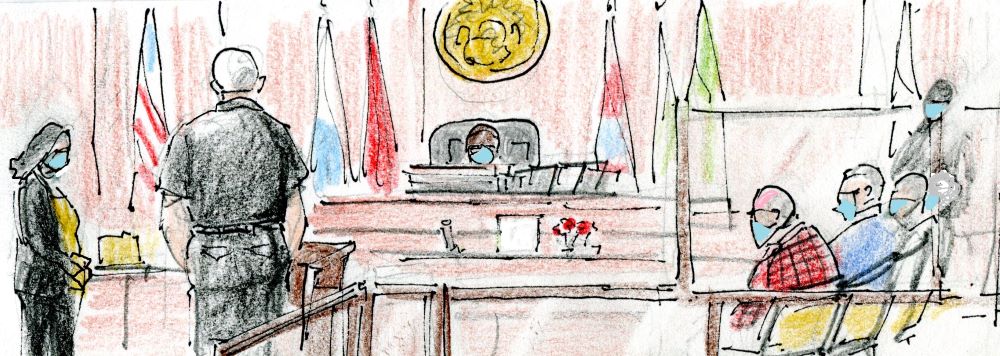

In a sketch of the courtroom Feb. 18, the prosecutor, Jesse Sendejas questions Lt. Michael Clark. Judge Ardie Bland presides, while defendants (from left) listen: De La Salle Br. Louis Rodemann, Jim Hannah, Tom Mountenay and Brian Terrell. (Courtesy of Pat Marrin)

Kansas City Municipal Court Judge Ardie Bland suspended six-month jail sentences for four anti-nuclear activists Feb. 18. (Thomas C. Fox)

With nations warring, arsenals stocked with nuclear weapons, four peace activists on trial in Kansas City, Missouri, in February offered what they said was a way out of growing madness: nonviolent resistance.

A judge, faced with ruling on trespass offenses at a local nuclear weapons manufacturing plant, appeared persuaded with their cause and suspended six-month jail sentences while praising the activists for attempting to change the world.

"While in the eyes of the law you are guilty, I recognize that there is a higher power that compelled you to act," Kansas City Municipal Court Judge Ardie Bland told the men.

"One thing I'm always reminded of is that in the eyes of the law, Martin Luther King was seen as a criminal," Bland said. "So, I'm of the understanding that oftentimes the law is not in your favor. However, if King and other people like him didn't do what you people are doing, nothing would ever change."

Kansas City has been a hot point of nuclear weapons protests going back to November 1984 when four protesters – Oblate Fr. Carl Kabat, his brother, Oblate Fr. Paul Kabat, Helen Woodson and Native American Chief Larry Cloud-Morgan — broke into the grounds of a Minuteman 2 nuclear missile silo east of the city, and damaged the concrete lid over the silo with sledgehammers and a jackhammer. Their original sentences were from 18 to 25 years in prison.

During the past dozen years, local anti-nuclear weapons activists have gathered repeatedly to protest the continued production of new nuclear weapons. Each Memorial Day, scores march on a plant, called a National Security Campus, south of the city, which procures and manufactures 85% of the nonnuclear components of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The plant covers grounds larger than the Pentagon, employs some 6,000 people, and runs on a $1.2 billion annual budget.

Members of PeaceWorks Kansas City, a local peace group, have organized Memorial Day protests at the plant for the past decade. Scores join in; a handful typically cross onto the plant's property, walking into the hands of plant security guards and local police, sometimes in black riot gear. (Full disclosure: I have participated in these protests and three years ago crossed the line and was arrested.)

Four of five protesters who trespassed last Memorial Day — Tom Mountenay, Brian Terrell, Jim Hannah and De La Salle Br. Louis Rodemann — faced Bland Feb. 18, each making the case to abolish nuclear weapons before they abolish humanity.

What characterized their protest and court actions was the purposeful respect they showed to those who disagreed with them, a core element of vows each had taken to practice nonviolence.

"The intent is to practice nonviolence. Loving one's so-called enemy involves really respecting that person," said PeaceWorks co-chair Henry Stoever, who faced another judge Feb. 23 for the same trespassing act.

Kansas City nuclear plant demonstrations occur only after protesters inform the police of their plans, sharing their agenda and telling them what to expect —including how many people plan to risk arrest by crossing the property line.

Stoever, a retired attorney, makes the point of opening all communication channels, giving plant security guards and local officers his telephone number and email address. He has shared Christmas and Easter greeting cards with a plant security guard and he and his wife, Jane, on at least one occasion, have dined with a plant security guard.

Communication and respect are essential for successful nonviolent action, Stoever told NCR.

Over the years, suspicions about the protesters from police have waned. On one recent particularly hot Memorial Day, the police passed out cases of bottled water to the protesters. Last Memorial Day, after Hannah had crossed the line and put his hands behind his body to be cuffed, he told one police officer, a woman, that his arm hurt.

The officer cuffed only one hand, though Hannah, not wanting to expose the action, played along, keeping both hands behind his back during the 45-minute booking at the plant.

Advertisement

At the Feb. 18 trial, the prosecution's sole witness, Lt. Michael Clark, a plant security guard, told Bland he had nothing but respect for the demonstrators. He shook hands with each of them, in effect, becoming a witness for the defense.

Before passing his verdict, Bland, in an unusual move, gave the demonstrators five minutes each to explain the motives behind their actions.

The last to speak was 82-year-old Rodemann. Shoulders hunched and wearing a faded, checkered shirt, he began reading from a single piece of paper he had carried in his pocket.

"Over half, 53% of the US discretionary budget, is allocated to the plans and preparation for war, our carrying out these plans, and addressing the long-term physical and mental effects of our veterans," Rodemann said. "Every budget is a moral document! Under these criteria, our country, the United States of America stands indicted: sinful, guilty, immoral!"

An American flag immediately behind him, Bland's facial reactions, if any, were obscured by a KN95 mask.

Rodemann went on to say he had taken a personal vow of nonviolence and it included eliminating the causes of war "from my own heart and from the face of the earth."

Bland then asked the defendants if they had been involved in other public protests, triggering each to list scores of social justice issues that had moved them to demonstrate. Bland responded: "Then you have not just plucked this protest out of the air. It shows you really cared about people and responding to human needs."

Bland said he was torn between "enforcing civil law and doing the right thing."

"The supreme court of a high power is always going to have you do what you think you need to do that is right," said the judge. "I have no intentions of having you ever serve a single day in jail."

Bland asked the men to pray for him and for the justice system "to do the right thing."

If there was any question in the minds of court onlookers the men had made the impact they intended, it seemed to disappear when Bland invited each, at trial's end, to come to the bench and bump fists.