Crew members prepare May 14, 2013, to launch an X-47B pilot-less drone combat aircraft for the first time off an aircraft carrier, the USS George H. W. Bush in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Virginia. Pope Francis, in his 2020 encyclical Fratelli Tutti, significantly shifted the Catholic Church's teaching on the use of military force. (CNS/Reuters/Jason Reed)

Pope Francis significantly shifted the Catholic Church's teaching on the use of military force in 2020, declaring in the encyclical Fratelli Tutti that because of the brutality of modern combat it is now "very difficult" for countries to invoke the just war theory in pursuing violent conflict.

Catholic peace activists at the time hailed the move, calling it an historic development in church teaching that could undercut efforts by national leaders to legitimize their uses of military force.

Reviewing the document a year later, instructors at U.S. military academies did not quite agree with the activists' assessment. But some did concur that Francis had adjusted church teaching in a real way.

U.S. Army Lt. Col. Stephen Woodside, an English and philosophy professor at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, described Fratelli Tutti as "an interesting document, open to some interpretation" on just war theory.

"On one extreme, the pope could be seen to say that there is just no such thing as a just war, that war is never justified. I don't read him that way," said Woodside, who told NCR that he understands Francis rather saying that it is "highly unlikely" that modern warfare can be morally justified because of modern weaponry and the disastrous toll combat inflicts on civilians.

"It does still seem to be a change of direction from the church at least," Woodside said.

Pope Francis prays in the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery in Nettuno, Italy, Nov. 2, 2017, the feast of All Souls. The cemetery is the resting place of 7,860 American military members who died in World War II. (CNS/Paul Haring)

U.S. Air Force Col. James Cook, the head of the philosophy department at the U.S. Air Force academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado, said Fratelli Tutti "abhors war and yet it does leave the door open" for military action.

"The language is quite strong," said Cook, who reads the pope's words in Paragraph 258 of the encyclical that "it is very difficult nowadays to invoke the rational criteria [for just war] elaborated in earlier centuries" as evidence that Francis still holds out the possibility that combat can be morally justified.

"That's why I call this encyclical a tightrope walk," Cook said.

Fratelli Tutti, released on Oct. 4, 2020, is the third encyclical of Francis' eight-year papacy. A wide-ranging letter, the encyclical lays out a vision for the how the world might change after the coronavirus pandemic, reflects on efforts for Christian-Muslim dialogue and articulates some of the pope's social philosophy.

In the view of some scholars and peace activists, the encyclical's focus on just war teaching reflected the idea that modern combat has made the teaching obsolete.

"Too often, our tradition has been turned against us. It's really fraudulently been used to justify the unjustifiable," said Maryann Cusimano Love, a professor of international relations at the Catholic University of America who studies issues related to just war and just peace.

In recent years, the Vatican's Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development and the international Catholic peace movement Pax Christi have hosted joint conferences in Rome where speakers have argued that just war theory has been abused and stretched to the breaking point.

"The fact is that the wars on the planet today are not just wars, from Syria, to Afghanistan to Yemen to Somalia," Love told NCR. "While we can imagine a just war in theory, in practice we don't see just war."

In his 2017 World Day of Peace message, Francis said that nonviolence "is sometimes taken to mean surrender, lack of involvement and passivity," but added that that is "not the case." The pope argued that "countering violence with violence leads at best to forced migrations and enormous suffering," because vast resources are spent on military ends instead of humanitarian needs. At worst, Francis said, violence "can lead to the death, physical and spiritual, of many people, if not of all."

Just war theory, first articulated by St. Augustine of Hippo nearly 1,600 years ago, widely holds that military combat can be squared with the Gospel if the cause is just and the fighting is waged in a restrained manner that protects noncombatants.

U.S. Air Force Col. James Cook, the head of the philosophy department at the U.S. Air Force Academy, and U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Shawn McKelvy, who teaches on the law of armed conflict at the U.S. Air Force Academy (Courtesy of U.S. Air Force Academy)

Cook, at the Air Force Academy, said his institute's curriculum "owes a great deal" to Catholic writers like Augustine, St. Ambrose of Milan and St. Thomas Aquinas. "I could name many more," he said.

In one section in Fratelli Tutti, subtitled "The Injustice of War," Francis examines warfare with a jaundiced eye, calling it "a failure of politics and of humanity" that "leaves our world worse than it was before." He describes war as "the negation of all rights and a dramatic assault on the environment."

Francis also questions whether the development of nuclear, chemical and biological weapons, and advanced technology, have granted war "an uncontrollable destructive power over great numbers of innocent civilians."

Love said Francis is showing "we can no longer think of war as a solution because its risks will probably always be greater than its supposed benefit."

C. Anthony Pfaff, a professor at the U.S. Army War College's Strategic Studies Institute in Carlisle, Pennsylvania (Courtesy of C. Anthony Pfaff)

"He's making the present and forward-leaning argument that in our own times, the mechanisms of war are far too destructive to ever be proportionate, to ever meet that criteria," she said.

But in a military academic setting, to speak of just war as an oxymoron would be to present pacifism as an alternative, said C. Anthony Pfaff, a professor at the U.S. Army War College's Strategic Studies Institute in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

"There's no approach that includes pacifism that can't be abused and exploited by people for their own unjust ends," said Pfaff, who served on the U.S. National Security Council staff and on the policy planning staff at the U.S. State Department during the Obama Administration.

Pfaff told NCR that just war principles have informed international law, so advocates for "just peace" or nonviolent solutions need "to be careful about throwing out the baby with the bath water."

