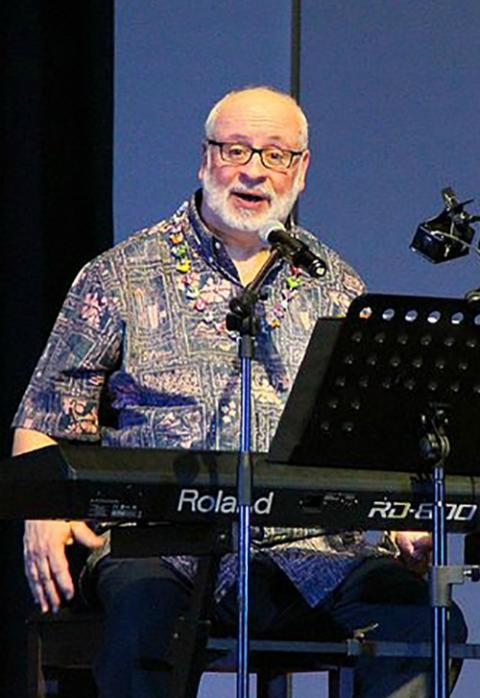

Margaret Hillman cantors at St. Thomas More Catholic Church in Sarasota, Florida, this fall. (Alex Dilan)

This summer while cantoring during Mass, Margaret Hillman was overcome by traumatic flashbacks that caused her to have panic attacks while singing music by Catholic composer David Haas.

Hillman's flashbacks were triggered by a press release from the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) that supported the reports that the advocacy group Into Account collected from several women accusing Haas of sexual and spiritual abuse. Hillman said the allegations "felt so familiar."

Two weeks later, Hillman described sexual abuse by Haas in her own report with Into Account, an organization that supports survivors of sexual abuse in Christian contexts. Hillman, a 53-year-old musician, serves as cantor, choir member and assistant with the youth choir at St. Thomas More Catholic Church in Sarasota, Florida, and cantor at Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church in Venice, Florida.

Hillman also asked Venice Bishop Frank Dewane to tell parishes in the diocese to stop playing Haas' music at Mass and was pleased the bishop responded by sending a letter to all parishes to put a moratorium on Haas' music.

This July, Hillman, fellow survivor Susan Bruhl and former Haas colleague Laurie Delgatto-Whitten sent letters to all dioceses requesting to publicly ban Haas' music from liturgies, to ban him from working in the dioceses, and to reach out to other potential survivors of abuse.

Delgatto-Whitten signed the first letter, which was emailed to all dioceses on July 4. On July 26, due to the lack of response (only five bishops responded, Delgatto-Whitten said), Bruhl and Hillman co-authored another letter speaking on behalf of more than 40 survivors who have alleged abuse by Haas.

At press time, of the 174 dioceses contacted, 35 responded that they will ban Haas and his music, 37 responded to the letters but did not make a firm commitment to fully ban his music, and 102 have not responded to the women, according to documentation that Delgatto-Whitten shared with NCR.

Hillman said she first met Haas when she was 14, at a music workshop for cantors. In the winter of 1986, when Hillman was 18, she and her mother attended a concert after-party in Rhode Island where Haas suggested Hillman might like the liturgical music program at the University of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minnesota, offering to give her a tour of campus. After the party, Hillman wrote in an email to NCR, "he spun me towards him and kissed me without warning."

Margaret Hillman at age 18 (Provided photo)

Hillman stated that they spoke on the phone several times, and she sent a voice recording to Haas at his request, putting her at ease for the upcoming visit.

Hillman said that one night during the tour of St. Catherine's, as she was staying on campus, Haas came to her hotel room* with dinner, and wanted to eat in her room.

"As a college student, this still seemed non-threatening," Hillman wrote in an email. "At some point, he kissed me again. When I did not want to proceed further, he became very angry and accused me of misleading him and acting like a child. At some point, I complied with his sexual demands. I was 18, alone in a strange city a thousand miles from home. I did not see any other options at that moment."

Stephanie Krehbiel, executive director of Into Account, said that following its initial report this spring, the group has been overwhelmed by stories like Hillman's. Into Account has been assisting survivors, and informing institutions where Haas has worked with the hope of preventing future abuse.

