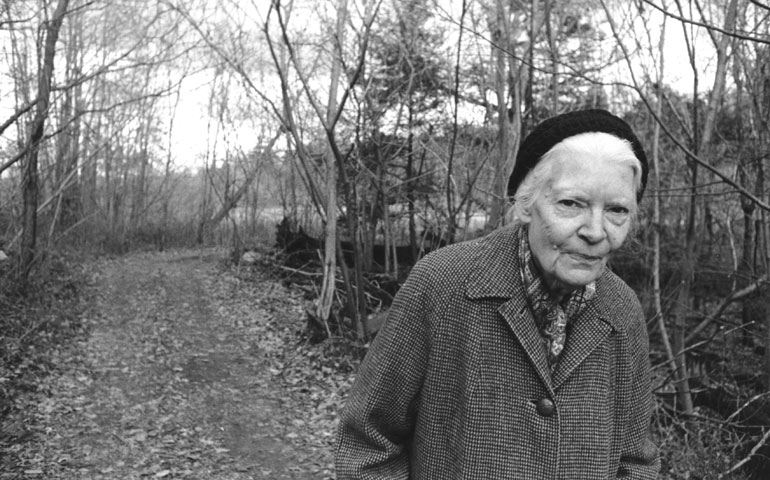

Dorothy Day at the Catholic Worker farm in Tivoli, N.Y., in 1970 (Bob Fitch Photo Archive © Stanford University Libraries)

During a recent roundtable discussion at an urban house of hospitality, in which we dealt with questions of corporate agriculture, genetically modified organisms, and food justice, one longtime Catholic Worker noted with some exasperation the "overemphasis" on the environment.

"We may recall that there was a woman named Dorothy Day after all," he commented sarcastically. The implication was clear: Don't forget that it was Day who founded this movement, and her concern was primarily, perhaps exclusively, the urban poor who populated the houses of hospitality.

Such a perception of Day's role in the movement persists. Day, it is commonly thought, was the city girl who never quite understood the zeal for the land that characterized the quirky French peasant Peter Maurin.

For the first several years of my life as a Catholic Worker, I too shared in this misleading dichotomy. As my work and interest drifted from city hospitality to life on a Catholic Worker farm, I turned to Maurin and his watchwords of "cult, culture and cultivation." But in the last few years, as I have reread Day's works, I now see her in a new, fuller light.

The increased likelihood of Day's canonization has spurred a bevy of discussion about her. Champion of the poor, stalwart of pacifism, devotee of voluntary poverty, and radical journalist: These are all frequently -- and justly -- invoked to describe Day.

But to capture more fully the force of her life, vision, and voice for our age -- one in which ecological devastation threatens existence -- it is essential that we seek beyond the usual platitudes. Crucially, Day was a lover of God's creation, an agrarian who believed we must all find our way to a healthier relationship with the soil. Decades before the emergence of the environmentalist movement, it was she, among few others, who called for a land- and craft-based society.

After a wayward upbringing marked by moves from city to city, Day eventually landed, in her 20s, on Staten Island, N.Y., where she fell in with a bohemian, literary crowd. This circle of writers and artists were discussing, in addition to anarchism and distributism, an "emerging philosophy of the yeoman farmer, whose simple, self-sufficient life was grounded in a sense of place and responsibility to other," wrote Paul Elie in The Life You Save May Be Your Own.

Renting a cottage on the beach, Day encountered peace and happiness for the first time in the fields and forest. Amid the raw air of the country, she found a strong appetite for prayer. She wrote articles on gardening for local papers, and, with the help of her partner, Forster Batterham, she started a garden. In the fall of 1925, Day wrote to Forster from Florida, expressing her anxiety to get back to Staten Island in order to put manure on the garden. "It may be a sentimental notion," she wrote, "but I think it would be wonderful to live entirely off the land and not depend on wages for a livelihood."

Nevertheless, Day was indeed skeptical of Maurin's belief that going back to the land was the keystone for reconstructing the social order. Though she knew the satisfactions of eating a vegetable she had cultivated herself, it was still the city she knew best. It was there where the vast majority of the unemployed resided.

