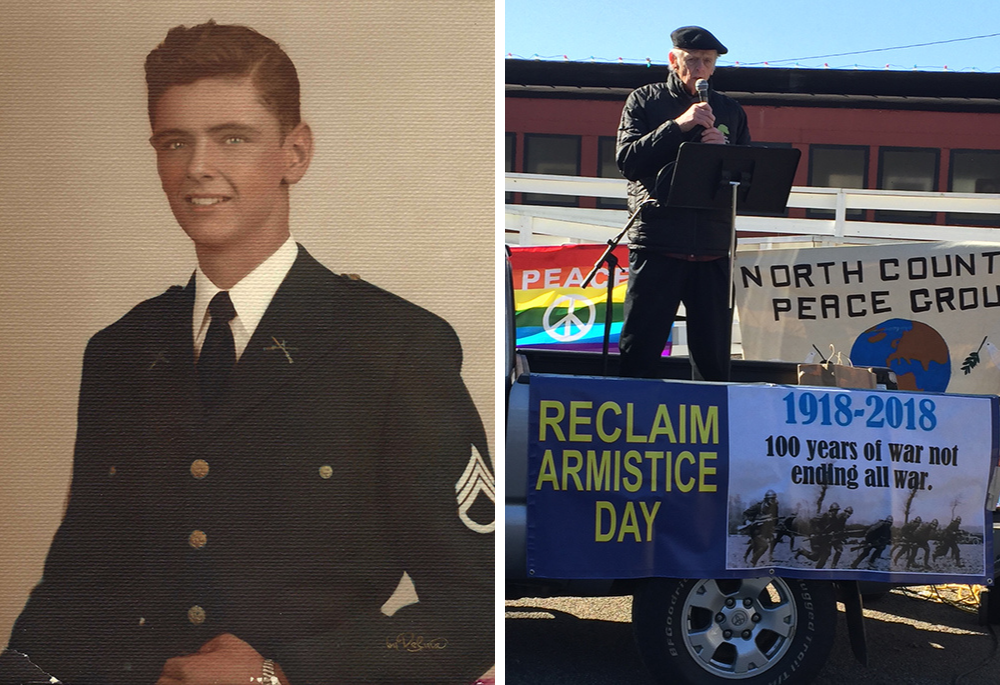

At left, Bill McNulty is pictured in a school portrait from St. Francis Xavier Military High School in New York City, where he was part of the ROTC program; in a 2018 photo (right), McNulty speaks at a gathering marking the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day, held in Port Jefferson, New York. (Courtesy of Bill McNulty and Myrna Gordon)

He marched with Occupy Wall Street and went to jail for crossing the line at the U.S. Army's School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia. He disrupted a military recruiting event by reading aloud the names of fallen soldiers. With two of his children, he planted a Veterans for Peace flag atop a Colorado mountain "to raise the experiences of veterans sharing the horrors of war." He has demonstrated at the Pentagon, CIA headquarters, the Trident submarine manufacturing center and Griffiss Air Force Base, to name a few.

At age 88, Bill McNulty is an American peace movement long-termer. A retired teacher, Veterans for Peace member and former U.S. Army artillery officer, he's a legend on Long Island, where he hosts his 28-year-old political commentary radio show on WUSB 90.1 FM. His opposition to militarism, economic disparity and U.S. foreign policies of violence and domination brought him across the country where he met other long-termers like Philip and Daniel Berrigan, Liz McAlister, Charles Liteky and Daniel Ellsberg.

But activism came slowly to McNulty, who was in his 50s before he emerged from what he called his "years of complacency" when he followed without questioning the tenets of church (Roman Catholicism) and country. A 1996 Long Island newspaper profile described him as "tall, craggy, Lincolnesque, Republican and respectable, nobody's image of a typical peace demonstrator."

He joined ROTC programs at his Catholic military high school and at Fordham University, and upon graduation from Fordham was commissioned a second lieutenant and sent to Fort Sill in Oklahoma. After active duty, he served in the Army Reserves until being honorably discharged in 1964.

"Never did I give serious thought to the fact that the training I was receiving might bring me to kill someone or be killed myself," he said during a recent interview at his Setauket home. "That's the way we were back then. Obedience, duty and responsibility were woven together into a comfortable blanket of acceptance."

That changed when Operation Desert Storm got under way in 1991 with a massive U.S.-led air offensive to expel Iraqi forces from Kuwait. For McNulty it was a defining moment, the final piece of a puzzle of past events he'd paid scant attention to, like U.S. intervention in Central America a decade earlier, though he remembers telling his wife Carol, "I don't know what's going on down there but I am pretty sure U.S. involvement is about protecting someone's money."

'That's the way we were back then. Obedience, duty and responsibility were woven together into a comfortable blanket of acceptance.'

—Bill McNulty

He started reading articles by thinkers such as U.S. diplomat George F. Kennan, eventually agreeing that the real objective behind America's military actions overseas was safeguarding U.S. financial interests and the coffers of war-profiteering corporations.

"It was an epiphany," McNulty explained. "As Kennan said then, we were a country representing 6.3% of the world's population while controlling about 50% of its wealth, and the day would come when we would have to deal with that disparity in raw power concepts."

Outraged, he took his fury to the streets, protesting on Long Island and elsewhere. He visited war tax resisters, attended the trials of anti-war and anti-nuclear activists, and traveled to Haiti where he saw "what poverty and exploitation look like in the despairing eyes of the poor."

