(Melissa Cedillo)

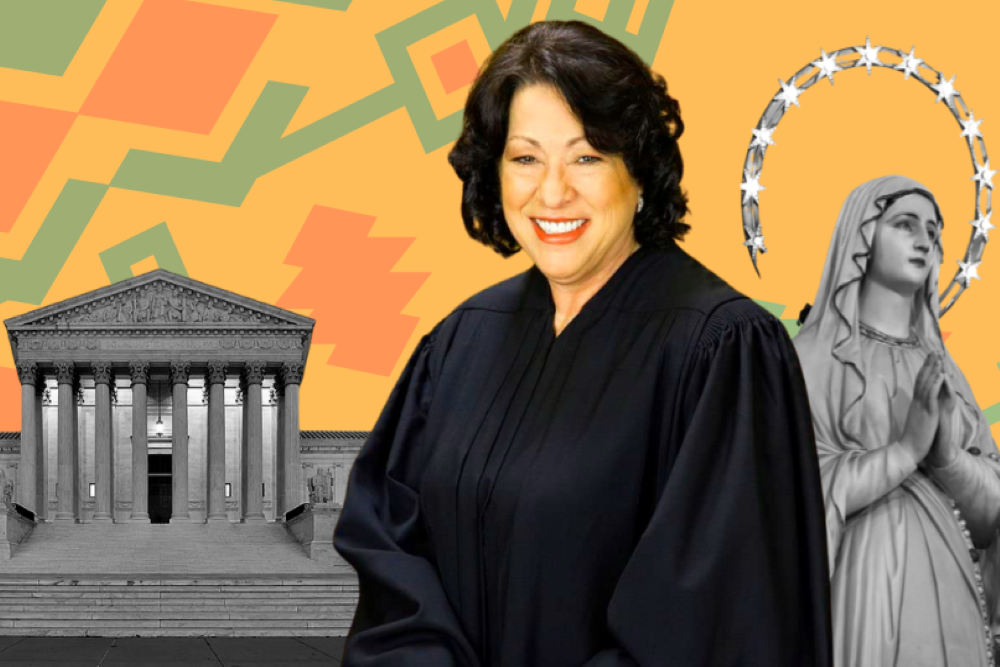

For some Latinas who study and practice law, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the first Latina on the court, is a hero. Now, as the court considers a high-profile case that could overturn Roe v. Wade, Sotomayor's dissent has become a symbol of the Latinx community's complicated relationship with the U.S. Catholic Church.

According to statistics from the Hispanic National Bar Association, only 4% of U.S. lawyers are Hispanic, despite making up 18% of the population. An even smaller number, 2%, are Latina.

Tatiana Estrada, a second-year law student at Loyola Law School, found Sotomayor's elevation to the nation's highest court inspirational. "Going into a profession where I know I'm significantly underrepresented, it was really admirable and inspiring to see someone who looked like me reaching such a high level," she told NCR.

Sotomayor is one of six Catholics on the current court. Amy Coney Barrett, a Catholic who opposes legal abortion, has spoken publicly about how her faith shaped her beliefs. But for some young Latinas with aspirations in the legal profession, Sotomayor's upbringing and the way she navigates her role on the Supreme Court resonates on immigration and other issues.

Priscilla Higuera, an attorney in California, remembers how excited she was when Sotomayor was nominated to the Supreme Court in 2009. "Her childhood neighborhood looked a lot like mine," Higuera told NCR.

U.S. Supreme Court nominee Judge Sonia Sotomayor is sworn in as an associate justice by Chief Justice John G. Roberts in Washington Aug. 8, 2009. She is the first Latina to serve on the Supreme Court. (CNS/Reuters/Jim Young)

Sotomayor is Puerto Rican and was born and raised in the Bronx, New York. She was raised Catholic and attended Catholic schools: Blessed Sacrament elementary school, which has since closed, and Cardinal Spellman High School. Sotomayor recalls her mother working long hours so she could attend such schools.

Since she has been on the Supreme Court, she has described herself as someone who might not be traditional, but that she is spiritual. She added that she believes in God and in the Ten Commandments.

Estrada has been a fan of Sotomayor since she was 14. Similar to Sotomayor, Estrada knew she wanted to be a lawyer from a young age. Like the justice, Estrada also struggled with the standardized testing required for the law school admissions process. Sotomayor has spoken on the "cultural biases" against communities of color that can be built into standardized testing, making it harder for groups like the Latinx community to attend law school.

