Members of the Southern Baptist Convention and guests lift their hands in prayer during the SBC's annual meeting in Birmingham, Alabama, June 11. (RNS/Butch Dill)

Since they were first offered an opportunity to pool their resources and buy background checks on volunteers and employees at a discount 11 years ago, about a third of Southern Baptist churches have signed up for the OneSource program from LifeWay Christian Resources.

Earlier this year, LifeWay reported that 16,000 congregations and other church organizations ran background checks on men and women it hired through a service called backgroundchecks.com. (The Southern Baptist Convention has so far resisted calls to set up a database of its own, saying the national registry was more dependable.)

Other denominations are also increasingly using searchable databases on prospective employees as the #ChurchToo movement begins to shift church attitudes toward sexual abuse and prevention.

Most background checks sift through more than 600 million felony, misdemeanor and traffic records. Perhaps most importantly, they also check the nationwide sex offender registry.

But that may give churches and other religious groups a false sense of security about preventing abuse, experts say.

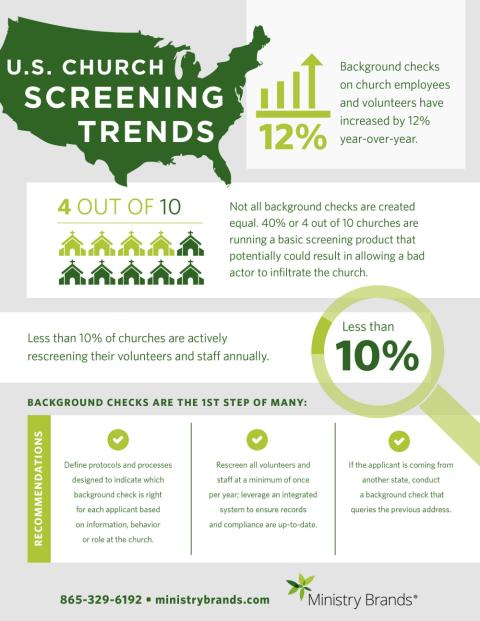

"We make it clear to folks you will have to do a more in-depth search," said Josh Weis, executive vice president of Ministry Brands, a provider of church management software that also sells screening products for some 30,000 congregations, mostly Protestant. "Not all background checks are created equal."

Federal law requires all 50 states to implement sex offender registries. But the law does not address lower-level sex abuse convictions, and state laws regarding sex abuse vary from state to state.

That means some sex offenders can slip through the cracks.

Jeffrey Epstein, the New York financier charged with sex trafficking underage girls, is a good example. Epstein was registered as a sex offender in Florida. But in New York, where he owns a residence, he was not required to show up for periodic check-ins required by law after he changed his address to the Virgin Islands, The New York Times reported.

And in New Mexico, where Epstein owned a 26,700-square-foot mansion south of Santa Fe, he was able to avoid inclusion in the state's registry altogether because his conviction involved a 17-year-old. That is the age of consent in New Mexico.

Churches need to invest in deeper background searches for employees and volunteers and not settle for less expensive searches in the state where the congregation is located, Weis and representatives of other background check companies insist.

Ministry Brands recently released an audit of the 29,768 churches that have used its "Protect My Ministry" brand, a product for churches. It showed that 40% of those church and ministry clients do not take advantage of deeper, more thorough searches of each of the 50 states.

The report also recommended that congregations require applicants to provide Social Security numbers for background checks so it can detect people using false names or aliases.

Just last week, the Sarasota County (Florida) Sheriff's Office charged Charles Andrews, a minister, with 500 felony counts of possession of child pornography. Andrews, who served Osprey Church of Christ in Osprey, Florida, is registered as a sex offender in Alabama.

Officials said Andrews used email addresses and a social media account that were not reported to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, the Orlando Sentinel reported. It was not clear if church members knew Andrews was a registered sex offender in Alabama. The church's telephone number was disconnected.

Elizabeth Jeglic, a professor of psychology John Jay College, City University of New York, who studies sex offender registries, said such cases are pretty rare. Only 5% of people on the sex offender registry are repeat offenders, according to a recent study in New York state. The vast majority are first-time sex offenders.

Running potential employees through the sex offender registry is useful, said Jeglic. But the data it provides is limited.

Advertisement

The national registry became law after a series of child rapes and murders, perhaps the most famous being that of Megan Kanka, a 7-year-old girl from New Jersey who was raped and murdered by her neighbor in 1994. Her murder led to a series of bills requiring a sex offender registry, with a database tracked by the state and community notification of registered sex offenders moving into a neighborhood. President Bill Clinton signed Megan's Law in 1996, making sexual offender registries required by all 50 states.

But in recent years, the effectiveness of the national sex offender registry has been called into question. For one thing, the database is not updated in real time. It can take months or years before the database is updated with people who have been released from prison on sexual offenses. For that reason, companies providing churches with database searches recommend that all employees be screened every year.

"Churches have this idea of one-and-done," said Weis. "We recommend they do it annually."

In addition, a 2010 South Carolina study showed that many sex offenders plead down their to charges to a nonsex crime so they aren't included in the registry.

That, plus the variability of state laws on sex abuse, leads researchers to conclude that screening people through databases such as the national sex offender registry or the state's criminal database won't guarantee a sex-abuse-free church environment.

"We're spending a lot of time and money on enforcing restricted policies that don't prevent recidivism instead of working on prevention," said Jeglic.

She recommended that congregations work on policies or procedures to reduce the incidence of sex abuse. That could mean, first and foremost, establishing clear training protocols that forbid church workers to be alone with a child, even in the bathroom, and submitting all new hires to a period in which they are shadowed.

"As a woman and as a mother, it feels nice to be able to look [someone] up and know," Jeglic said. "But as a researcher, the data doesn't help prevent any future sex crimes. A lot of the information on the registry is incorrect. It gives us a false sense of security."