Years later, it was the eve of the 1996 annual vigil to close the School of the Americas (or SOA), a U.S. taxpayer-funded training center for Latin American military in Fort Benning, Georgia, since renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation. McNulty stood in a circle with others considering acts of nonviolent civil disobedience at the base the next day. When it was his turn to speak, he announced he would risk arrest but needed to say why.

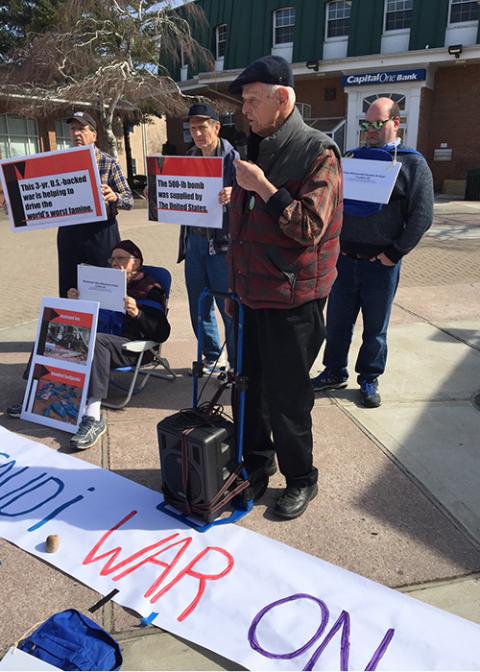

Bill McNulty speaks at a protest at a U.S. Army recruiting center in Patchogue, New York, to illustrate the alleged U.S. role in an August 2018 air assault on a Yemeni school bus. (Courtesy of Myrna Gordon)

McNulty did what he does best: He told stories. One about finding the name of 1960s civil rights worker Andrew Goodman chiseled in concrete on a bridge near the upstate New York Goodman family home. Another about the night his friend and SOA Watch founder Roy Bourgeois went to the school's barracks and blasted a recording of Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero ordering Salvadoran soldiers, some SOA graduates, "to obey a higher call and stop killing your countrymen" right before Romero himself was assassinated.

His third story centered on his observation that the Indigenous people who had conducted that night's pre-vigil ceremony seemed to embody the higher call that Romero spoke of. The final story was about watching protesters get arrested for blocking buses carrying students to their senior prom at the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum.

"I had seen what other people were willing to do," McNulty said. "Those connections meant I had to act on behalf of the victims of the SOA just like Andrew Goodman had been a victim of racism, murdered and buried in a dike in Mississippi."

That year McNulty was arrested for crossing the line at SOA, though released with a warning not to return for five years. But the following year, he trespassed again, was charged as a repeat offender and sentenced to six months that he served at a federal prison in Minersville, Pennsylvania.

Which brings him to another story.

"On my first day of prison, I was asked what my occupation was. I said I'd been a teacher, a carpenter and was involved in church ministry. They sent me to the prison psychologist who asked me two questions: 'Do you think you are Jesus Christ?' and 'Do you have a messiah complex?' When I said no, he asked, 'What are you in here for anyway?' That's when I gave him the whole SOA story."

Advertisement

His Catholic faith remains strong though he has had run-ins with right-leaning priests and parishioners and was considered too radical for a church peace and justice group. He admonished his pastor, a "firebrand" on abortion, for not expressing similar concern for migrant children separated from parents at the border. In prison he led Bible study and urged inmates to challenge the Catholic chaplain ("more a prison guard than a priest") who had rebuked them.

These days he takes his pulpit wherever he goes. There is no one he won't approach. Not the people he sees in the supermarket, in doctors' offices, even in the hospital. Not the Army major he met during an SOA protest on the Capitol steps.

"I asked him if he knew of Smedley Butler, a military hero and retired Marine major general who in retrospect saw his whole career as one serving the protection of money," McNulty said of that encounter. "The major said, 'I never heard that before,' and walked away."

McNulty often quotes the fictional Irish bartender Mr. Dooley who famously opined that "the job of a newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable."

"I try to empower folks to examine different points of views, to wean them away from conventional wisdom and placing their faith in people and institutions that haven't earned it," McNulty explained.

The war against the poor he first recognized in Central America continues, but like all wars we wage "eventually they come home," McNulty believes. "Now we are either on the red team or the blue team. Now we are told that our enemy is a gay person, a transgendered person, Muslim or Black or a woman. Or the enemy turns out to be the dissenter, the one who doesn't agree."

'I try to empower folks to examine different points of views, to wean them away from conventional wisdom and placing their faith in people and institutions that haven't earned it.'

—Bill McNulty

Still, he's optimistic. He equated his hope of "getting 100 tulip bulbs into the ground and seeing them come up in the spring" to his hope that there will be "transformation among people."

He imagines that if that can happen to him, it can happen to anyone.

Of course, you could end up "like the guy who was flailing away at the veins of a windmill though even he had a friend, Sancho, who helped him, and all the people he affected with his crazy ideas," McNulty said.

And if you're lucky, like the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., you make it to the top of a mountain where you get a glimpse of what could be.

"On the other side is beloved community," McNulty said. "Then the question is, how far will you go to bring that about? You may think it's beyond you but you can't let that stop you.

"And if you can't begin at the most extreme place then you have to start in the supermarket."