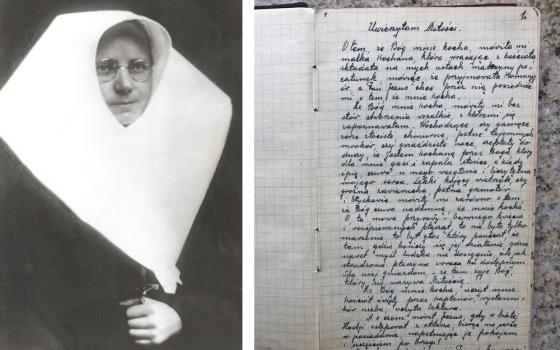

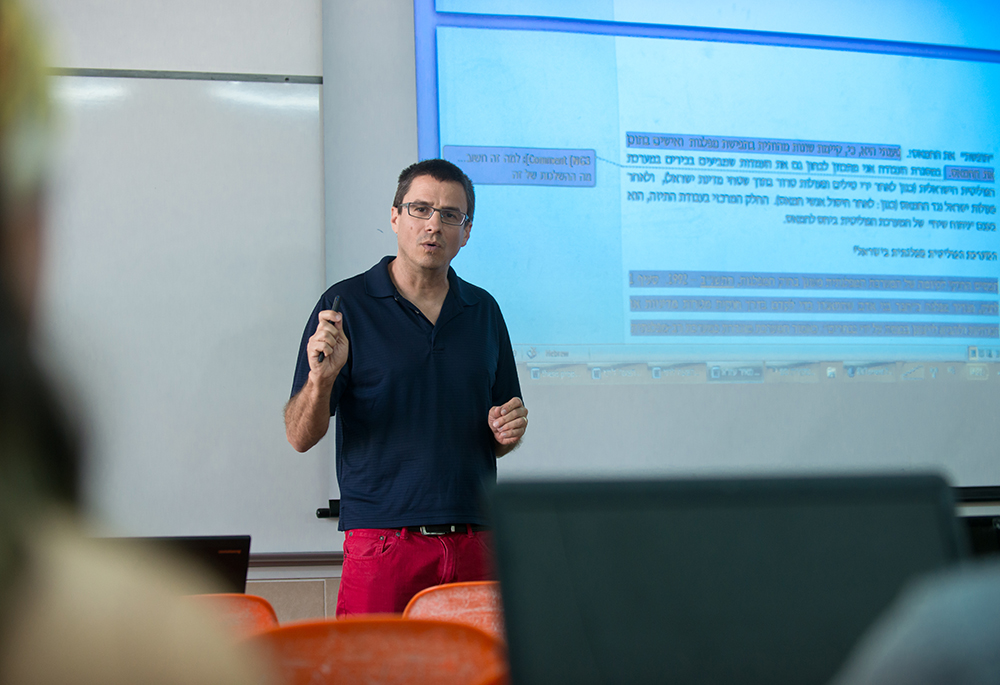

Neve Gordon, professor of human rights law at Queen Mary University of London, spoke to NCR about the experience that made his commitment to Palestinian self-determination irreversible, and made his critique of Israeli policy toward Palestinians unremittingly sharp. (Courtesy of Neve Gordon)

Neve Gordon knows precisely when he moved from being an activist-at-a-distance with sympathies for the Palestinian cause to being in a "relationship of solidarity" with Palestinians under siege.

It was an experience that made the commitment of this Jewish Israeli academic to Palestinian self-determination irreversible and his critique of Israeli policy toward — and violence against — Palestinians unremittingly sharp. That act of solidarity and all that flowed from it extracted a hefty price, a "self-imposed exile" in which he and his partner, Catherine Rottenberg, and their two sons, ended up in London.

From that distance, in a November column for Al Jazeera, he wrote of the current siege underway in Gaza. He took note of billboards throughout Israel bearing the legend, "Together we will win."

But what does winning mean? "For the religious right," he said, "the heinous Hamas massacre is considered an opportunity to resettle the Gaza Strip with Jewish settlers," he said.

