Parishioner Bob Purgert looks at one of the damaged pedestals of the dismantled altar at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Cleveland. (Dennis Sadowski)

Shaking his head, Bob Purgert tilted one of the pedestals that supported the top of what is now a dismantled altar, stored in an unheated hall on the property of his beloved St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Cleveland's economically struggling Buckeye neighborhood.

He showed a visitor the casters under the pedestal that allowed for the altar to be rolled aside for special events. Chipped and splintered wood could be seen atop and along the sides of the pedestal, a second one next to it and the altar top resting on a table nearby.

"They didn't have to do this," a disappointed Purgert, 71, said of the damaged altar. Parishioners are deeply proud of the altar, which parish priest Fr. Julius Zahorszky built in 1966 to accommodate the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

Hungarian Cardinal József Mindszenty celebrated Mass at the altar during a 1974 visit to the parish. Pope Francis declared the cardinal, who resisted Hungary's communist government after World War II, venerable in 2019, making the altar a second-class relic if he is canonized a saint.

"They didn't have to do this," Purgert repeated. "They could have moved the altar. They could have moved it to the vestibule if they didn't want to see it, and then it could be moved back for weddings or funerals for our parishioners."

Purgert's ire is focused on the Chicago-based Institute of Christ the King Sovereign Priest, which since July has been establishing its presence at St. Elizabeth for Latin Mass adherents. The group celebrated its first Latin Mass at the shrine on Sept. 24.

Advertisement

Established by French priests in 1990 in Gabon, the institute is a group of priests devoted to promoting the Latin Mass as it was said before the council's reforms. In the United States, it is present at 23 locations in 13 states.

Parishioners, some with roots extending to the 1892 establishment of St. Elizabeth as the first parish in the Western Hemisphere for the Hungarian diaspora, are becoming increasingly concerned that the institute is sidelining their heritage and any connection with the novus ordo.

"They were supposed to leave the place alone, ask permission if they wanted to do anything in regards to revamping the church, changing things, moving things, giving things away, throwing things out," parishioner Mark Yonke, 57, said. He noted that the church is on the National Register of Historic Places and is recognized by the Cleveland Landmarks Commission.

Parishioner Mary Spisak, 90, who lived near the parish for years and now lives with her son in suburban Macedonia, Ohio, was among those incensed by the institute's actions. She wrote a letter to the diocese asking for an explanation.

"I'm very discouraged and disgusted at what these people are doing," Spisak said.

St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Cleveland (Dennis Sadowski)

Parishioner Lajos Karácsony, 60, who arrived from Hungary in 1995 and became a U.S. citizen in 2002, said he was "both concerned, upset" by the actions taken by the institute without consultation.

He recalled a meeting last summer among parishioners and Fr. Matthew Talarico, the institute's provincial superior from Chicago, who "presented a very nice program" on the group's plans for the shrine. "We agreed on everything," he said.

Now, Karácsony is not so sure, saying, "I'm wondering what these guys are doing."

It's not just the dismantling of the altar that has upset long-standing parishioners. In addition to Spisak, at least four other St. Elizabeth members have written to the diocese seeking an explanation about steps such as moving statues and banners that are symbols of Hungarian heritage; covering a carving of the Last Supper on the main altar; relocating the baptismal font from the sanctuary to a side vestibule; and moving English and Hungarian language sacramentary prayer books and contemporary priest vestments to secluded areas.

The changes, they said, were undertaken without notification as they understand was part of the agreement with the diocese that allowed the institute to locate at St. Elizabeth and for the parish to merge with another Hungarian Catholic community across town.

"What I don't think people understand is this is the mother church of Hungarians when we came to America. ... This is where it started. So, this has become like Plymouth Rock," said Purgert, whose grandmother graduated from eighth grade in the parish school in 1914, followed by his mother in 1944.

Bishop's 'instruction'

Cleveland Bishop Edward Malesic formally welcomed the institute to the diocese in an "instruction" issued July 28, 2023. At the time, he also announced that the former St. Elizabeth of Hungary Parish on the city's East Side would merge with another Hungarian parish, St. Emeric, on the Cleveland's near West Side.

The merger, he said, became necessary as Mass attendance at St. Elizabeth had declined for years.

St. Elizabeth Church, Malesic decided, would become a shrine where the institute's priests could celebrate the Latin Mass for Catholics who desired a place to worship under the old rite.

