doctrine of Discovery, McCallum said. It will also be part of the curriculum for a course the college is developing. "We hope that our study and dialogue have implications for meaningful next steps," he said.

Le Moyne's dialogue parallels Georgetown University's Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation project.

"In both cases, we're trying to deal with the legacy of the past and the effects of that in the contemporary world," said Fr. James Miracky, provincial assistant for higher education for the Jesuits' USA Northeast Province. "How can we reconcile Jesuits being involved in a history of colonialism and the ways in which our missionary work was intertwined with that past?"

Advertisement

In 2016, Georgetown hosted a public ceremony to honor the 272 enslaved people that Jesuits in Maryland sold to Louisiana plantation owners in 1838. The university also renamed two buildings that had been named for Jesuits involved in the sale.

"Because we are profoundly sorry, we stand now before God — and before you, the descendants of those whom we held enslaved — and we apologize for what we have done and for what we have failed to do," Jesuit Fr. Timothy Kesicki, president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, said at that event.

The first step for Le Moyne is to reconcile with the past, McCallum said. Public acknowledgements and campus programs about the Haudenosaunee will educate students about the complex history, he said.

Of 2,500 undergraduate and 650 graduate students; 10 self-identify as Native American, the college said. Officials do not know if any are Haudenosaunee or Onondaga. Le Moyne offers three scholarships for Native American students.

Lyons says it's up to Le Moyne to decide what statues to display or what to name buildings. He concedes meaningful dialogue will take time, but he admires McCallum's commitment to difficult conversations. "It takes courage to face people who have been victims," he said. "It takes courage to listen."

Does Lyons forgive the Jesuits? "That's not for me to decide," he said.

[Renee K. Gadoua is a freelance writer and editor in Syracuse, New York. Follow her on Twitter: @ReneeKGadoua.]