Estrada decided to become an immigration attorney after attending an immigration rights rally in Los Angeles in 2006. "I was about 9 or 10 years old, and it was my first time really seeing immigrant advocacy work," she told NCR.

But immigration is also personal for her. Estrada's family immigrated to the United States from Mexico. "I was raised within the immigrant community. Most of my family are immigrants," Estrada explained, "and a lot of their friends are immigrants."

"It was inspiring to see someone who looked like me reaching such a high level," Tatiana Estrada, a student at Loyola Law School, said of Sonia Sotomayor. (Courtesy of Tatiana Estrada)

She said immigration status make it difficult for many in her community to access housing, health care and employment. "I saw how immigration law not only affected the immigrant individual themselves, but how it affected the family unit," she said.

Estrada's Catholic upbringing also informs her perspective on law. "I was raised in the Catholic church, I've done all the sacraments, I go to church," she said. "I believe in God, but at the end of the day the foundation of our legal system is to separate church and state."

Some Catholic Latinas, though, find Sotomayor's appointment to the court "an appeal to identity politics."

"The fact that someone is Latino to me, that fact alone, doesn't say anything about a person," Ligia Castaldi, a professor at Ave Maria School of Law, told NCR. “That doesn’t tell me their legal philosophy … or whether someone will promote an appropriate interpretation of the Constitution.”

A native of Honduras, Castaldi said her faith pushed her to focus on bioethics, international law, international human rights law and prenatal rights.

Castaldi believes that an important American heritage of a colorblind constitution is being undermined by justices on the court. "Now there are at least certain justices, including Justice Sotomayor, who are promoting not color blindness, but color consciousness," she said.

"They believe that rather than be blind on race, we need to be overly conscious of issues like race or color that should determine certain public policy outcomes and I think I don't subscribe to that ideology," she added.

Ligia Castaldi, a professor at Ave Maria School of Law, greets Pope Francis. She said her faith pushed her to focus on bioethics, international law, international human rights law and prenatal rights. (Courtesy of Ligia Castaldi)

Sotomayor's dissents and oral argument

Catholics who oppose legal abortion disagree with Sotomayor's support for abortion rights. But her recent dissent in the Supreme Court ruling upholding Texas' new abortion law and her pointed questions during oral arguments in the Mississippi case raised issues of the role of religion in pluralistic society, the reputation of the court and the impact on women living in poverty.

In those cases, Sotomayor expressed concern over religious beliefs, the reputation of the court and the impact on women living in poverty.

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization involves the Mississippi law that would ban most abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy and could overturn Roe v. Wade. During Dec. 1, 2021, oral arguments, Sotomayor challenged Mississippi Solicitor General Scott G. Stewart's description of when life begins.

"How is your interest anything but a religious view?" Sotomayor asked. "The issue of when life begins has been hotly debated by philosophers since the beginning of time. It's still debated in religion. So, when you say this is the only right that takes away from the state the ability to protect a life, that's a religious view, isn't it?”

Sotomayor also cited Mississippi poverty statistics in her arguments,

"So when does the life of a woman and putting her at risk enter the calculus? Meaning, right now, forcing women who are poor — and that's 75% of the population and much higher percentage of those women in Mississippi who elect abortions before viability — they are put at a tremendously greater risk of medical complications and ending their life, 14 times greater to give birth to a child full term, than it is to have an abortion before viability," she said.

"And now the state is saying to these women, we can choose not only to physically complicate your existence, put you at medical risk, make you poorer by the choice because we believe what?" she continued.

Advertisement

According to a 2014 Pew Research Center study, Mississippi's population is about 4% Catholic. The most recent U.S. Census data indicates that about 3% of the population is Hispanic.

Sotomayor was one of four judges to write a dissent to the September 2021 court ruling that upheld the Texas abortion law.

"The Court's order is stunning," she wrote. "Presented with an application to enjoin a flagrantly unconstitutional law engineered to prohibit women from exercising their constitutional rights and evade judicial scrutiny, a majority of Justices have opted to bury their heads in the sand."

For Marissa Nuñez, an immigration advocate and graduate student in public affairs at the University of Texas at Austin, Sotomayor "provides a powerful example of how to challenge norms within Latinidad and cultural Catholicism."

