The campus of The Catholic University of America is seen from the bell tower of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington. (CNS/Bob Roller)

The path of the Catholic Church's social justice teaching normally weaves through places like soup kitchens and refugee centers, settling often among society's poor and marginalized, far from the centers of commerce and power. But a luxury suite version of the teaching was under construction recently, during a three-day conference at the Catholic University of America.

The talk was all about money — good money — in the form of "Good Profit," the theme of the Oct. 4-6 gathering co-sponsored by the university's Busch School of Business and Economics and the Napa Institute, whose chairman and co-founder, Timothy Busch, is the one whose name is attached to the business school. More than 500 people were registered for the event.

The event's high point came on the second day with a rare public appearance by Charles Koch, a major funder of the business school and outspoken libertarian who has developed a trademarked business philosophy called Market-Based Management. He also has written two books, one of which, Good Profit: How Creating Value for Others Built One of the World's Most Successful Companies, lent the gathering its theme and focus.

The university has taken its fair share of criticism from some quarters for accepting money from the Charles Koch Foundation. In recent years, the business school has received a total of $47 million in gifts, including $15 million from the Busch family and $10 million from the Charles Koch Foundation. The rest came from four other donors.

The Koch brothers, who have donated huge sums to the arts and museums, also heavily fund conservative political causes, tea party candidates, and organizations that advance libertarian ideology. While it is difficult to pin them ideologically on a number of issues, they are extremely conservative on issues of economics and the marketplace. Charles' brother, David, confirmed in an 2014 interview with Barbara Walters that he supports gay rights and a woman's right to choose, views that his brother, Charles, "seemingly shares" according to author Daniel Schulman, who has written a biography about the Kochs.

But the markedly conservative Catholic crowd attending the Good Profit conference seemed unconcerned about politics and hot-button issues. The discussion primarily focused on the nobility of creating profit for the benefit of individuals and society, providing workers with purpose and "principled entrepreneurship." Issues such as poverty, income disparity, consumer protections and workers' rights or what might be done about unprincipled entrepreneurship rarely disturbed the discussions primarily absorbed with keeping business prerogatives free from government controls.

But that question about why Catholic University would be staging such a conference was the first out of the gate in a leadoff presentation by Andreas Widmer, a familiar business figure of the Catholic right and co-founder and director of the Art & Carlyse Ciocca Center for Principled Entrepreneurship at the Busch School.

"So you ask yourself 'what's a nice Catholic university like ours doing discussing profit in the first place? Have we stumbled off the narrow way of discipleship on to the wide way of the prosperity gospel?' "

—Andreas Widmer

Why this discussion?

"We Christians have a natural suspicion of profit," Widmer said. "Maybe it's because of its association with self-interest. Disciples are called to follow the Master on the path of self-gift and sacrifice to others. And we know that we cannot serve both God and mammon. So you ask yourself 'what's a nice Catholic university like ours doing discussing profit in the first place? Have we stumbled off the narrow way of discipleship on to the wide way of the prosperity gospel?' "

His short answer was, "No, we have not," but what followed was not a further explanation of that answer, but rather a bit of philosophically tinged anthropology and exegesis that views God, by virtue of the act of creation, as a worker. Humans' "dominion over nature and the command to be fruitful and multiply came before the Fall," he said, so "work is not a punishment but a call to perfection and an opportunity to participate in the creativity of God himself."

Business, Widmer said, is a form of work. "We are called to create something out of nothing, if you will, to create valuable goods and services based on an idea sparked in our minds and carried out in the imagination" and in collaboration with others. Profit is not just the accumulation of wealth, but "includes many dimensions of human flourishing."

Embedded in his optimism about free markets was a conference-wide presumption that the most wealth and the most good for the most people would only occur if business were free of all national government and international regulations and interference.

Shanker Singham, a resident of the United Kingdom who heads up the Legatum Institute's Special Trade Commission and the institute's work on the "economics of prosperity," described the successes of the market system as the degree to which it has fostered open trade and the protection of property rights. Its failure was seen in any acquiescence to "cronyism" in the form of taking government grants or subsidies, or to "government regulatory systems."

He said he disliked the term "capitalism," which "is really not what we're about. What we are about is voluntary exchange without distortion," a word he used to describe government interference of any sort.

