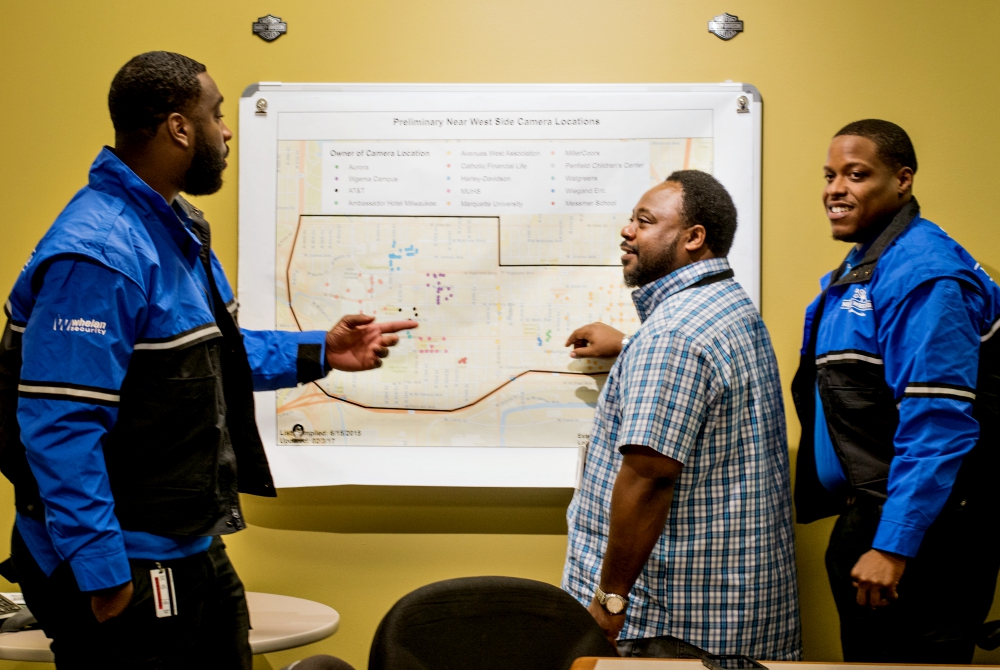

Community Prosecution Unit coordinator Bobby McQuay, center, and the Near West Side Partners ambassadors use geocoded data and resident input to address community identified issues on Milwaukee's Near West Side. (Courtesy of Near West Side Partners)

The 27th Street Tobacco and Wireless shop was not a good neighbor. Not to the children's center next door that provides early education for kids with developmental delays or disabilities. Not to Marquette University, less than a mile away. Not to the entire Near West Side of Milwaukee, a community already struggling with poverty, unemployment and crime.

In fact, the shop was a neighborhood nuisance, the reason for more than 400 calls to police over two and half years, for everything from drug dealing and illegal gun sales to aggravated assault. Yet, a loophole in Wisconsin law made it nearly impossible to revoke the licenses of standalone tobacco shops like the one on 27th Street.

But thanks to collaborative lobbying by several major neighborhood stakeholders — including Marquette and MillerCoors, which had connections with tobacco lobbyists — the law was changed in 2016, and, after a court hearing, the 27th Street Tobacco shop closed. The Penfield Children's Center eventually purchased the property and converted it into much-needed parking.

That's just one of the successes of the Near West Side Partners, a community revitalization group dedicated to improving its neighborhood by addressing economic development, housing, neighborhood identity and safety issues.

And it's an example of how Marquette — through its innovative Center for Peacemaking — tries to live out its mission of service to the local community in an unusual public-private partnership of community engagement.

"We want to be looked at as a good neighbor and partner in the community," said Marquette President Michael Lovell, who in 2014 became the first layperson to lead the 137-year-old university.

"This aligns completely with both our Catholic and Jesuit values," he said. "Jesuit universities were founded to have graduates who could improve the communities they were located in. That's really what we're called to do."

For example, Marquette's first new dorm in 50 years — a $108 million twin tower with its own dining hall called The Commons — opened last fall to nearly 900 students. They live across the street from the Milwaukee Rescue Mission, the largest homeless shelter in the state of Wisconsin.

"It's a statement for us to say we want to be with those we serve and be side-by-side with our neighbors," Lovell said, explaining why he believes the dorm's location near the shelter is a "positive."

Some colleges and universities face contentious "town and gown" relationships with nearby communities, where often affluent neighbors complain about such negatives as partying or inadequate parking. For schools in poor urban areas, the solution to neighborhood conflict can be to "buy the problem" by acquiring real estate adjacent to the campus.

Marquette, under Lovell, is trying another tactic: working with small and large businesses and other nonprofits to improve the neighborhood for all who live and work there, while avoiding displacing current residents through gentrification. "Buying the problem only solves the problem for one side; it doesn't solve it for the other side," said Rana Altenburg, Marquette's vice president for public affairs and president of Near West Side Partners.

Advertisement

Instead, the 10-year-old Center for Peacemaking — which houses the peace studies program — has become a clearing-house for Marquette's involvement with the partnership and other community-based peacemaking projects.

