Benedictine St. Mary Lou Kownacki in 2018 (Courtesy of Benedictine Sisters of Erie)

Benedictine Sr. Mary Lou Kownacki, a major force behind the ministries and outreach that shaped the Erie Benedictines in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, died Jan. 6 at Mount St. Benedict Monastery in Erie, Pennsylvania, after three years with uveal cancer. She was 81.*

A native of Erie, Kownacki entered the Benedictine community in 1959 when she was 17 and made her final profession in 1965. A poet and peace activist, she was also the behind-the-scenes inspiration for some of Benedictine Sr. Joan Chittister's major works.

The Erie Benedictines, a small community in one of Pennsylvania's faded industrial centers on the northern edge of the country, has often played an outsized role in the Catholic community in the United States and beyond. The well-known public face of the community is Chittister, who has written extensively on spirituality, women's rights and religious life. Now in her mid-80s, Chittister continues to produce books and columns while maintaining a demanding speaking schedule nationally and internationally.

Not as widely known is the significant collaborative role that Kownacki maintained for decades. She was a founder of ministries within the community. They included Benetvision, which distributes regular newsletters and other communication based on Chittister's writing, and Monasteries of the Heart, an online community of more than 24,000 members worldwide who explore Benedictine spirituality.

Kownacki "was the living integration of the active and the contemplative soul," Chittister said in a statement reflecting on her friend's life. "Her spiritual depth knew no end; her heart's outreach, no limit. Her favorite quotation was from Ryokan, the Zen monk who wrote, 'Oh that my monk's robe were wide enough to embrace the whole world.'

"It was out of all of that," said Chittister, "that she became my muse."

Ryokan was a 19th-century monk and poet. Kownacki composed a book of poems, Between Two Souls: Conversations With Ryokan, in which she responds to Ryokan. In it she writes of her own vocation:

Thinking back I recall my novice year:

Dusting long hallways of venetian blinds

I repeated holy phrases

Desiring to become a bow of praise

Praying with outstretched arms each day

That my arms, like the Spirit's wings,

Might grow wide enough to embrace

The suffering of the world

That desire understandably fell short of reality, but the embrace was enormous and found expression in many forms as Kownacki and others initiated ministries that transformed large swaths of Erie life. The ministries were in response to a major change in direction for the Erie Benedictine community.

For decades, the Erie Benedictines had taught generations of girls and young women from Erie's lower economic strata. But it became clear in the years following Vatican II, and as vocations to the religious life diminished in the aftermath of World War II, that the community's St. Benedict Academy was unsustainable. A combination of a 15-year renewal process and economic realities brought the community to an inevitable point. During Chittister's 12-year tenure as prioress, the community voted to close the academy.

What replaced its long identity as a teaching community was a new way of viewing the purpose of religious life called a "corporate commitment." It was a step designed, said Chittister, to answer the question: "Where was our unity without the common ministry of teaching?"

Advertisement

By a one-vote margin in 1978, according to a publication celebrating the community's 125th jubilee, the community decided that its corporate commitment would be peacemaking. While the commitment could be approached in broad terms, including work in education, housing, health care and other individual ministries, Kownacki was especially well placed to exemplify the core of the new direction.

On Kownacki's 60th anniversary as a member of the Erie Benedictines, a community statement described her progression "from the teaching ministry she undertook as a young sister to the peace and justice work that has filled the majority of her life."

She was a founding member of Pax Center, an intentional living community "that brought together sisters, activists and people in need." She served as national coordinator of Pax Christi USA and head of Benedictines for Peace, efforts aimed at challenging church and civic leaders to find nonviolent solutions to local and global conflicts. She also was executive director of the Alliance for International Monasticism, which promotes solidarity among monastics around the world.

She served as director of development and communications for the Erie community from 1992 until 2002 and director of Benetvision Publishing from 1992 until 2022. She was founder and executive director of the Inner-City Neighborhood Art House from 1995 to 2005. The Art House, where she also served as writer-in-residence and poetry teacher, provides free art and music lessons to poor children. She was also one of three "founding mothers" of Emmaus Soup Kitchen in Erie.

Benedictine Sr. Mary Lou Kownacki with children from the Inner-City Neighborhood Art House in an undated photo (Courtesy of Benedictine Sisters of Erie)

Over the decades, she wrote and published 10 books, including several volumes of poetry, and she co-edited two other volumes.

Her first book, Peace Is Our Calling: Contemporary Monasticism and the Peace Movement, was published just three years after the vote on the corporate commitment.

It is a first-person account of both her involvement in peacemaking in Erie and a travelogue of exploration in the United States and overseas that included meetings and interviews with noteworthy clerics, religious and laypeople exploring possible connections between peace activism and monasticism.

Underpinning her exploration, however, are viewpoints about religious life and church in general that more than 40 years later might appear especially prescient.