Advertisement

The popes speak

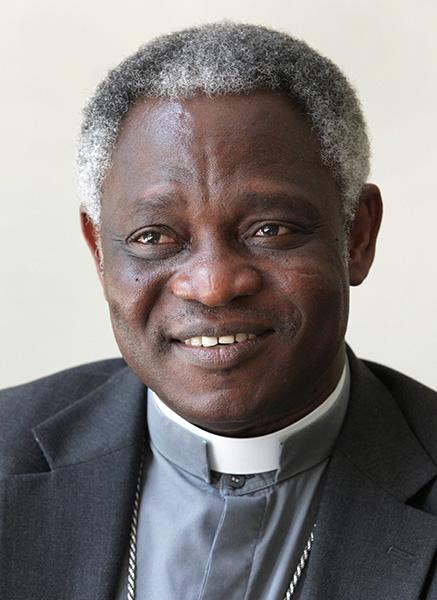

A second-day appearance by Cardinal Peter Turkson, appointed the first prefect of the new Vatican Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, provided a finger on the scale of the other side of such idealistic views of an unrestrained free market. His presentation, which immediately preceded that of Koch, was heavily laced with concern for workers and cautions about the excesses and dangers of the marketplace.

Cardinal Peter Turkson, prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development, is seen in this 2011 file photo. (CNS/Bob Roller)

The cardinal began with a "preamble" that ranged through papal teaching on social justice themes from the seminal 1891 encyclical of Pope Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, which examined the condition of poor workers in increasingly industrialized countries. According to Turkson, the important measure of profit to Leo XIII "was not the quantity but the quality of profit."

Pope Pius XI, who reigned during the 1930s and the period of the Great Depression, "warned against the evils of economic dictatorship and of a totally unregulated market economy," said Turkson. Pius also "invoked what would become known as the concept of the just wage."

Pope Paul VI, in his 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio, wrote that "it is unfortunate that on these new conditions of society a system has been constructed which considers profit as the key motive for economic progress, competition as the supreme law of economics, and private ownership of the means of production as an absolute right that has no limits and carries no corresponding social obligation." The new conditions, he said, produced "the international imperialism of money."

Twenty years later, in his encyclical Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, Pope John Paul II raised concern that "the desire for profit and the thirst for power" hindered social development, said Turkson. "Pope John Paul II believed that in a different world, ruled by concern for the common good of all humanity or by concern for the spiritual and human development of all, instead of by the quest for individual profit, peace would be possible as the results of the more perfect justice among people," he said.

Pope Benedict XVI, said Turkson, "suggests the need to create space within the market for economic activity carried out by subjects who fully choose to act according to principles other than those of pure profit without sacrificing the production of economic value in the process."

Finally, he said, Pope Francis warns against the idolatry of money and the existing economic system, "saying that such a system tends to devour everything that gets in its way in the pursuit of increased profits." In its path, anything that "is fragile — like the environment or the poor, becomes defenseless before the interests of a deified market, which becomes the only rule."

Good profit, continued Turkson, accrues to good people in good companies making good goods and services for the common good. He said he has encountered business people who "know deep down that, as good stewards of the world, they should go the extra mile to undo mistakes of the past, supporting sustainable businesses that can restore the balance of nature and leave the world in a better state than they have found it."

"We have to discern and reconcile," said Busch, in remarks that bridged Turkson's appearance, his fourth at Napa gatherings, and that of Koch. "We have to listen to both sides," Busch said, an acknowledgement of the tension between much of what Turkson offered and many of the other presentations.

Koch and creating value

The 81-year-old Koch has led Wichita-based Koch Industries since 1967 to its current status as the second largest private company in the United States. His personal worth is more than $47 billion. Interviewed onstage by Widmer, Koch said he was inspired by "the philosophy that to whom much is given much is expected." He said he "grew up having every advantage. As a kid, I didn't always have this attitude."

But by the time he started in business, that sense of privilege resulted in a deep sense of obligation. "I've been given all this and people have put up with a lot dealing with me as I was growing up because I challenged everything. I wanted to do things differently. I wanted to be different. So, I felt a real obligation to make a contribution, to make a difference, and I knew I wasn't smart enough to figure out how to do that by myself."

The creation of value to help others is the central tenet of Koch's program, but it grows not out of altruism for its own sake, but out of self-interest.

He had been smart enough to earn an undergraduate and two engineering degrees from MIT before taking over the family business. He said he "internalized Newton's insight — 'If I am seeing further it's because I am standing on the shoulders of giants' " — and went looking for the giants in the areas of scientific and social progress. He began studying everything he considered relevant, across multiple disciplines. He said he discovered principles that he began to apply to all areas of his life — business, family, community and charitable activities.