On Oct. 1, Into Account released a new 22-page report compiling 44 women's harrowing accounts of sexual and spiritual abuse by Haas, spanning 41 years. Allegations begin in 1979 when Haas was a seminarian accused of raping at 13-year old girl, who was shamed by two priests and the archbishop when she reported the abuse, according to Into Account.

Krehbiel said many women reported that Haas would give them the impression he was an access point for their professional careers in exchange for sexual acts.

She said many survivors reported that having to play his songs was retraumatizing.

The Into Account report says of Haas:

He wrote sacred music for women he was actively abusing and in such songs chose to express theological themes designed to disempower them. Haas blended religious devotion and abuse in a way that increased the vulnerability of his spiritually sincere targets and guaranteed that it would be difficult for survivors to disentangle themselves from his abuse without spiritual confusion or distress.

Krehbiel said it is hugely important to ban Haas' music because "so many of these women have jobs in liturgical music and have to deal with the violence that happens to their spirit every time they have to perform his music."

An excerpt from the July 26 letter signed by Hillman and Bruhl, e-mailed to all diocese in the U.S., reads:

Many victims told trusted mentors, priests, even bishops and archbishops. They told conference organizers and music publishers. They told friends who tried to advocate on their behalf, who were shot down or ignored, who are now blaming themselves for not doing more. They told friends of their abuser, hoping they could appeal to conscience. Yet Haas never faced any consequences. IntoAccount continues to receive and respond to additional reports almost daily.

Krehbiel said that accusations of abuse include aggressively forcing women into walls and groping them, forced oral sex and forced intercourse, cyber-stalking, suddenly exposing penis and masturbating in cars and hotel rooms, and threatening to "out" someone's LGBTQ-status in retaliation for reporting his behavior. Early reported incidents include rape and assault of children age 13-17, and the Into Account report suggests Haas learned to focus attention on "adult" women after their 18th birthday.

Krehbiel said that she thinks that the abuse went on for so long because of the Catholic Church's subjugation of women and the secretive nature of sex within the church.

"When women are put in positions of basically being extorted for sex, the Catholic Church is not a safe place to come out as a victim of that abuse," Krehbiel said.

The Into Account report adds, "Haas was able to benefit from the restrictive sexual ethic of the Catholic Church, particularly its intolerance for LGBTQ+ relationships and its requirement of celibacy for priests."

Delgatto-Whitten, who has been assisting Hillman and Bruhl with sending letters to dioceses and collecting their responses, met Haas in 1999 while working at Music Ministry Alive!, a summer institute for high school students interested in liturgical music ministry, created and run by Haas.

Laurie Delgatto-Whitten with her goddaughter during the 2018 March for Our Lives in downtown Houston (Provided photo)

Delgatto-Whitten said she left the program after two years, due to Haas refusing to listen to concerns she brought to him about appropriate pastoral youth care. She became a point person for survivors after interacting with them on Facebook this summer.

Kathy Leos, a 62-year-old choir teacher at Bishop Lynch High School in Dallas, is one of the survivors who reached out to Delgatto-Whitten and one of the 44 women named in the Into Account Report. Leos said she had a 37-year relationship with Haas, ranging from "friendship" (Leos noted air quotations) to many abusive incidents, including spiritual abuse.

Into Account's Oct 1 report details instances of spiritual abuse connected to Haas' music, saying: "By using sacred music as a medium for grooming and abusing girls and women, what Haas made manifest through his sacred music was often traumatic, misogynist violence, disguised as the inbreaking of the kingdom of God.

Leos met Haas in 1984. During the summer of 1985, while attending the convention of the National Association of Pastoral Musicians, Leos said, she felt flattered to be part of Haas' "inner circle," yet also felt demeaned when asked to run errands for him, a pattern that continued throughout their relationship.

"I was unhappy that my talent as a musician and a choral director never seemed to be recognized or asked for — but my hotel room information was frequently requested," Leos wrote in her Into Account report.

Leos said she was privy to some of the earliest versions of Haas' hits.