It was only in the wake of the 1962-65 reform council, Vatican II, that women religious were free to pursue such explorations. She wrote: "The people who took the Spirit at its word and went after renewal with a vengeance were women religious. The reason for this becomes clearer as the years pass — women had the most to gain from renewal, the least to lose."

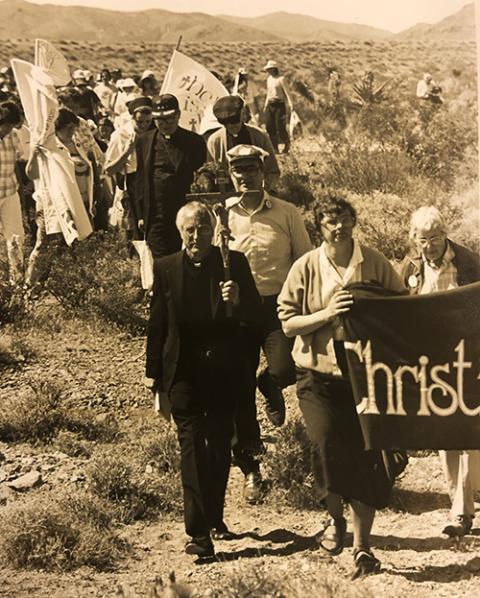

Benedictine St. Mary Lou Kownacki, second from right, is seen during a May 5, 1987, Pax Christi USA witness at the Nevada nuclear testing site northwest of Las Vegas. To the left Kownacki is retired Detroit Auxiliary Bishop Thomas Gumbleton. (Courtesy of Benedictine Sisters of Erie/Pax Christi USA)

Women religious, while overseen by the clerical culture, are in important ways disconnected from it, a point she makes in the book.

"We were trying to throw off yokes of oppression placed on our backs by Church law, by historical circumstances, by cultural expectation and by ourselves. Some of us tasted freedom and can never settle for anything less than the promised land, no matter what the price; others tasted freedom and are returning in part or en masse to the security of Egypt."

Chittister's characterization of Kownacki as muse is more than a figurative appellation. If the Erie Benedictines, largely through Chittister's writing and speaking, became known as a place that entertained big questions, it is clear through her own writing that Kownacki was not shy about expressing the same questions — about the future of religious life, parish structure, the nature of faith and ideas about God. Nor was she at all reluctant to push her better-known friend to take on such matters at book length.

"Her hand has always been at my back, pushing me where I wouldn't have gone," Chittister said in a recent interview. Repeatedly, she said, and often in the context of having lunch, Kownacki would raise a topic and eventually convince Chittister to do a book. So much of her published work, Chittister said, began with the two of them having lunch and Kownacki pressing her with questions.

One of the most recent examples had its roots in a lunch conversation some 25 years ago when Kownacki first raised the possibility of Chittister writing a book on monasticism for ordinary people. Listing terms that professed monastics use, Kownacki urged Chittister to unpack the language for the wider population.

"I groaned," recalled Chittister. "I'm not going to spend my time writing a monastic glossary."

To mollify her friend, Chittister agreed to write down a list of terms that might be worth unpacking. They were written on a sheet of paper — lauds, vespers, vows, stability, and so on — which she slipped into her notebook.

Benedictine Sr. Joan Chittister, left, and Benedictine Sr. Mary Lou Kownacki in July 2014 at the release of the book Joan Chittister: Essential Writings (Orbis), which Kownacki co-edited (Courtesy of Benedictine Sisters of Erie)

Sometime last year, the two went out to lunch again, and Kownacki asked, "What did you do with the words — that list of monastic words? You haven't started that book, have you? I think you should start that now."

Chittister couldn't believe she remembered the list, but she relented and wrote a book titled The Monastic Heart: 50 Simple Practices for a Contemplative and Fulfilling Life. Chittister was certain no one would want to publish it. Random House did, and it was released in September 2021.

The topics Kownacki raised over the years were not spur of the moment or random. In an interview conducted by Benedictine Sr. Linda Romey, a member of the Erie community, about the book Peace Is Our Calling, Kownacki spoke of someone's observation that a monastery stands as "a question mark to society."

"I would add," she said, "that the monastery should always stand as a question mark to the institutional church. It's very Jesus-like. Jesus resisted both temple and king by acting differently than the status quo — welcoming outcasts, identifying with the poor, treating women as equals, refusing an 'eye for an eye,' empowering the disenfranchised, speaking truth to power. ... The monastery does likewise because we believe that Jesus saw with the eyes of God and so we imitate."

Services will take place at Mount Saint Benedict Monastery: Visitation 2-5 p.m. January 9; Service of Memories at 7 p.m. January 10; Visitation 2-5 p.m. followed by a Liturgical Celebration of the of Life of Sister Mary Lou at 5:30 p.m.

*This story has been updated to correct Kownacki's age when she died and other dates. In addition, funeral services information have been added.