Malesic's announcement specified that the shrine would continue to promote "the Christian heritage of the Hungarian people as well as for divine worship according to the liturgical books in use prior to the reform of 1970."

Yonke, 57, whose grandparents appear in photos of parish organizations from 1904 in a museum in the church basement, said opposition to the institute's actions is not rooted in having the Latin Mass in the church. Rather, he explained, it is how the institute, under rector Fr. James Hoogerwerf — who uses the title "canon," as the institute designates its priest leaders — is going about remaking the church and the rectory with no communication with parishioners or Fr. Richard Bona, pastor of the merged parish.

For example, the institute in March began renovating the rectory. During a recent visit to allow researchers from Cleveland State University to review parish archives housed in the rectory, Yonke found the locks to the building had been changed.

"It was embarrassing," Yonke said of having to send the researchers away.

Altar dismantling

As closely as parishioners can determine, the altar was dismantled in late January. Rodney Johnson, a security guard who works for the church and the neighboring Miceli Dairy Products Co., said the process took at least a couple of hours.

During a morning round, Johnson recalled entering the church to see a worker, who described himself as a carpenter, working to take apart the altar. Fr. Jeffery Weaver, a diocesan priest who celebrates the Latin Mass on weekdays at the shrine, was standing nearby, Johnson said.

Questioning the work being done, Johnson said he told both men that longtime parishioners would be upset. Weaver responded, Johnson said, that "it was just a table."

Johnson left but returned, he estimated, about two hours later to see both pedestals separated from the altar top. "My stomach just dropped. I said to myself, 'I don't believe it,' " Johnson told NCR.

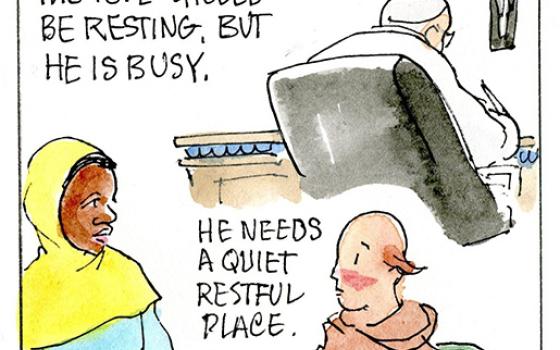

Pry marks and damage are seen on the dismantled altar at St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Cleveland. (Dennis Sadowski)

Johnson later described to Purgert and Yonke what he witnessed, sending a wave of anger and disappointment through the Hungarian community.

Nancy Fishburn, diocesan executive director of communications, responded to a request for comment sent to Fr. Donald Oleksiak, vicar general and moderator of the curia for the diocese. She offered few words on the altar being dismantled and the concerns raised by parishioners.

"Conversations are being held at the leadership level and parishioners will be communicated with directly on this matter," Fishburn wrote. "We do not believe this is a news story, but rather an internal discussion with members of St. Elizabeth."

Pressed for an additional response, Fishburn explained in a follow-up email that "the diocese is aware of some of the concerns being expressed and is working to address them directly with those involved."

She declined to address the role of Weaver as the altar was being dismantled and his work at the shrine, as well as the vetting process before the institute was permitted to locate at St. Elizabeth. Weaver did not respond to an email request for an interview sent through the diocese.

Hoogerwerf and Talarico did not respond to multiple emails and telephone calls.

Despite its terse reply, the diocese apparently is taking the situation seriously. In a mid-February letter to Spisak, Oleksiak said he had shared parishioner concerns with Bona and institute representatives days earlier. "During our meeting, it was discovered that the altar incident was an accident and will be repaired and replaced in the very near future. They regret the incident," Oleksiak wrote.

Bona did not respond to a call for comment.

The institute faced similar questions in 2019 after being invited to join St. Joseph Parish in Hammond, Indiana, by the Gary Diocese. Parishioners there quickly saw how the institute made little effort to incorporate itself into the existing parish community. After parishioners raised concerns, the institute relocated to St. Joseph Oratory in Merrillville, Indiana, within months.

Spisak and other parishioners remain skeptical that the pattern of actions by the institute will change despite their protests.

"With any inkling if we had known what was going to go on," Purgert said, "we would have never agreed to this [arrangement]."