"For the Israeli political right and many on the political center," he wrote, " 'winning' means transforming parts of northern Gaza and a large perimeter around the Strip's northern, eastern and southern borders into a no-man's land." In effect, it would result in "confining the Palestinians into an even smaller prison than the one they have lived in for the past 16 years."

Finally, he said, for the "remaining political center and many Jewish Israeli liberals," there is little understanding of what winning means "beyond the exertion of horrific violence to 'destroy Hamas.' "

For Neve Gordon, "winning" is an impossible end to the invasion of Gaza. The war is but the latest and grimmest evidence of a doomed strategy.

Palestinians gather March 4 at buildings in Rafah, in the southern Gaza Strip, that were destroyed by an Israeli airstrike amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas. (OSV News/Mohammed Salem)

Solidarity 'that creates a certain bond'

The period of personal transformation he speaks about occurred during the second intifada, a violent and bloody period that exploded on Sept. 28, 2000. On that day, the legendary military figure and soon-to-be prime minister, Ariel Sharon went, "accompanied by hundreds of Israeli police officers, to the holy site in Jerusalem known to Jews as the Temple Mount and to Muslims as the Noble Sanctuary."

Palestinians considered the visit a desecration of space sacred to Muslims and responded violently with riots that lasted, depending on the estimate, from four to five years.

Israel was accustomed to war, but the second intifada was different from previous military engagements. It was, according to The Jerusalem Post, "a defining event in Israel's history."

The conflict did not occur on battlefields or defined territories. Palestinians, instead, brought the violence into the city of Jerusalem, with bombings at restaurants, on buses and in business and entertainment districts. Fear prevailed, a companion to even the most ordinary activities.

It was also a defining event for Gordon, but in a different way. To that point, he had been a distinctive voice in the degree to which an Israeli Jew would advocate for the Palestinian cause. Much of that advocacy was contained in columns he wrote for NCR from 1996 to 2009. Today, a 58-year-old professor of human rights law at Queen Mary University of London, he said he had been in contact with Palestinians from his early 20s. He was involved in peace groups and nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs. At age 27, he became the first director of Physicians for Human Rights, Israel.

Israeli soldiers carry their equipment as they prepare to leave the Israeli settlement of Kfar Darom in the central Gaza Strip, Sept. 11, 2005. In 2005, in the wake of a second and far more violent intifada, or uprising against Israeli occupation, Israel withdrew its soldiers and over 8,000 settlers from Gaza. (AP photo/Pier Paolo Cito, File)

During the second intifada, he explained in recent interviews conducted by Zoom and email, "I joined and helped create a group in Jerusalem called Ta'Ayush ["living together"] that was a Jewish-Palestinian group that was not an NGO, it was a social movement."

It drew him into a deeper understanding of the other. "You hear their side, and you slowly — for me at least, slowly — began understanding … the depth of the problematics of the side that I belong to as a Jewish Israeli." In that understanding, he said, Israel's "policies became worse."

Gordon was no stranger to war. As a member of the Israeli Defense Force (a paratrooper), he was around 21 when he was critically wounded in his third and final year of compulsory service, shot while engaging in a campaign inside Lebanon. It was one of the events, among many, that increasingly convinced him of the need for nonviolent solutions.

The period of the second intifada for Gordon was not a time of just sitting around with Palestinians talking policy. "It was every week or every other week, we'd go to the West Bank and break the military siege, and work together with villages, being together on the ground when there's military violence against you, when you're under tear gas, when people are arrested. And there's this solidarity under these conditions, and that creates a certain bond. That, and a certain recognition of the kind of violence that they are subjected to, that is not abstract, but real and embodied in many ways."

An atheist with religious influencers

That defining moment in his relationship with Palestinians was the result of a mix of religious and secular influences that had brought him to both a moral and political conclusion: "to intervene for the underdog, to be with the weak."

Where did this conviction, resonant with religious tones, come from?

He granted, after noting that he is an atheist, that it was "a very good question." He is not antagonistic toward religion, and recalled that a couple, Anne Pettifer and Peter Walshe, both activists — he a revered and now-retired professor at Notre Dame — were big influences. They met while Gordon was doing graduate work, including a doctorate in politics, at Notre Dame. Pettifer and Walshe are, in Gordon's description, "devout Catholics." They were also the ones who suggested he write for NCR. "I remember Anne asking me, 'If you don't believe, where does your conception of justice come from?' Which is your question in a sense," he added.