"I heard 'We Are Called,' 'You are the Voice' and many other songs before most folks, making me think I held a special place in his life," Leos said.

Haas invited Leos to recover from her vocal cord surgery in fall 1985 at a mutual friend's house where he also was staying. Leos wrote that multiple times she awoke to Haas climbing into bed with her, whispering that he wanted to cuddle and trying to touch her inappropriately.

"I had no voice, because of the surgery, so there was literally no way for me to say no," Leos wrote.

Leos reported several other incidents of sexually aggressive behavior by Haas, including in approximately 2008 an attempted sexual assault in a hotel room in Dallas.

Most recently, Leos said, she experienced spiritual abuse from Haas after she and her husband divorced four years ago. Leos said she was in a vulnerable place when she confided in Haas, who first was consoling, sending prayer books and cards, but quickly turned to "sexually inappropriate comments," Leos wrote in her Into Account report shared with NCR.

In February 2019, Leos said she realized the extent of Haas' abusive behavior toward her.

"It was like being the proverbial frog in that pot of water. The heat was so slowly intensified, that I never even realized what was happening to me over the years," Leos wrote in her Into Account report.

Catholic composer David Haas in 2016 (CNS/Titopao, CC BY-SA 4.0)

When asked to comment on the accusations alleging sexual and spiritual abuse of adult women, Haas provided a response emailed to NCR through his attorney, Alan Eidsness on Sept. 24:

I want to reiterate my full apology of July 9. To anyone I have harmed please know that I take full responsibility for my actions and am truly sorry. I am continuing with professional intervention to help me face and understand how my actions have violated your trust. I have continued to give prayerful thought to my actions and ask for forgiveness from anyone I have harmed — those individually and those in the church community who have been harmed because of these accusations. I believe in the God who loves all of us and pray for anyone I have harmed and pray for God's forgiveness.

Haas' music has been dropped by GIA Publications, Oregon Catholic Press suspended ties with him, and the National Association of Pastoral Musicians rescinded the Pastoral Musician of the Year award it gave him in 2004. Delgatto-Whitten said most institutions recognized the seriousness of the accusations, and it is the bishops who have largely not responded.

However, survivors have appreciated "pastorally sensitive responses" from some bishops.

Bishop William Wack of Pensacola-Tallahassee, Florida, wrote in an email that was shared with NCR: "Thank you for your email, and thank you for your courage and resilience. Thank you for sharing your story of abuse and assault by David Haas. I do believe you and I grieve with you. I am so sorry."

Wack goes on to say: "I mentioned the fact that Haas receives royalties from his songs, and that hearing his songs may trigger anxiety and pain in some people; but I hadn't thought of the fact that — as you noted below — 'Haas used his music as a way to enable his pattern of abuse.' This is one more reason to silence his music."

Other bishops dismissed the survivors, including Bishop Richard Stika of Knoxville, Tennessee, who wrote in a July 19 email shared with NCR, "I believe that a person has a presumed innocence until the person either admits guilt or guilt is proven. Until that time, I don't plan on taking any action."

When asked for further comment, Stika wrote in an e-mail to NCR on Sept. 4, "I plan on asking all the music ministers, both women and men. I know the music is popular in a few parishes. I have not been following any of the latest information. So until I hear from the music ministers, I plan on no action. I always like to seek input from the good people of the diocese."

Krehbiel said that claiming innocent until proven guilty is "a very convenient way to say this is not our problem, and a very convenient way to let over 40 women know they can't be trusted to tell the truth."

Leos called the innocent-until-proven-guilty response "a straw man."

Hillman noted that survivors have also been pained by the reaction of "people in the pews."

"The thing I want people really to understand — a lot of people are saying things like 'oh the music is so beautiful' or 'I love this song' but we're experiencing flashbacks and panic attacks," Hillman said. "And they need to think about that. It's not about them. It's not. We're not trying to take anything away from them. There is so much beautiful music out there."

[Sophie Vodvarka is a freelance writer in Chicago. Follow her on Twitter at @SophieVodvarka.]

Advertisement

*This article has been edited to correct the location.