From left: Dorothy Gray, Joan Tillery and Gail Louis listen during a June 19 ceremony outside Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Washington, D.C., unveiling a plaque acknowledging "sins of racism" that took place there in the late 1800s and early 1900s that led Black parishioners to leave and establish a new parish nearby. Descendants of parishioners who left were present for a Mass and a ceremony and later spent time with modern-day Holy Trinity parishioners. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

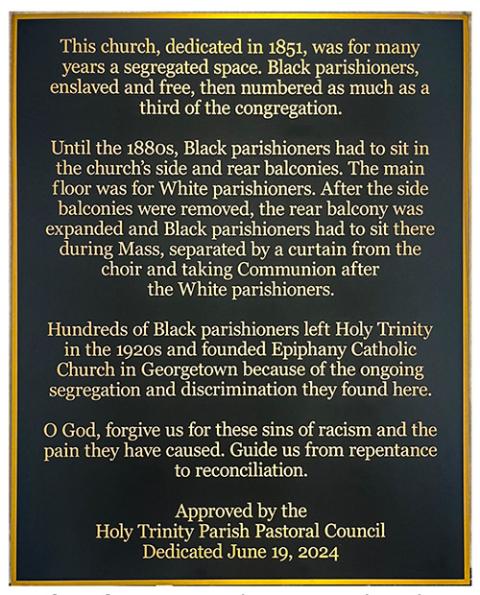

Not far from a plaque marking it as a place where the nation's first Catholic president worshiped, there's now a less auspicious marker outside Holy Trinity Catholic Church, in Washington's Georgetown neighborhood, recalling its past in the dark history of the country.

"Hundreds of Black parishioners left Holy Trinity," one of its four painful paragraphs explains, "because of the ongoing segregation and discrimination they found here."

On June 19, a descendant of one of those families helped unveil the marker, which also asks for forgiveness "for these sins of racism and the pain they have caused."

"This truth is ugly and painful," said Linda Gray, whose ancestors were among those who became part of Epiphany Catholic Church, the new parish Black families founded, also in Georgetown, after they left Trinity in the 1920s because of the racism they experienced there. "The truth hurts, it does, but the truth also has the power to heal."

On the steps of Trinity, Gray talked about how those who left did so "with no place to go," but with the promise that God would help.

Linda Gray, whose ancestors left Washington's Holy Trinity Catholic Church in the 1920s because of the segregation they experienced there, addresses a crowd that gathered June 19 to unveil a plaque outside the church acknowledging "sins of racism" at the parish. "The truth hurts, it does, but the truth also has the power to heal," Gray said. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

"There was no church structure to move into. It had to be built, and they had Mass wherever, in homes, in Black-owned businesses in Georgetown, anywhere but here," she said. "These are the people who believed that God would make a way out of no way."

Holy Trinity is the oldest Catholic parish in the District of Columbia. It was founded in 1787 and is located in one of the most affluent neighborhoods in Washington. The Jesuit parish boasts some notable churchgoers past and present, including President Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi, former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, as well as President John F. Kennedy and his family.

The marker says the modern church, dedicated in 1851, was "for many years" a segregated space. Though Black Catholics, "enslaved and free," were about a third of the congregation, they discovered they couldn't escape segregation even in a place that was supposed to be their spiritual home.

"Until the 1880s, Black parishioners had to sit in the church's side and rear balconies. The main floor was for White parishioners. After the side balconies were removed, the rear balcony was expanded and Black parishioners had to sit there during Mass, separated by a curtain from the choir and taking Communion after the White parishioners," the plaque reads.

Gray said that while she knew the "mechanics of the story," she wasn't aware of the details until coming into contact with members of Holy Trinity, who reached out to descendants of those who left.

It produced anger, disgust, shame and "a moment of what's so great about being Catholic?" she said. But she said she also realized that modern-day Trinity parishioners who approached the descendants also must have felt the same emotions, including embarrassment and shame, but had the courage to bring the truth out.

"My grandmother never discussed in detail what happened here," she told the crowd gathered. "We were past it, had our own, and we thrived as a church community for decades."

And if you looked at old parish photos, you wouldn't notice much of anything wrong, said Jesuit Fr. Kevin Gillespie, Trinity's pastor, during his homily at the church's chapel where he pointed out a mix of parishioners in front of the church in a black and white portrait.

"But when they walked in the church, they were segregated," he said. "That's what we recognize, is the sorrow and the pain."

Advertisement

He said he commended current parishioners for exploring the painful past and trying to find a way forward with descendants of "these brave men and women," the Black parishioners who left, who were willing to say: "This is not what we're taught by Christ, this separation, this segregation. We are calling prophetically to move and form a new community of faith."

The marker's unveiling on Juneteenth, which commemorates a day in 1865 on which the last of those who were enslaved in the U.S. learned they were free, made the day special for Gray.

"It is so meaningful that we celebrate the religious freedom of our Black ancestors on Juneteenth," she said.

Gillespie said he hoped it would open a wider dialogue about racism.

Sondra Raspberry bows her head in prayer during a June 19 ceremony outside Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Washington unveiling a plaque acknowledging the parish's history of segregation. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

"How can we speak to justice and the injustices of our day?" Gillespie asked. "We cannot do it alone. And so, we gather as family, friends, people journeying with our God ... as we go forward to a world where human beings are not separated but united. Let us continue to pray for this."

Gail Louis seemed visibly moved during Mass and at the marker's unveiling, thinking of those who had made a different life possible for her.

"It means so much to me," she told National Catholic Reporter. "I'm a fifth-generation Washingtonian and I wouldn't have even come to this area of town."

And yet she is a parishioner at Trinity, studied at nearby Georgetown University and is a founding member of the university's Black Alumni Council. When she was a member of the university's Board of Governors, she participated in the historic 2017 apology to the descendants of the 272 enslaved men, women and children sold in 1838 by the Jesuit province that administered the institution.

"It's like when we apologized to the 272," she said. "You know it's coming but when it actually comes, your heart is full. ... We have a lot of work to do and I don't mind that, but every now and then, it's nice to have a little moment of light."

As she contemplated the plaque, she said she had talked about it with her husband.

"It says everything that needs to be said, and then it asks for forgiveness — publicly," she said. "That's the important thing."

Laurice Redhead holds a photo of her grandmother during Mass at the Chapel of St. Ignatius at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Washington June 19, when current parishioners gathered with descendants of former Black parishioners who left the church in the 1920s because of segregation. (NCR photo/Rhina Guidos)

Laurice Redhead, a descendant of a former Black Trinity parishioner, told NCR it was important to hear what others had to say in order to forgive and move forward. The plaque, the discussion, made her feel as if "we're moving [toward] something much better."

She took a framed photo of her grandmother, elegant in a black dress with white polka dots, to the Mass before the commemoration of the plaque. She said she wanted her grandmother, who was married at Holy Trinity but was part of the families that left, to hear what was being said. Gillespie took the photo, and placed it on the altar after Mass so others could appreciate it.

"I wanted her to be present and that's the closest thing I could bring," she said. "And I felt her when we put her on the altar, and said 'You go, girl. You're here.' "