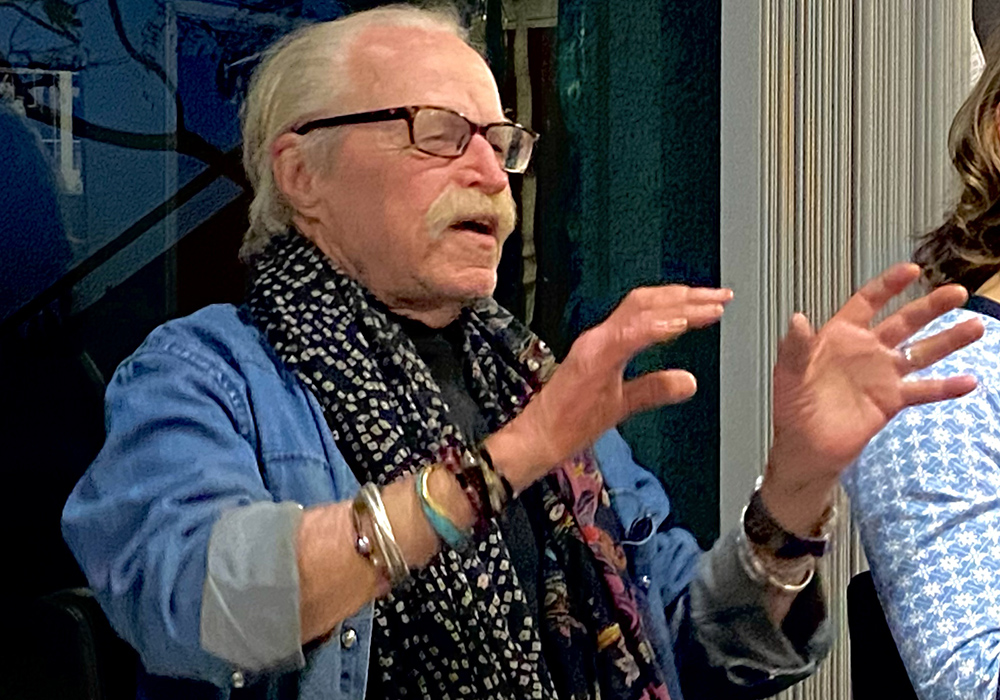

Jeff Dietrich, at center, speaks at a recent Loyola Marymount University reception to mark the release of the 40th-anniversary update of his 1983 book, Reluctant Resister. To the right is Charlotte Radler, a professor of theological studies at Loyola Marymount; to the left is Theresia de Vroom, a professor of English at Loyola Marymount. (Courtesy of Los Angeles Catholic Worker)

Jeff Dietrich has persisted on a soulful journey of more than 50 years of discerning journalism, social justice hospitality and sage civil disobedience at the Los Angeles Catholic Worker. That adds up to hundreds of thousands of adjectives/expletives, comforting scores of those afflicted, and a somewhat biblical count of 40 times being sent to prison.

Once an avid marathon runner, he admits today his body and mind tell him he is pretty much retired at age 77.

"But we call it active retirement," says Dietrich's longtime wife and coconspirator, Catherine Morris.

In the masthead of The Catholic Agitator, the L.A. Catholic Worker's bi-monthly newspaper, Dietrich is listed as editor emeritus and contributor; Morris is the publisher. The two also navigate their share of the household chores at the Los Angeles Catholic Worker's two-story sanctuary in the Boyle Heights area of East L.A., but it's getting more difficult.

Catherine Morris and Jeff Dietrich, spouses and "coconspirators" at the Los Angeles Catholic Worker (Courtesy of Los Angeles Catholic Worker)

Their communal residence has only five active worker members these days. It had as many as two dozen in the 1980s. The residual effects of COVID-19 continue a dependence on a core of dedicated volunteers in order to operate its L.A. Skid Row "Hippie Kitchen" three days a week with made-from-scratch hot meals and other services.

As Dietrich acknowledges, anarchists are harder to come by these days.