Gradually, however, she "came to see what he was talking about." She admitted that the houses of hospitality and soup lines were only a half step toward their vision. The farms were "the real step," she wrote; she and Maurin were hoping that Maryfarm, the community they started in northeast Pennsylvania in 1936, would become the permanent piece of their green revolution -- what she called "the heart of the work."

Integral to her grasp of Maurin's agrarianism lay with her first real encounters with the agricultural world. A few months before their first farming venture began, she toured the South, observing farms and talking with laborers in an effort to organize tenant farmers. At a stop outside Memphis, she reacquainted herself with Allen Tate, well-known "Southern Agrarian" and former comrade from her bohemian days. He marveled at her energy and practical sense; she had what he called "a fanatical devotion to the land."

On a tour through the Northwest, she noted in her diary her realization of the agricultural "wastelands" of the "industrial, factory system of farming." In the early 1940s, during a two-week class held at the Grail, a lay community of women in Ohio, she learned crafts and culinary skills. "We have learned to meditate and bake bread," she gushed, "pray and extract honey, sing and make butter, cheese, cider, wine, and sauerkraut."

Back home, she was never able to dwell on the land as much as she wanted -- "I have long since 'given up,' 'offered up,' the field, for the city slums," she wrote in her diary. As much as Day loved farm life, she felt obliged to make sure the house of hospitality in the city remained a refuge for the poor. It was clear that she saw herself in the vein of Dominican Fr. Vincent McNabb, a radical agrarian from across the Atlantic, whom she quoted as responding to the question of why he remained in London: "To get people out of here."

But she did, as much as she could, luxuriate in farm life. Besides practicing crafts like sewing, knitting and weaving, she canned tomatoes, fed chickens and pigs, learned about cows, weeded the garden and hauled water. She reflected in her journal that in the country, "with growing things, one has the sacramental view of life."

Although most Catholics did not live on the land, she was encouraged by her daughter's decade-long homesteading efforts.

"If we who are tied to the city cannot go villageward at once, we can begin to hold it as an ideal for our children, and begin to educate them towards it," she wrote during one stint on her daughter's homestead.

"I still think that the only solution is the land," Day wrote in 1957, more than two decades after the start of the first farming venture. She had become the voice for Catholic agrarianism. "How can we teach our children about creation and creator when there are only man-made streets about. How about life and death and resurrection unless they see the seed fall into the ground and die and yet bring forth fruit."

The supernatural and natural easily commingled within her sacramental sensibility. She knew that one could not flee God's good earth to find the divine: It is the "physical things," she insisted, that testify to the goodness of the Lord.

As Day aged, opportunities arose for her to spend more and more time on the farm.

Her passion for justice on the land later in life, moreover, shaped her visit to California in 1973. There, in solidarity with striking farmworkers, she was arrested for an act of civil disobedience. Even in her last year, she still rejoiced in her diary in the "little patches of green pushing out thru cracks in the sidewalk."

Here on our Catholic Worker farm in the springtime, as the mud gradually stiffens and wild greens emerge before the planted crops, I like to remember Day walking each day to early morning Mass, eyes fixed on the sidewalks of lower Manhattan, looking "with longing eye," as she wrote in Loaves and Fishes, for the delicious edible weed known as lamb's quarters.

For nearly five decades, Day remained an important and clear voice of hope for God's beautiful world. She belongs in the company of those today calling our attention to the land, to its sacramentality, to its vulnerability in the face of the destructive whims of industrial civilization. It is vital that her words and witness reverberate throughout our church and in our culture:

In spite of the nuclear age we are living in, we can plant our gardens even if they are only window boxes, we can awaken ourselves to God's good earth and in little ways start going out on pilgrimage, to the suburbs, to the country, and when we get the grace, we may so put off the old man, and put on Christ, that we will begin to do without all that the City of Man offers us, and build up the farming commune, the village, the City of God wherein justice dwelleth.

[Eric Anglada is a member of New Hope Catholic Worker farm in Iowa.]