"Her dissent proves that one is not sacrificing their identity by standing up for what is just, and opens the door for Latinxs and cultural Catholics to engage in dialogue about how our cultural views should shift to guarantee rights for all," Nuñez told NCR.

Born and raised in the border town of El Paso, Texas, Nuñez previously worked at Innovation Law Lab and hopes to research labor policy and work with folks who are fighting for better wages, work conditions, and workplaces.

Nuñez said Sotomayor's dissents often consider the impact on undocumented people.

For Higuera, Sotomayor's dissents on the abortion cases illustrate a woman fighting for her community on the nation’s highest court.

"She essentially used her voice and her dissent to create a record of public shaming," Higuera said. "It will forever be in the record."

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor hugs her mother, Celina Sotomayor, after her investiture ceremony at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., Sept. 8, 2009. (CNS/Bob Roller)

In Texas, the Latino population is much larger than in Mississippi. According to the 2020 census, the state has more than 11 million Latinos, which grew by almost 2 million since 2010. Over a decade ago, the 2010 census found almost 40% of Texans identified as Latino — the group with the largest population in the state in 2021.

More than 70% of Catholics in Texas also identify as Latino, according to a 2014 Pew Research Center report.

Some Latinas point out that Sotomayor's dissents do not align with Catholic teaching.

When Sotomayor was first nominated, Lucia Baez Luzondo, a native of Puerto Rico, remembers a sense of pride.

"But then, as I saw her operate, it was no longer a sense of pride, but a sense of disappointment," said Luzondo, an attorney at Luzondo Legal.

She views Sotomayor as a "judicial activist" who "stretches fact and truth to the extreme."

As an attorney, a woman, a mother and a Catholic, Luzondo considers Sotomayor's dissents on cases involving abortion and gender "antithetical to the Gospel" and "embarrassing."

Luzondo, who works in immigration law, says she works toward upholding the dignity of every human being and the common good in her practice. "Between the polarization and the institutional church," she said she started her practice because of, "the absolute need for decent expert representation and immigration for these beautiful folks."

Sonia Sotomayor, then a federal appeals court judge, chats with students at her alma mater, Cardinal Spellman High School in the Bronx section of New York, in this undated photo released by the White House in 2009. (CNS/Reuters/White House handout)

Sotomayor's background

Some have attributed Sotomayor's low-income, first-generation background as emblematic of the American dream and formative to her perspectives on the court.

Sotomayor's parents came to New York from Puerto Rico, raising Sotomayor in the housing projects of the South Bronx. Sotomayor has said that her eight years at Blessed Sacrament were formative to her achievements. And while she has mixed memories and feelings about the school overall, she does recall that the school stepped in to assist her family after her father died when she was 9.

A combination of her father's death and her mother's dedication to improve her children's lives led Sotomayor to set her goals by the end of 8th grade. Sotomayor told her teacher, Sr. Mary Regina, that she wanted to become "an attorney and someday marry."

She would go on to graduate from Princeton University and Yale Law School.

After law school, Sotomayor served as an assistant district attorney in Manhattan. She also served alongside Jesuit Fr. Joseph O'Hare, the retired president of Fordham University, on a New York City campaign finance review council. She went on to work at the federal level and eventually the court of appeals.

Sotomayor became the youngest judge in the Southern District, the first Hispanic federal judge in New York state and the first Puerto Rican female judge in a U.S. federal court. She was appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2009 by President Barack Obama.

Higuera had just graduated from college when Sotomayor was appointed to the Supreme Court. Everything from the justice's first name to her background resonated with her.

Higuera's first experience with the law came when she was about 8, when her father was incarcerated and, upon release, deported. Higuera learned at a young age the power the judges and attorneys hold over immigrant families. The experience inspired her to pursue a career in law.

"I wanted to be a player in the legal realm," she said. "And I wanted to dedicate my career and my life to helping people that are in similar situations."

Higuera is now a deportation defense attorney at her own practice in San Diego.

Like Sotomayor, Higuera was raised Catholic and believes in God and her rosary, even if she does not go to Mass as often as she would like. As someone from an immigrant family, Higuera says that she was taught to love the U.S. for its freedoms, but rulings in cases like the Texas abortion law have her questioning this belief.

"It's a hard balance to grow up in that fairy tale of the land of the free and get a rude awakening to learn that if you're a woman, an immigrant, and/or a person of color that those freedoms can be taken away," she said.