Nigerian patrol boat NNS Ibadan was captured at the declaration of independence of Biafra during Nigerian Civil War. The breakaway country lasted from 1967 to 1970. (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1967, a new country emerged in Africa from the hopes and dreams of the Igbo people of Nigeria who sought to create their hope-filled homeland. Sadly, it was not to be and in 1970, Biafra, as the country was named, no longer existed, crushed by the military might of its mother country Nigeria. Yet, many still believed in its possibilities.

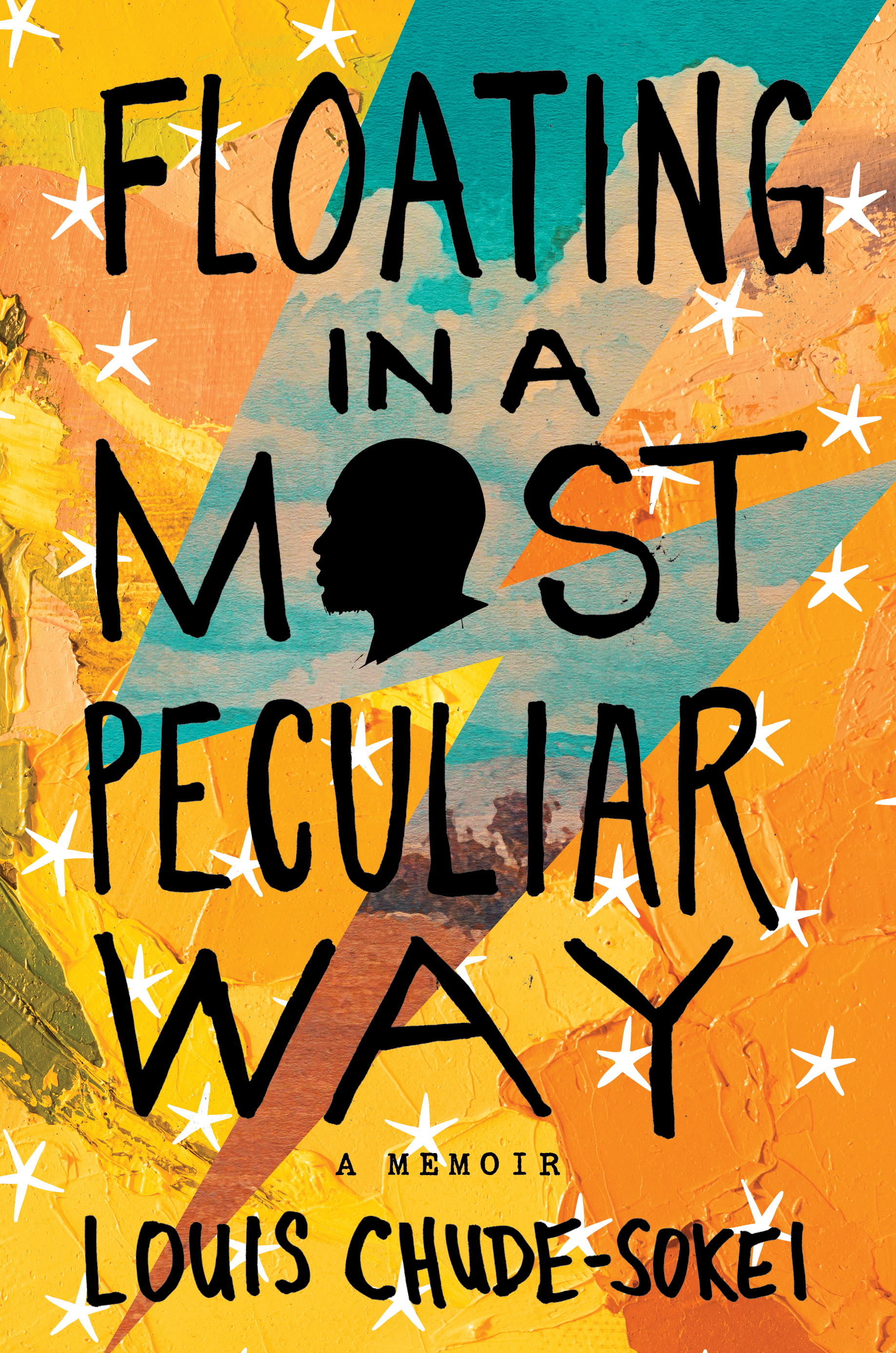

The country lasted only from 1967 to 1970 when it died, crushed by the heavy weight of the Nigerian military. A child was born at its beginning, however, a male child, to a Jamaican born mother and a Biafran father. His father, whose name is never mentioned, was seen as the hope of the people of Biafra but was killed in the bombing and fighting that personified the last days of the fledgling country. The child, Louis Chude-Sokei, "the first son of the first son," was seen as the continuation of that hope, even though he was whisked away to Jamaica shortly after his birth and did not actually set foot in Africa until he was in his teens.

Chude-Sokei grew up in a strange mix of African, Jamaican and American influence. It was not clear to him or to others exactly who or what he was, and he spent most of his childhood trying to figure this out. The first part of his life was spent in a sort of orphanage run by Big Auntie and Uncle Daddy. All the children living there were expecting at some point or another to be summoned to wherever it was that their mothers lived. None had fathers, as far as they knew.

Their destinations varied; some were meant to return to Africa, others were heading to England or to the United States to live. America was seen with hope but also fear because it was seen as a place where people disappeared all the time, especially mothers. But they clung to their somewhat desperate hope in a future unknown but surely better than their present.

What did those names mean and what was his reality? He grew up searching for a song — a rock song, not an African one — that seemed to float in and out of his life. He first heard it while still in Africa, in a refugee camp. The song seemed to speak to him of his own ambivalent life, wandering through space and time seeking what, truly, he did not know:

This is Major Tom to Ground Control

I'm stepping through the door

And I’m floating in the most peculiar way

And the stars look very different today

—David Bowie, "Space Oddity"

This is Chude-Sokei's landscape, his world, which, at times, he seems to be observing from miles away, floating above and beyond the noise and confusion, the many aunts and uncles, his mother's illness, the hopes of so many invested in him. The music serves as an invisible backdrop, sustaining him as he floats on, above it all, still struggling to learn and understand who and what he is, where he belongs, why he is here,

Slowly, with the help of various uncles, his mother and the young men with whom he begins to bond in the U.S., Louis begins to see himself as someone, not something, as a young man who has a place in the world carved out by what is happening around him. He is an avid reader and becomes enamored of Malcom X, the Black Panthers and others who sought a better, a different world for people of African descent in the U.S. and around the world. He begins to feel a solidarity with other Blacks although he knows he does not fit the pattern of an American or a Jamaican or an African; he is a mixture of all of these and more.

The author shares the story of his life with clarity and honesty. There are parts that are clearly painful and confusing and others where he walks proudly, having succeeded in overcoming a serious obstacle or two. His life gives us insight into and, hopefully, empathy for Africans of whatever nation and African Caribbeans, seeking a place to call home, and struggling to understand the weird world of the United States, where persons of African descent are stereotyped in a way that affects all of us, regardless of country of origin. Only here does one's skin color take precedence over everything else in one's life. Learning to survive while maintaining a self-understanding that is very different from others, Black and white, is difficult but possible.

In the end, Chude-Sokei does more than survive; he forges his own successful path that leads him to a life he loves, as a university professor, as a Black man, as a pan-Africanist, as one at home finally in his own world.

Advertisement