When some 50 guests arrived at a recent Loyola Marymount University reception to mark the release of the 40th-anniversary update of his 1983 book, Reluctant Resister (Marymount Institute Press, 250 pages), Dietrich was as much regaling as he was recruiting. Perhaps a student or two in the room might be inspired to keep the movement moving.

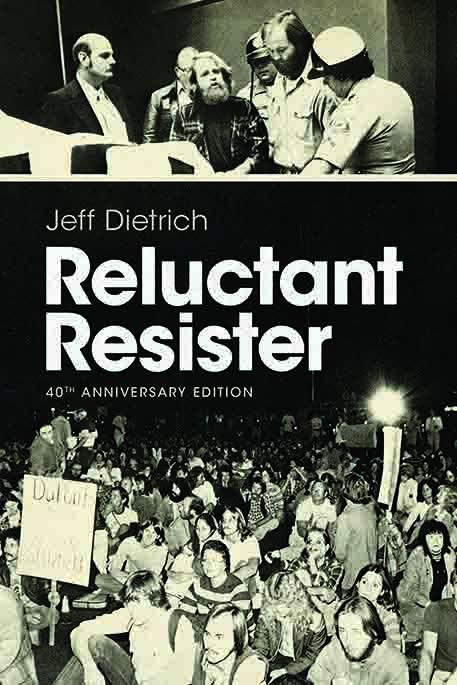

Cover of the 40th anniversary edition of Jeff Dietrich's book Reluctant Resister (Courtesy of the publisher)

Reluctant Resister is something of an epistolary novel focused on letters Dietrich wrote to Morris in late 1979 from a controversial prison sentence. Dietrich and Kent Hoffman were handed six months of jail time for disrupting a U.S. military technology show at the Anaheim Convention Center. The worker folks still refer to the whole event as "The Arms Bazaar."

Dietrich called it "a Gandhian-kind of campaign" to gather petition signatures, blockade the doors and participate in a candlelight demonstration. The judge's punishment brought more attention to Dietrich and Hoffman through curious media coverage. As a result, local residents pushed back, the trade show moved to Germany the next year, and it was again met by a Catholic Worker protest.

Dietrich has authored two previous books for this publisher: Broken and Shared: Food, Dignity, and the Poor on Los Angeles' Skid Row is a 2011 collection of essays originally published in The Catholic Agitator; in 2014, he wrote The Good Samaritan: Stories from the Los Angeles Catholic Worker on Skid Row.

It has become a trilogy of transformational outrage and outreach, revealing Dietrich's radical example of what faith-based compassion and empathy can look like. He explained further in a recent NCR interview, which has been lightly edited for length and context.

NCR: How do you get your head around the way this book from 40 years ago can resonate today while also documenting your soul-searching journey of nonviolent protest from the '70s?

Dietrich: I still think, in reading over these letters from prison, resistance is still the most important element of the Catholic Worker. Christians should still be resisters and should be a sign that the culture continues to go the wrong way. We should be a sign of life.

Jeff Dietrich, a member of the LA Catholic Worker community, speaks at a recent Loyola Marymount University reception to mark the release of the 40th-anniversary update of his 1983 book, Reluctant Resister. (Tom Hoffarth)

You admit that the fear and anxiety you had in serving prison time wasn't what you considered very heroic or virtuous. In the subsequent times you went to prison for protests, did it ever get easier?

No (laughing). The last time I went, I was still terrified I'd go to the eighth floor where all the tough guys were [at the Metropolitan Detention Center in downtown L.A., a U.S. federal prison]. It is never easy. If you're a Christian, you have to screw yourself up and pick up your cross. Jesus asked us to go out to the margins. Whatever way we can, we have to make people aware about how those on the margins are suffering — in jail, on Skid Row, in refugee camps throughout the world.

The single act of getting arrested doesn't seem to have a solid track record in changing laws. It is more of a personal sacrifice that brings attention to an issue. Are civil disobedience protests today — sit-ins, marches, any other forms — still effective? Should others follow your example?

