A group of women gather outside Area 1 IDP Camp for internally displaced persons in Abuja, Nigeria. (Chinedu Asadu)

As the Nigerian capital of Abuja crawled out of sleep on a recent morning, Aisha Hassan quickly prepared food for her family of five before taking her 3-year-old daughter to a makeshift structure serving as the clinic for the internally displaced persons camp where they have been living for two years.

Originally from Gombe in northeast Nigeria where the Boko Haram terrorist group has operated for a decade, Hassan, like tens of thousands of others, was forced to relocate to Abuja in 2018, with the few belongings she could get hold of.

Hassan's daughter has malaria. At the camp, which currently houses about 2,000 individuals, food has been very difficult to come by, much less anti-malarial drugs.

Grace Maikani, a nurse at Area 1 IDP Camp in Abuja, Nigeria, takes notes while on duty. (Chinedu Asadu)

Hassan recalled to NCR how she was told by the nurse at the clinic that there were no drugs available, forcing her to run off in search of where she could borrow 150 naira ($0.39) to buy common malaria drugs, including Tylenol.

Unfortunately, the experience of her child was similar to that of most of the 53 million people — 25% of the population — who have malaria annually, according to data made available to NCR from the National Malaria Elimination Program, the federal government agency coordinating malaria response in Nigeria.

This means Nigeria carries the largest malaria burden globally. The country accounts for 27% of malaria cases and 23% of malaria deaths across the world, according to the World Malaria Report 2020, released by the World Health Organization Nov. 30.

The situation has been made worse during the coronavirus pandemic, as Nigeria's underfunded health care system has struggled to address both crises. In April, WHO warned that the number of deaths caused by malaria across the African continent could double during the pandemic.

At the center of the fight against Nigeria's malaria burden is Catholic Relief Services, which has been leading efforts to ensure that people like Hassan's daughter are treated and that as many persons as possible are protected from infection.

CRS started its malaria program in Nigeria in 2015, then as a small project integrated into its emergency response to the humanitarian situation during the Boko Haram insurgency.

Now working with the help of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the Catholic agency told NCR it has delivered at least 50 million insecticide-treated bed nets to citizens who need them. It is also providing malaria diagnosis, treatment and seasonal malaria chemoprevention.

Advertisement

"It is a very comprehensive project, which also includes training of community health workers and volunteers on how to use the rapid diagnostic test to diagnose malaria so that when a child comes to get tested ... the result of that test is out in just 20 minutes," Suzanne Van Hulle, CRS's global malaria adviser, told NCR.

Although investments in malaria response are coordinated by the government, efforts of donors and organizations such as CRS have been instrumental in the progress made so far — including the reduction in the prevalence of malaria from 47% to 23% in the past decade — even though the country still has a long way to go.

The burden over the recent years has largely remained the same, with the country accounting for 25% of global cases in 2019 and 2018, according to WHO.

Experts say Nigeria has done a poor job tracking malaria cases. Another issue is the country's geographic location on Africa's western coast, where the climate and the different ecological zones are favorable to the malaria parasite and the mosquito.

Sonachi Ezeiru, Chief of Party, Global Fund Malaria at Catholic Relief Services' Nigeria program (Courtesy of CRS)

Dr. Ifeanyi Nsofor, director of policy advocacy at Nigeria Health Watch, said other factors that have made elimination of malaria difficult include poor environmental management, and self-medication leading to antimicrobial resistance.

Sonachi Ezeiru, an official in CRS' Nigeria program, said poverty also plays a major role in the burden of malaria.

"With 40% of Nigerians living below the poverty line, access to health care is reduced and living conditions are deplorable [and] transmission of malaria is easier in such living conditions," said Ezeiru.

Ezeiru also cited human behavior as another factor contributing to the high malaria burden, arguing that while there is high knowledge about malaria, "this knowledge needs to translate to appropriate health care seeking behavior and actions that would prevent malaria transmission in the population."

As the pandemic began to unfold in early 2020, the National Malaria Elimination Program developed plans to streamline its activities and communicate the dangers of both malaria and coronavirus to Nigerians.

While this helped the government to not entirely lose focus in the malaria response, the pandemic made it unable to achieve much of its set targets, said Dr. Audu Mohammed, the program's national coordinator.

Dr. Audu Mohammed, national coordinator of Nigeria's National Malaria Elimination Program (Provided photo)

At a recent briefing attended by NCR, Mohammed said the agency was able to deliver only 17 million insecticide-treated nets out of the 31.5 million it had planned to replace at the beginning of 2020.

Dr. Olugbenga Mokuolu, the agency's malaria technical director, said challenges faced in the response to malaria in 2020 included diversion of resources and attention, and disruption in supply chains as a result of government restrictions on movement to try to stop coronavirus spread.

Mokuolu said that in addition to people's refusal to get tested and seek care as a result of symptoms similar to those of COVID-19, the pandemic also resulted in the depletion of the health workforce, stigmatization of malaria patients, and neglect of patients in holding areas before transfer to isolation centers.

The U.N. Refugee Agency estimates that more than 2 million Nigerians are internally displaced, primarily due to the Boko Haram conflict.

Only a small proportion of these displaced persons are housed in established camps, which are mostly overcrowded and scattered across various parts of northern Nigeria, including in Abuja, where 10 such camps exist.

Experts have expressed concern that the risk of contracting malaria is much higher among displaced persons, due to the overpopulation and unavailability of even basic health care.

One of the settlements is the Area 1 IDP Camp where Hassan and about 2,000 others live. Occupants told NCR that they have not received drug supplies from the government for months.

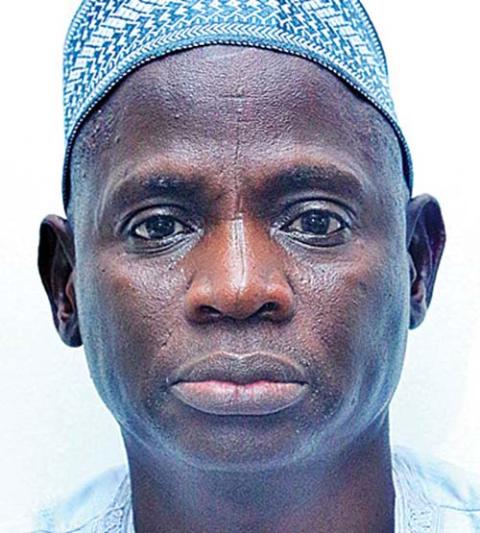

Aminu Abubakar, who lives in Abuja's Area 1 IDP Camp (Chinedu Asadu)

"For the past three months, nothing for this camp: no drugs, no food, nothing at all," Aminu Abubakar, one of the camp leaders, said during a recent visit.

"We don't even have medicine for malaria," said Abubakar, adding that when someone gets sick, people in the camp can only try to help the person afford Tylenol.

At the camp's temporary sickbay, Grace Maikani, the nurse in charge, confirmed that the only drug available is Tylenol. She added that she often has to give parents money from her own purse to help get drugs for their children.

Maikani said about 30 people in the camp report malaria symptoms on a daily basis.

While Ezeiru agrees that malaria burden and risk in the displaced persons camp is made worse by multiple infections and malnutrition, she said CRS has "worked closely" with the government's malaria program to provide bed nets and malaria testing to displaced persons.

Van Hulle said CRS's major focus in Nigeria is to reduce the number of deaths caused by malaria.

She said that while "it is going to take many more years" to eliminate the disease in the country, her organization is doing its best to see "that the country has all the resources to test and treat every single malaria case."

[Chinedu Asadu is a Nigerian journalist currently working as a staff writer with TheCable, the country's independent online newspaper.]