Marquette is "leading the charge," said Keith Stanley, Near West Side Partners executive director, who attended grade school in the neighborhood and has worked in community development for more than a decade. He also has worked in Milwaukee's City Hall.

"I wish we had a Center for Peacemaking in every neighborhood," he said.

'A neighborhood of neighborhoods'

As part of his dream to open a Catholic college in the middle of the 19th century, the first bishop of Milwaukee, John Martin Henni, purchased a parcel of land atop a hill overlooking the then-village, which at that point didn't even have paved streets. Eventually the city's most prominent roadway — Grand (now Wisconsin) Avenue — would go right past the newly incorporated Marquette College.

Today, the 93-acre campus, which stretches 12 blocks east to west and five blocks north to south, still calls that neighborhood — formerly referred to as "University Hill" — home. The Gothic Church of the Gesu sits just south of Wisconsin Avenue, which bisects the campus. Lake Michigan is about a mile to the east, while Marquette University High School is about a mile west.

University Hill is now called "Avenues West," one of seven neighborhoods that have come together to brand themselves as the Near West Side, a "neighborhood of neighborhoods." Nearly 28,000 people — including 10,000 university students — make the Near West Side their home, but the area is even better known as a place where Milwaukeeans go to work.

Marquette University Center for Peacemaking students distributed resident surveys at a neighborhood movie night on the Wgema campus of the Potawatomi Business Development Corp. as part of the Promoting Assets Reducing Crime initiative. (Photo courtesy of Near West Side Partners)

Within its boundaries are five major employers, all of which have signed on as "anchor institutions" for the partnership group: Aurora Health Care, Harley-Davidson, MillerCoors, Potawatomi Business Development Corporation (a Native American tribal business that operates a casino, data center and other non-gaming holdings) and Marquette University.

In the city's earlier years, the neighborhood was home to wealthier beer barons and city officials. The former mansion, now museum, of the Pabst family is just a few blocks west of the university. Later the Near West Side attracted other northern European immigrant groups. Today it is about 70 percent African-American and 30 percent white; the ratio is close to 50-50 if Marquette students are included, according to Near West Side Partners.

The neighborhood should be thriving, given its nearness to downtown and access to transportation, said Alderman Robert Bauman, whose 4th District includes about two-thirds of the Near West Side. Instead, about 60 percent of residents live in poverty and the median household annual income is about $18,000, he said.

About one quarter of the state's entire homeless population lives in the neighborhood, according to Altenburg.

White flight of the 1960s and '70s, combined with Marquette's decision in 1967 to relocate its medical school west* to merge with what is now the Medical College of Wisconsin, hurt the Near West Side, causing other hospitals and their workers to leave, Bauman told NCR.

"That left this huge void, which we're still dealing with today," he said.

Still, the alderman praises Marquette as a "great partner," and the Near West Side Partners as a model that could be replicated by other universities in high poverty areas.

'I wish we had a Center for Peacemaking in every neighborhood.'

—Keith Stanley, Near West Side Partners executive director

Violence and safety

In the spring of 2014, top executives at Harley-Davidson were interviewing a marketing manager candidate when they heard the pops of gunshots just before a bullet shattered a window in the conference room. The three people dropped to the ground and had to "army crawl" to a nearby office to safety.

The bullet that hit the motorcycle manufacturer's headquarters, which hugs the western edge of the Near West Side, had actually been fired from outside the neighborhood's boundaries during a domestic dispute. No one was injured, but the ordeal served as a wake-up call to address violence in the community.

The five anchor institutions met, ponied up some money, and the Near West Side Partners was born in October 2014. Its first, and most ambitious, project is the $1.5 million Promoting Assets, Reducing Crime or PARC initiative, which is spearheaded by Marquette's Center for Peacemaking.

The center takes a collaborative approach, with a focus on root causes of violence. "Our biggest obstacle is the [negative] perception," said Patrick Kennelly, the center's director. A former Catholic Worker, he and his wife have lived in the Near West Side for 15 years.

The initiative has two intersecting goals: reducing crime but also promoting neighborhood assets, including educational institutions such as Milwaukee High School of the Arts and Milwaukee Academy of Science; museums and theaters; and racial diversity in an otherwise segregated city.

"It's based on the idea that you can't just make plans, you need to create new experiences to form new beliefs to transform the community," Kennelly said.

Max Bertellotti of Marquette University Center for Peacemaking completes a Good Neighbor Survey of a property on Milwaukee's Near West Side as part of the Promoting Assets Reducing Crime initiative. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette University Center for Peacemaking)

All projects — from pop-up galleries to business development to street beautification — are data-driven, thanks to the center's nearly 40 Marquette faculty members doing applied research on community peacemaking. Since the launch of the initiative in April 2015, overall crime in the Near West Side has decreased by 11 percent, Kennelly said.

Even the perception is changing. A resident survey shows that crime no longer tops their list of concerns, Stanley said. Marquette's Lovell said he no longer gets questions about the safety of the campus when talking with prospective students and their parents.