He came upon the realization that common people, who had achieved little advancement over millennia, began to find new opportunity in different parts of the world beginning in the mid-18th century as "the common person began to be given equality under the law and social dignity."

Economist Joseph Alois Schumpeter’s ideas about "creative destruction" taught him that a business could not remain static, that a competitor would always be figuring out new innovations to better products and processes. He concluded, "If you just continue to do things the way you've been doing them no matter how well you're doing them, you're going to be obsolete in not too many years."

The convictions Koch was gathering combined with his regard for scientific inquiry led him to institute, among the steps in his management program, a "challenge process" in which employees are expected to speak up if they think they've got a better idea or see a flaw in the way things are being done. In his companies, he said, at all levels of leadership, "If people aren't challenging you, you're not a good leader, and if you're an employee and you have a better idea or you see a flaw in what's being done, and you're not challenging, you're not doing your job."

Asked what advice he would give to business school students attending the session, he said, "Find out what your innate abilities are that will enable you to create the most value and then turn those into skills that others will value and then use them to help other people improve their lives."

The creation of value to help others is the central tenet of Koch's program, but it grows not out of altruism for its own sake, but out of self-interest. As he writes in his book: "Adam Smith put it best: 'By pursuing his own interest [an individual] frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it.' " Even when Koch speaks of creating value for others he stipulates that it is not out of self-sacrifice but out of the benefits that will accrue to him in the course of helping another.

He believes, however, that if enough companies acted out of the kind of self-interest that seeks to create value for others, it could result in a transformation of society.

Jesuit Fr. Robert Spitzer, a co-founder and now president of the Napa Institute, in his summation of Koch's talk, lauded the business titan's humility and agreed with Busch: "You're a closet Catholic."

Both Turkson and Koch received a standing ovation and each was given a plaque: Turkson received Napa's Thomas Aquinas award, given annually; Koch received the institute's first Virtue in the Marketplace award, which Busch said will now be given annually in Koch's honor. Each also received a bottle of wine from Busch's Trinitas Cellars, a boutique winery. The award to Koch was given "in recognition of exemplifying the virtue of work and promoting the dignity of the worker through word and deed by embodying the teachings of St. John Paul II's Laborum Exercens."

Napa's bigger ambitions

Busch, in his opening remarks and in his introduction of Koch, made it clear that his personal ambitions and those of the Napa Institute went well beyond sponsoring seminars and conferences. This is not only high-end Catholic engagement (tickets for the conference were $2,500, with a discount for priests and nuns), it is high stakes Catholicism. And Busch doesn't shy from sweeping assertions.

"The reason [Koch] is here today is because he's talking about returning to the founding principles, founders' principles. He feels that we've gone off track and so I've kind of nicknamed him the refounder of America."

—Timothy Busch

"We're in a very hostile environment, we know, as a faith, and unfortunately it all starts about 10 minutes from this building in the U.S. capital," he said at the outset. "We have a government that is very hostile to Catholic teaching, especially on social issues," he said, "and we can't allow that to change our lives or our lifestyle, and for that matter to change our whole nation, we've got to turn it back to the principles it was founded on, Christian principles." He cast Catholic University as "our perennial partner" in the cause.

In introducing Koch, whom he described as an inspiration, Busch said the "nearly $50 million" gift that he and Koch helped arrange had "reenergized the Catholic University of America. We made it great again. We are the Catholic University of America and we have educated half of the bishops in this country.

"We can be the teaching pulpit for the American church, but also the teaching pulpit for the Vatican and for the global church," he said, without distinguishing whether he was referring to the Napa Institute, the university or both. "We can be that. And we will be that going forward, especially on the issues and topics of business."

Going beyond the university and his institute, he declared that "the reason [Koch] is here today is because he's talking about returning to the founding principles, founders' principles. He feels that we've gone off track and so I've kind of nicknamed him the refounder of America.

"It's very unlikely that a republic would last more than 200 years … before it has to be reconstituted," said Busch. "Now, we're still here but we're at a tipping point. I think that his principles, well beyond his watch, will be guiding us to refound our country into the country that made us the greatest nation in the history of the world," he said, referring to Koch. "We're going to continue to be the greatest nation in the history of the world."

He said that Koch challenged the audience with his belief that "We must do good," by turning from "cronyism, high regulation, enslavement. We must do good for all mankind," Busch concluded, "Otherwise God's mercy will not rain on us. God's mercy will not rain on us."

[Tom Roberts is NCR editor-at-large. His email address is troberts@ncronline.org.]