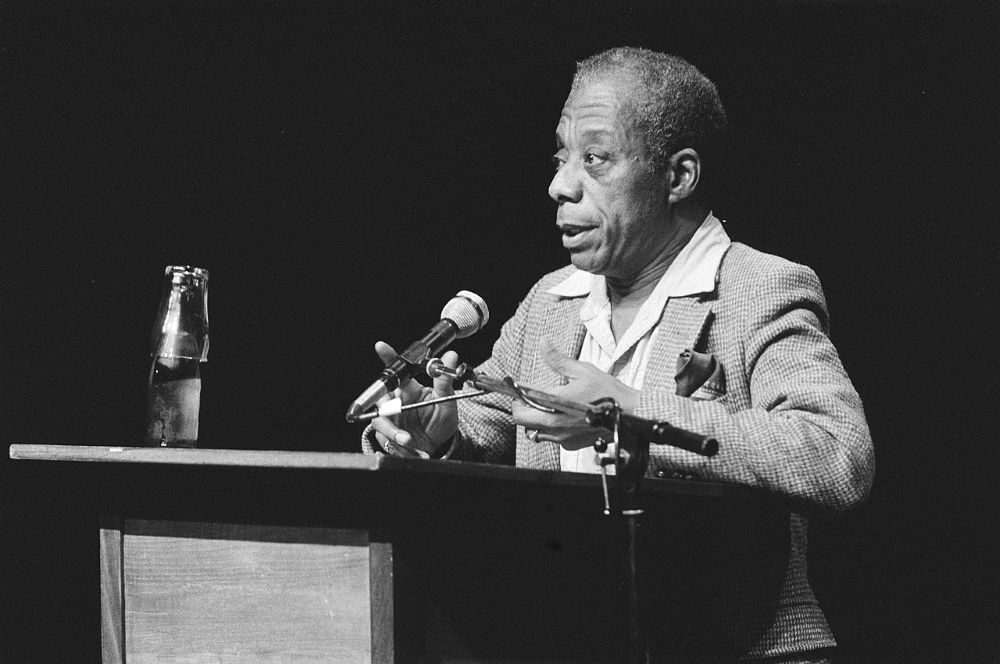

The influential novelist and essayist James Baldwin (1924-1987) speaks in Amsterdam in 1984. Giovanni's Room was published in 1956. (Wikimedia Commons/Fotocollectie Anefo Reportage)

Sixty-five years after its publication, James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room feels as trailblazing as ever.

The novel was published in 1956 — a particularly impressive feat during the mid-19th century when homosexuality was still considered a mental illness in the United States — and goes beyond the sterile categories of LGBTQ+ identity politics and towards the messiness and risky nature of human attraction and desire.

Our protagonist David meets Giovanni at a local gay bar. David has proposed to his girlfriend Hella, who goes off to Spain to consider his proposal. He is instantly attracted to Giovanni and feels a connection. When Giovanni looks at him, David feels as if no one has truly looked at him before.

Their feelings soon become complicated, however, as David feels that his desire for Giovanni could be dangerous. One night, a zombielike figure warns David he will burn in Hell if he gives in to his desire for Giovanni. By zooming in on David's inner turmoil and anxiety about his desire for Giovanni, Baldwin helps us understand the daily mental, physical and emotional difficulties that LGBTQ+ people endure in the fight against internalized homophobia and heteronormativity.

To further illustrate David's internal conflict, Baldwin describes Giovanni's room, the setting of much of the novel, in great detail. The room on the outskirts of Paris is filled with yellowed newspaper, ripe with the sweet smell of stained wine and rotting potatoes. "It was not large enough for two," David says. "It looked out on a small courtyard. 'Looked out' means only that the room had two windows, against which the courtyard malevolently pressed, encroaching day by day, as though it had confused itself with a jungle." The room is small and constricting, a vivid metaphor for how Giovanni feels trapped within the limitations of a heteronormative world.

It is also the one, sacred space where David and Giovanni can safely, albeit briefly, express and live out their queer desires for each other. Giovanni's Room illustrates that many queer people live with daily fear, because as much as they work on overcoming internalized homophobia, deep down they know that the world is not made for them. Giovanni's room is the one place where they can seek refuge from the outside world's homophobia. While Giovanni was not physically imprisoned, Baldwin describes how claustrophobic the room feels. The same goes for the feeling of social claustrophobia that LGBTQ+ people feel living in a heteronormative society. Just as Giovanni was committed to remodeling his room, we, too, must continue to push the limits that heteronormativity places upon ourselves and our LGBTQ+ kin.

Since the book's publication, U.S. culture has changed in many welcome ways. The Supreme Court passed marriage equality in 2015. Hollywood offers increasing representation of LGBTQ+ people in popular culture. Films and TV shows such as "Love, Simon," "RuPaul's Drag Race" and the inclusion of a queer love story in "Atypical" encourage queer people to be proud of their sexuality.

From gay-friendly Masses in Midtown Manhattan to LGBTQ+ affirming podcasts, many Christians are working toward becoming more inclusive. The response has been varied, but many prominent Christian figures, like the rock group Switchfoot, have come out as explicitly supporting LGBTQ+ people,

Yet nuance is missing in many forms of allyship, from corporations to individuals — and this is why Baldwin's work continues to be a timely and necessary read for anyone trying to center and uplift the LGBTQ+ community.

Advertisement

The genius of Baldwin's storytelling is how he shows us the anguish beneath the joy of David and Giovanni’s love. David experiences cognitive dissonance. On the one hand he desires Giovanni, yet he also desires to be with a woman, any woman, to preserve his manhood and please his father. This cognitive dissonance — choosing between their inner desires and meeting social expectations — is what too many LGBTQ+ people still experience daily.

Baldwin, through visceral, cinematographic descriptions, ushers the reader beyond the performative corporate allyship decked in pink-washed, corporatized Pride campaigns and challenges us to center the activists who have fought against a homophobic society, the queer women and men who made it possible for us to walk with pride across rainbow paved crosswalks today.

Amid the cacophony of Pride parades around the world, it is easy to forget that the first Pride parades were anti-capitalist, grassroots protests led by Marsha P. Johnson, Silvia Rivera and other Black and Latina trans women.

You do not have to identify as LGBTQ+ to engage in this work. David empathizes with Giovanni not because he is queer, but because he loves Giovanni enough to enter his room — even though it's claustrophobic, stinky and messy. Giovanni invites David into his room so that he can destroy it and give him a new and better life — to participate in the labor of love.

We, too, can participate in the labor of love by being honest about the continued oppression that LGBTQ+ people face today, from employment discrimination, to visiting the doctor's office, to requesting housing loans.

Baldwin calls us past performative allyship, toward empathizing with the suffering and joy of our LGBTQ+ siblings in Christ. Just as Jesus entered into our world so that He could empathize with our human experience, so, too, does Baldwin invite us into Giovanni's room — to empathize with the pain and joy of the LGBTQ+ experience. To participate in the labor of love — recreating our world as we know it. Creating space, brick by brick, where all LGBTQ+ people have access to safety, emotional support and the ability to celebrate how they choose to express their sacred desires.