A recent Near West Side Partners "safety meeting" demonstrates the collaborative approach, with representatives from businesses, schools, landlords, residents and the two police departments that serve the area: Milwaukee's and Marquette's.

Topping the agenda is traffic safety, with a discussion about newly painted crosswalks and temporary curb extensions to address speeding and other issues. Another idea is for "traffic calming" signs that have the additional benefit of neighborhood branding.

This "broken window" approach that addresses smaller-scale issues of disorder to prevent more serious crimes seems to be working. Marquette Police Chief Edith Hudson sees not just lower crime statistics but a new attitude of "everyone coming together to make the entire area a better place."

The PARC initiative also helps fund a community prosecutor, whose office is located in the neighborhood to better facilitate relationships in the community. "This model is really the best way for effecting changes in a [offender's] trajectory, long-term, and the neighborhood's, as well," said Assistant District Attorney Catelin Ringersma, of the Near West Side Community Prosecution Unit.

The goal is a more peaceful neighborhood, Ringersma said. Working with the center and other partners, law enforcement can help "quell some of the angst and anger that goes on in neighborhoods," Hudson said, adding that she describes that as "peacemaking."

'This model is really the best way for effecting changes in a [offender's] trajectory, long-term, and the neighborhood's, as well.'

—Assistant District Attorney Catelin Ringersma, of the Near West Side Community Prosecution Unit

Positive peacemaking

The partnership group believes that "you can't just police your way to prosperity," said Near West Side Partners president Altenburg. "You can deal with blight, but if you don't replace it with something positive and productive, it's just going to come back."

The more comprehensive approach taken by Near West Side Partners ranges from hosting a "Trunk-or-Treat" event at Halloween to publishing a restaurant guide, working to bring grocery stores to a neighborhood previously seen as a "food desert," or obtaining grants from government and nonprofit groups.

Some 26 new businesses have been opened in the past two years, according to Stanley, including several small start-ups through the Rev-Up MKE, a "Shark Tank"-type business competition coordinated by the Center for Peacemaking.

But the Near West Side doesn't suffer from a lack of jobs, says Altenburg. With 16 schools and universities, large and small businesses, and 94 social service organizations, it is "a destination neighborhood," she said. "What we don't have is a more diverse residential population," Altenburg said.

To that end, Near West Side Partners' "Live-Play-Work" program offers subsidies to workers who want to rent or buy homes in the neighborhood, while the Good Neighbor designation identifies and builds community among landlords with a history of positive tenant relations.

The Marquette University Center for Peacemaking is an academic research center focused on exploring the power of nonviolence. (Photo courtesy of the Marquette University Center for Peacemaking)

In addition, the center and Near West Side Partners were recently awarded a $1.3 million Choice Neighborhood grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to revitalize a distressed public housing development. Marquette is the first university in the country to be awarded that grant.

The improvements are already noticeable, from the new Potawatomi data center on what used to be a vacant lot across from Concordia University's old campus to the upgrading of the historic Ambassador Hotel to a new high-end vodka distillery, says Milwaukee Journal Sentinel business reporter Tom Daykin, who has covered commercial development for 25 years.

He praises Marquette's "significant investments," including the residence hall and a sports research complex. Recent improvements seem to mirror the university's $50 million "Campus Circle Project" of the 1990s, which was designed to address negative perceptions of the neighborhood in the wake of the arrest of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, who lived about a mile away.

But the university's idea in the '90s to close a portion of Wisconsin Avenue, to essentially wall off the campus, was viewed as arrogant and eventually dropped, Daykin said. "That did not go over well."

Bauman also wishes the partnership would focus more on housing — especially increasing homeownership in a neighborhood that is nearly 90 percent rentals — rather than commercial and retail development. The city also would have liked to have seen more money from the partnership, which has already funded the $2 million PARC initiative and raised more than $2 million of a $5 million goal for economic development.

While "it's not for me to tell private companies how to use their money," Bauman said his original budget for the proposed partnership was $50 to $60 million.

"To undo 40 years of embedded poverty, you have to invest heavily," he said. "Small-scale development doesn't really change the fabric of a neighborhood."

Urban renewal requires significant capital and some risks, Bauman said. "The rate of return may be very slow and be measured in non-monetary ways, like the well-being of citizens. That is certainly a return on investment, just not one you can put in a bank."

But the Center for Peacemaking's founder, Terrence Rynne, knows nonviolent direct action can have significant results.

"It's been used against injustices — to get civil rights, economic rights, to change systems," said Rynne, a retired health care marketer and hospital administrator (and member of NCR's board).

The center's mission encompasses not only violence prevention or conflict resolution, but the broader vision of building of structures and relationships in communities so all can thrive, said Kennelly.

"We're trying to help people to embrace nonviolence," he said, "because by saying there is a nonviolent solution, you're really saying that there is some sort of hope for transformation."

[Heidi Schlumpf is NCR national correspondent. Her email address is hschlumpf@ncronline.org. Follow her on Twitter @HeidiSchlumpf.]

*This story has been updated to correct that Marquette decided to relocate its medical school west.