"I mean, I grew up going every Saturday to a synagogue," Gordon said. He is "very much influenced by different readings, both of Judaism and Christianity." Even though there are elements of both religions with which he disagrees, "they also have amazing parts that I can totally relate to. … I have read the Bible. In fact, we've even sat here in London and for months, we sat after dinner and just read a chapter, the family, so that the children would know the Bible. It's a great book."

At the same time, he mentions the influence of public intellectual and social critic Noam Chomsky. He recalled the story Chomsky describes as a defining moment when, as a youngster, he failed to intervene when a fellow student was being bullied.

The lesson Gordon takes from all of it is "you have to intervene for the underdog," a lesson that requires one "look at the power relations, the political relations, and to be with the underdog, to be with the weak."

The lesson Gordon takes from all of it is "you have to intervene for the underdog," a lesson that requires one "look at the power relations, the political relations, and to be with the underdog, to be with the weak."

Peter Walshe grew up in South Africa and became both student and analyst of that country's apartheid structure and the liberation struggle that led to its demise. He gave Notre Dame's Sheedy Lecture in 2004, and it is easy, from several passages, to detect the influence that worked on Gordon.

"I believe there is an ineradicable tradition of protest, of moral imagination, perhaps even of divinely inspired discontent. As I have come to understand this tradition," he said, it had "components that form powerful 'magnetic' forces moving our moral compass towards greater equality." He later states, "I believe that my most important role as a teacher is to draw the attention of students to this tradition of dissent."

In the case of one student, at least, he seems to have succeeded.

Neve Gordon wrote columns for NCR from 1996 through 2009. In January 2009, Gordon and Yinon Cohen, professor of Israel and Jewish studies at Columbia University, wrote a column that ran in NCR listing three components for a two-state solution to the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict. (Courtesy of Neve Gordon)

Tolerance erodes

In January 2009 Gordon, then chair of the department of politics and government at Ben-Gurion University in Israel, had just published Israel's Occupation, a history of Israel's occupation of the West Bank and Gaza. In January of that year, as Barack Obama was about to begin his first term as president, Gordon and Yinon Cohen, professor of Israel and Jewish studies at Columbia University in New York, wrote a column that ran in NCR listing three components for a two-state solution to the ongoing conflict. Their plan required Israel's withdrawal to 1967 borders; division of Jerusalem so that each side could control its religious sites; and right of return for all Palestinians with certain stipulations.

That was a glimmer of hope, perhaps, however short-lived. The previous year he had written a piece headlined, "Why I live in Israel: A frequent critic of his country says what he loves about it too." It too provided a look at why he held his "passionate commitment" to the country. "No doubt having been born and raised in Israel makes me feel most at home there. My family and friends live in Israel. I like the smells and the tastes, and I am not surprised or taken aback by the forthrightness, the occasional arrogance or the cynical humor that characterize many Israelis."

Advertisement

All of that, however, is not extraordinary to anyone who loves their country of origin, he wrote. Nor is the "materiality of the place" the reasons for his love of Israel. "The Wailing Wall simply does not do it for me. … Rather, my feelings derive from what one might call the country's soul, by which I mean its history, people and cultural idiosyncrasies."

Among those cultural idiosyncrasies, he mentioned was "the range of public debate in Israel, which is much broader than in most countries." He noted that his university had received several complaints about his point of view. Even though his students might disagree with him, he wrote, they "are familiar with and have been exposed to views like mine and consider them part of the legitimate discourse."

That optimism would not last. Gordon published two more books with political anthropologist Nicola Perugini: The Human Right to Dominate, and Human Shields: A History of People in the Line of Fire.

He is also widely published in general circulation newspapers and magazines and over the years has held visiting professorships at University of California, Berkeley, University of Michigan, and Brown University.