Said Pfaff: "When the pope makes the point about let's prioritize the rule of law, international law and the ability of [supranational organizations like the United Nations] to adjudicate conflicts before they get to war, the just war theory informs all of that."

Pfaff also interprets Fratelli Tutti as reflecting the idea that military power should be used to protect "human security" — the rights of people to be free from fear and want of basic necessities for a life of dignity, instead of being deployed for national security interests.

Sean Chambers, an ethics and sociology professor at Valley Forge Military College in Wayne, Pennsylvania (Courtesy of Sean Chambers)

Sean Chambers, an ethics and sociology professor at Valley Forge Military College in Wayne, Pennsylvania, reads the document through a similar lens.

"The pope's [encyclical] last year has been, as I read it, to encourage nations to really look at strategies to achieve a just peace instead of using just war theory to justify going to war," said Chambers, who teaches on the just war tradition.

Chambers told NCR that Fratelli Tutti challenges political leaders to exhaust all non-military means of resolving international conflicts before resorting to armed conflict, which is a traditional principle in just war theory.

"I think the pope is asking the stronger military nations to look seriously at diplomacy and stepping up their use of it," he said.

U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Shawn McKelvy, who teaches on the law of armed conflict at the U.S. Air Force Academy, told NCR that he sees Francis' aspirations for peace and nonviolence in Fratelli Tutti as similar to how the international community tried to curb aggressive warfare after two destructive world wars in the 20th century.

"From a legal perspective, where the international community has come together in ways to try to at least limit war, what I think the pope is doing in some ways here is aspirational in trying to suggest that there are better ways," McKelvy said.

Advertisement

While recognizing Francis' concerns over nuclear, chemical and biological weapons — the latter two categories are categorically banned in international law — military instructors who teach ethics and just war theory to cadets and senior military officers critiqued the pope's words on new battlefield technologies.

"I'm not as down on the technology part because there's a good argument to be made that with increased technology … it can offer a more precise way to wage war, which I'm inclined to think might be able to reduce civilian casualties," said Woodside, the West Point professor.

"I think the crux of the issue is that if war is waged, it's almost inevitable that innocent people are going to be killed, and that's very regrettable," Woodside added.

Cook also argued that "modern weaponry" includes weapons such as cyber and kinetic weapons that he said are more discriminate and less violent. He also said traditional just war theory has not emphasized the means of achieving military ends as much as it has the intentions and the aftereffects of military combat.

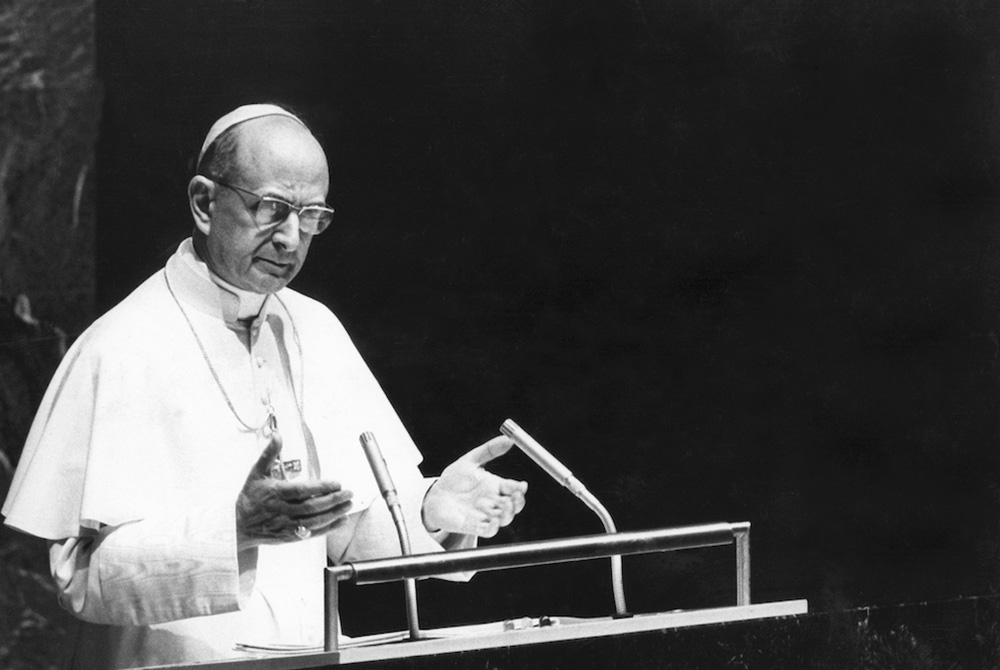

Pope Paul VI makes a special appeal for world peace in 1965 at the United Nations headquarters in New York. "Never again war!" he declared to the General Assembly. (CNS/United Nations/Yutaka Nagata)

"One of the things we find is that the entire tradition of just war thought is about minimizing the frequency of wars, and then minimizing the suffering in the sad event that war does occur," Cook said. "We place ourselves between pacifism in this sense, on one hand, and nihilism on the other."

In Fratelli Tutti, even if he leaves some wiggle room by not ruling out completely the possibility of just war, Francis echoes his predecessors when he repeats the famous refrain from Pope Paul VI's 1965 speech to the United Nations: "Never again war!"

"There's a tension there, and it's not a bad tension," Cook said. "It's absolutely fine, I think, to have in the same document an aspiration never to have war. But until the pope goes so far as to say that it's impossible in our modern era for the rational criteria of the just war tradition to be met, until he says that, we can't call ourselves pacifists. At least that's my view."