Participants pray together after the spring planting and dedication of raised beds at Friendship House in Fayetteville, North Carolina. (RNS/Courtesy of Avery Cameron)

At the evening prayer service at a new residential complex here, a dozen young people took turns reading a passage from the Gospel of Luke, reciting a Psalm and singing some prayers.

They paid no mind as one woman tripped over the words "rebuke," "unrighteous" and "snare" that appeared in the liturgy. They congratulated another person who, at the end of the Lord's Prayer, blurted out, "What does 'amen' mean?"

"Good question!" some exclaimed in unison. It means "truly," offered one; "so be it," offered another.

These kinds of moments are common at the weekly service where a mix of graduate students and a handful of adults with developmental disabilities share living quarters in three new buildings in the city's Haymount neighborhood.

Friendship House, as they call their co-housing space, is in many ways an outgrowth of the thinking of Jean Vanier, the Catholic theologian and humanitarian who died May 7 and who changed the way many Christians view disability. Insisting on the humanity of all, Vanier worked to tear down the separation between the able and disabled and between those helping and those being helped.

Two of the three Friendship House buildings in Fayetteville, North Carolina (RNS/Yonat Shimron)

His signature creation was L'Arche, a worldwide network of homes where people with and without disabilities live and work as peers. The influence of L'Arche can be found in Friendship Houses, which have adopted Vanier's core principle of "Eat together, pray together, celebrate together."

There are seven Friendship Houses in the U.S. and one in Scotland. The Fayetteville Friendship House, which opened late last year, is the newest and most novel. While other Friendship Houses are affiliated with seminaries or Christian universities, Fayetteville's is intended to allow students in health care professions the opportunity to learn from disabled people.

It is the brainchild of Scott Cameron, a physician and a graduate of Duke Divinity School, who realized he needed to change his own attitude about some of the diagnoses he delivers to parents of babies he cares for in the neonatal intensive care unit at Cape Fear Valley Medical Center. With Friendship House, Cameron aims to extend that insight into a larger group of health care students.

"I think it will help them change the way they view disabilities, not as something that is broken, but something that can be celebrated," he said.

Advertisement

Cameron and his family — his wife is a public school teacher — moved into a newly constructed house next to Friendship House last year. The Camerons often lead joint activities there.

The campus, with three buildings, a barn and a garden, cost about $1.5 million to build. Much of that was raised through partnerships with businesses and nonprofits. The land was given by Highland Presbyterian Church, which is located across the street.

The house is meant to attract those studying to be nurses, doctors, physician assistants, physical therapists and occupational therapists at four nearby universities and a community college. At full capacity, it will house 18 students and six people with developmental disabilities.

Each resident pays a monthly rent of $450, including utilities, and is provided a bedroom on a single-sex unit. Each unit includes a disabled person and three students.

But the students are not caretakers or babysitters. They are there mostly to offer social support.

"My job is to be a friend," said Victor Long, 30, who graduated from Campbell University's School of Osteopathic Medicine in May and shares a Friendship House apartment with Michael Brown, a 24-year-old man with autism.

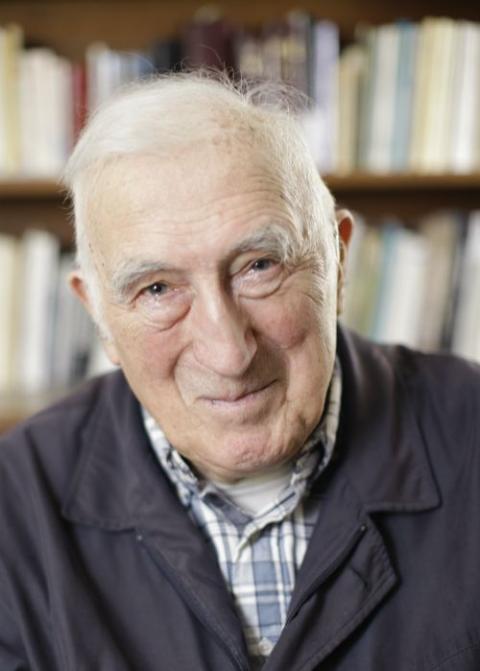

Jean Vanier (RNS/Courtesy of Templeton Prize/John Morrison)

"I go about my daily living. If I go grocery shopping or out to eat with friends, I try to get Michael involved, to be social," said Long, who begins a residency at Cape Fear Valley Medical Center in June.

That help with socialization is a key part of what draws people with disabilities to the house.

"Our son loves Friendship House and I think this is the first time in his life where he's felt like he has a network of friends," said Brenda Brown, Michael's mother. "That's probably the biggest thing he's gotten so far."

The first Friendship House opened in 2007 at Western Theological Seminary in Holland, Michigan, Matthew Floding, then dean of students, said a couple approached him at church and told him they wanted their disabled son to live independently but couldn't find a safe place for him.

At the time, the seminary was looking to provide more housing for its students, and the idea of pairing students with people with disabilities was born.

Floding, now director of ministerial formation at Duke Divinity School, said the need for housing may have sparked the project, but theological considerations also played a role. A co-housing arrangement would provide students entering ministry the opportunity to live among marginalized people — people like those Jesus ministered to.

"How can you train people to serve all people if you don't address it in your curriculum or experientially?" he asked.

Michael Brown, standing right, helps plant some raised beds at Friendship House in Fayetteville, North Carolina. (RNS/Courtesy of Avery Cameron)

An estimated 4.6 million Americans have an intellectual or developmental disability, according to The Arc, a national organization that advocates for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Developmental disabilities may include cerebral palsy, epilepsy, developmental delay, autism and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Intellectual disability generally means an IQ test score of approximately 70 or below.

Unlike L'Arche homes, which welcome people with profound disabilities (and also receive federal and state support), the adults with disabilities living in Friendship Houses typically have mild delays such as autism or Down syndrome. Most have high school diplomas and some hold driver's licenses.

Like at the L'Arche homes, faith binds the residents together. While no one has to profess a Christian faith, or any faith, residents are expected to participate in the weekly prayer service.

That was something Chasity Sullivan, 26, welcomed.

"I'm a Christian and had been looking for a church — and hadn't found the right one — and this offered a faith community," said Sullivan, who is studying at Methodist University to be a physician's assistant.

A prayer gathering of Friendship House in Fayetteville, North Carolina, Scott Cameron sits on the floor beside his dog. (RNS/Yonat Shimron)

Floding said he is interested in developing an interfaith Friendship House, perhaps on the campus of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. But for now, most of the interest has come from Christian seminaries: Princeton Theological Seminary, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and Luther Seminary are all considering opening their own Friendship Houses, he said.

For Cameron, who took his Friendship House residents on a hayride around town after prayer services on a recent Tuesday evening, it's a worthy effort.

"We need to be in community with folks who have disabilities more than they need to be with us," said Cameron. "There's something that they bring. It's a leveling effect, where ambition and the career ladder and your bank account balance, they become silly."

[Yonat Shimron is an RNS national reporter and senior editor.]