A tipping point

While his writing was controversial in many Jewish circles internationally, a piece he wrote for the Los Angeles Times in 2009 describing Israel as an apartheid state and supporting an international boycott of Israel was for many, including the administration of Ben-Gurion University, beyond the limits of their tolerance.

In the piece, Gordon acknowledged the boycott, divestment and sanctions campaign was an extreme measure. "It is indeed not a simple matter for me as an Israeli citizen to call on foreign governments, regional authorities, international social movements, faith-based organizations, unions and citizens to suspend cooperation with Israel. But today, as I watch my two boys playing in the yard, I am convinced that it is the only way that Israel can be saved from itself," he wrote.

Neve Gordon currently serves as professor of human rights law at Queen Mary University of London. In 2009 Gordon taught at Ben-Gurion University in Israel. But that year he wrote a piece for the Los Angeles Times, describing Israel as an apartheid state and supporting an international boycott of Israel. For the administration of Ben-Gurion University the essay was beyond the limits of their tolerance. (Courtesy of Neve Gordon)

The essay sparked outrage among some supporters of Israel and led to a fierce debate over academic freedom. Israel's minister of education demanded that Gordon be fired. His department supported him and his right to speak his views "and basically notified the president at the time that no one would replace me as head." However, "there was a decision that I would continue for another year and then resign. And that's what I did."

He and Rottenberg had been co-founders, with several friends, Palestinians and Jews, of a Jewish-Palestinian school in Beersheba in 2006. They named it Hagar, after the Genesis figure who was the concubine of Abraham and mother of Ishmael, thus an important figure to Judaism, Islam and Christianity.

They felt it could model a kind of future living together. "After 10 years, it became kind of clear to us that while it was an important project, you cannot create kind of non-apartheid islands within an apartheid. That does not really work." In addition, he said, the Ministry of Education would not allow them to continue that kind of education beyond elementary school.

Given the choice, he said, he would write the same piece. Boycott, divestment and sanctions, he said, are nonviolent actions. Even today, he said, the question would remain: "Do I want to raise my children in an apartheid regime? I don't. And that became the ultimate question of leaving."

'Do I want to raise my children in an apartheid regime? I don't. And that became the ultimate question of leaving.'

—Neve Gordon

While he returns to Israel to visit aging parents, he said he and his partner have paid a price. "Our jobs aren't as good. I'm away from my family, from my culture, from my language. So it is a kind of self-imposed exile."

The tolerance for dissenting views in Israel has severely narrowed over the decades, and following Oct. 7, he said, tolerance has decreased even further.

He thinks this current war will be a defining moment. In that earlier moment of the second intifada, the moment that was transformative for Gordon personally, he also realized a more pragmatic point. Beyond empathy for Palestinian suffering, there was in his estimation another sobering political reality: Israel's violent measures don't work.

In the establishment of Israel in the post-World War II era, an effort he describes as a way to resolve the crimes perpetrated against Jews on European soil, he sees Palestinians paying the price for Europe's crimes.

Neve Gordon is pictured in front of a video setup. While he returns to Israel to visit aging parents, he said he and his partner have paid a price. "Our jobs aren't as good. I'm away from my family, from my culture, from my language. So it is a kind of self-imposed exile." (Courtesy of Neve Gordon)

"The Jews create a state that the whole idea behind it is that it will serve to protect Jews against persecution and against antisemitism." Instead, he said, "We have the situation where the least safe space for Jews to be is Israel. I mean, that's an empirical observation. And the nation-state that privileges the Jew becomes or is a form of racialized governance, right?"

Does he envision ever returning to Israel? He won't say it will never happen, "but I know that it's not anywhere in the future that you can see."

While far from the scene, he had personal connections to the horrific attack by Hamas. "I knew four people that were killed on that day. One of my former students, a friend and teacher from the school we established and his wife. Their daughter went to the same class as my son. So, we know a lot of people that were caught in this."

Why isn't he among those wishing for retribution?

"Because we have to change the hard drive. This hard drive of violence is leading nowhere. You know, it's clear, and we need to change the whole paradigm under which we see this conflict." He is not a pacifist, he said, but "violence is not going to achieve anything. It's clear Israel's been living on its sword from the moment it was established. And that has led to more and more violence."