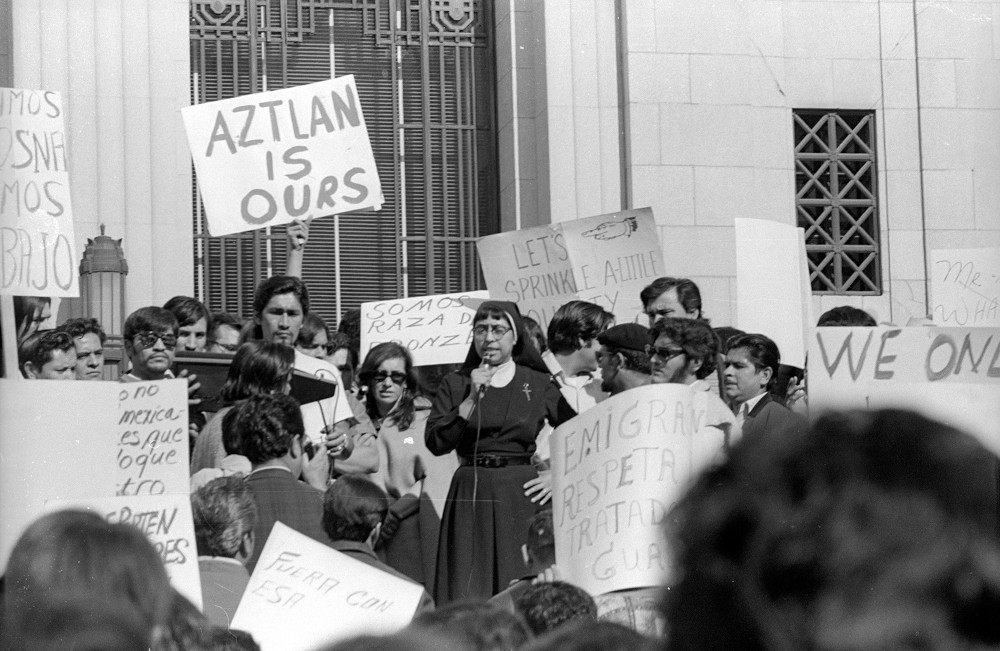

A nun speaks to protesters in front of the California State Building in downtown Los Angeles at an immigration march against the Dixon-Arnett Act on Jan. 22, 1972. (AP/RNS/Pedro Arias/La Raza Photograph Collection/Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.)

The UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center archives Mexican American life before, during and after the Chicano Movement.

These collections give insight to Mexican American leaders in the 1940s and '50s and those who participated in the civil rights movement that advocated for voting and political rights in the '60s. It also tracks what became of these activists, who pursued careers in government, law and the entertainment industry.

But religion is an aspect of life that has not been prominently highlighted in this collection.

That is now changing.

Through a $349,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the center has launched a three-year project to preserve its collections reflecting the role of faith, spirituality and religion in Mexican American culture.

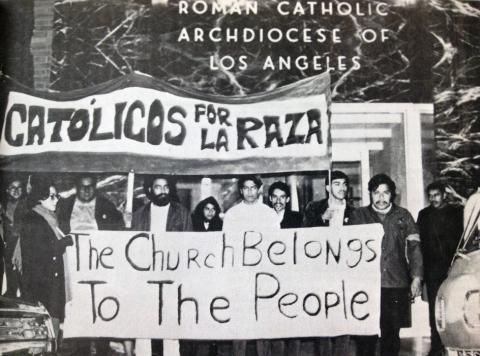

The collections highlight churches and faith-based organizations such as Church of the Epiphany, an Episcopal congregation where activists planned the Chicano Moratorium to protest the Vietnam War draft; Homeboy Industries, a gang-intervention and rehabilitation organization founded by Jesuit priest Gregory Boyle; and Católicos por La Raza, a Catholic lay group that criticized the church's neglect of the poor and the lack of Mexican American representation within the institution.

It includes figures like the Rev. Richard Estrada, who has advocated for immigrants and LGBTQ people; Sr. Karen Boccalero, a Franciscan nun who started a community arts center in East Los Angeles; and others whose lives reflect faith-based values, such as Mexican American civil rights activist Lupe Anguiano, who challenged policies of the Catholic Church while she was a nun.

Católicos por La Raza members demonstrate in Los Angeles. (AAP/RNS/Photo courtesy of UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center)

With more than 90% of U.S. Latinos identifying with a religion or faith, Chon Noriega — director of the Chicano Studies Research Center — said there is a "surprising absence"of humanities research related to the role of religion and spirituality in the community's history.

A common assumption is that Mexican Americans are all Catholic; while many Latinos do identify as such, Noriega said it's important to recognize the different faith backgrounds within the Mexican American community. Even Catholicism has different subsets, such as the Jesuit order of Catholic priests, Noriega said.

By acknowledging these nuances of religion, "you end up with a much more complex understanding of people," Noriega said.

With this funding, the center will hire an archival intern and students to help organize and describe documents and photos that give insight into religion and faith in Mexican-American social history. They will sort through legacy collections and recent acquisitions and digitally preserve materials consisting of nearly 250 linear feet of documents, 125 audio recordings and more than 14,000 photographs and slides.

The Chicano Studies Research Center is aiming for the collections to be used in dissertations, scholarly books, undergraduate and graduate research projects, teaching assignments that provide hands-on experience with archival research, and as loans for museum and library exhibitions. These archives will be available for the general public.

Robert Chao Romero, a professor of Chicana/o studies and Asian American studies at UCLA, said the project signals a "new day."

Christianity within the Chicano studies context is often shamed as the religion of the colonizers, said Chao Romero, who in his book " Brown Church, " explores the identity struggle over faith and heritage among Latinos.

While "there's a lot of truth to that," Chao Romero said, it's also important to highlight the role religion and faith played in Cesar Chavez's advocacy for farmworkers and the sanctuary movement in which churches took in immigrants fleeing violence in Central America.

Chao Romero said religion has served as a means toward advocacy and community organizing.

"Religion is a source of spiritual capital for the Latino community," he said.

Advertisement