I think of myself as a professional do-gooder. I'm a lifetime Catholic Worker and I don't expect anyone else to do what I do. I don't expect people to get up in the morning and go to Skid Row. I don't expect them to get arrested. But I expect them to live up to their obligation to have empathy for the poor, to elect people to government offices who do the right thing.

Advertisement

On the last Good Friday, the Catholic Worker did a Stations of the Cross in downtown L.A. with the Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice (or CLUE) and supported hospitality workers whose union contract is coming up. It juxtaposed the suffering of Christ with the economic hardships minimum-wage family providers have today in L.A. It got media attention. What did you come away with from being there that day?

It was a powerful witness. I was moved by the testimony of the workers at the stations we stopped. It brought a lot of people to experience the injustices the workers face. Just as the year before, a Stations of the Cross at San Gabriel Mission brought attention to the shameful way we have treated Indigenous people, which is just a scourge on our history. We pride ourselves for many years doing a Stations of the Cross around Skid Row, the police station, City Hall, and the downtown prison.

Jeff Dietrich, a member of the LA Catholic Worker community, signs a 40th anniversary edition of his book Reluctant Resister during an event at Loyola Marymount University. (Courtesy of Los Angeles Catholic Worker)

You've said that your belief in the Resurrection is what keeps you connected to the Catholic Church. What else keeps your faith alive?

I believe in the Gospels. I believe in Dorothy Day. I'm grateful for having found the Catholic Worker.

In some ways I feel my life started when I refused induction into the military in 1970. I went to Europe, came back with $5 in my pocket and thought I would be arrested for evading the draft. I spent that night in Kennedy Airport in New York, stuck my thumb out, found myself in St. Louis, and a hippie van pulled up and someone asked if I'd like to go to a peacemaker's conference. I thought: I'm a peacemaker.

That's when I met the Catholic Worker, because their group in Milwaukee was on trial for burning draft files. They ran a soup kitchen and clothing room, and I thought: This is what Jesus Christ would do if he was alive today — feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, sheltering the homeless and burning draft files. It was all being done by Catholics, occasionally by Catholic priests. I grew up Catholic but never heard about Dorothy Day or Daniel Berrigan.

I got back to California and my brother was in jail, in county lockup. When I was outside the jail after visiting him, I saw an old, blue, beat-up laundry van and it said in very tiny print on the side: "House of Hospitality." If I hadn't resisted the draft, hadn't gone to Europe, hadn't come back and hitchhiked, hadn't gone to that peacemakers' conference and then and hadn't gone all the way back across the country, I would never have known that House of Hospitality was the Catholic Worker. I just would have walked past the guy giving out coffee and doughnuts to people being released from prison, giving them clothes and bus tickets.

I think I only made two major decisions in my life. One was to refuse induction into the military and the other was to marry my wife, who kept me out of a lot of trouble. I just thought: What if you marry someone who wanted to do what you wanted to do, but did it better than you? That's how I married Catherine Morris. We do everything together. She keeps me focused.

The pope's prayer intention for April is for the spread of peace and nonviolence by decreasing the use of weapons by states and citizens. This again seems like it could be said at any time over the last century. How have you embraced Pope Francis' leadership of the church over the last 10 years?

I am so grateful Pope Francis is still alive (laughing). God bless him for synodality. In the time since Francis has been the pope, the church has been in reaction against Vatican II. Right now, I'm working on an essay about the late Seattle Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen, who I think came before his time and can be an example today.

Social justice work can burn people out if there isn't a faith-based foundation behind it. Do you ever feel burned out or does the Catholic Worker keep your fire burning?

Part of why people burn out is going to meetings. I don't have staff or editorial meetings. I'm grateful I can just do the work. I'm grateful to be able to live at the Catholic Worker. Grateful to live among our guests and grateful for the life Catherine and I have lived. I hope that I can die at the Catholic Worker. I hope it never closes before I die. I would love my last breath to be there.