"Baltimore in 1752," an 1817 illustration by artist John Moale and etcher William Strickland (The New York Public Library)

"We consider the establishment of our country's independence, the shaping of its liberties and laws, as a work of special Providence, its framers 'building better than they knew,' the Almighty's hand guiding them."

These words from the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884 formed the backdrop for Jesuit Fr. John Courtney Murray's brilliant and controversial effort to reconcile American ideas about religious liberty with Catholic teaching. Murray's work has been challenged in recent years, mostly from conservative scholars like David Schindler Sr., all of them questioning whether Murray's synthesis really worked.

A new book by Ave Maria University Professor Michael Breidenbach, Our Dear-Bought Liberty: Catholics and Religious Toleration in Early America, takes the Murray synthesis in a new and fascinating direction, arguing that Catholics were not merely the beneficiaries of the liberalism of the Founding Fathers. He insists that Catholic experience and thought laid some of the groundwork for the constitutional separation of church and state that was, and is, a central hallmark of the American polity.

Breidenbach's thesis is that controversies and negotiations about Catholics taking oaths of loyalty to the English, Protestant kings after the Reformation, combined with the exposure of Anglo-American clerics to Gallicanism and conciliarism, both led to the adoption of "antipapalism," a strict limiting of papal authority to the spiritual realm.

This separation of the spiritual from the temporal, he argues, laid the groundwork for what we know as the separation of church and state in the U.S. Constitution. And he provides a great deal of documentation to make his case.

The taking of oaths was no small matter. The Ark and the Dove, the ships that carried the first Anglo-Catholic settlers to what would become the colony of Maryland, "were already out of the mouth of the River Thames when, on October 19, 1633, the Privy Council ordered them back to port at Gravesend," he writes. "John Coke, the secretary of state, had heard a complaint that those on board had not taken the Oath of Allegiance."

Both King James I and his son Charles I required settlers in English colonies to swear an oath of allegiance to them and their successors. The founders and proprietors of Maryland, the Calverts, spent a great deal of time negotiating the actual terms of an oath that would not contradict their faith but would affirm their loyalty to the monarch.

Since Henry VIII had broken with Rome and demanded that all officeholders take the Oath of Supremacy — which oath Sir Thomas More refused to take, leading to his martyrdom — Catholics had sought a way to be loyal to both king and pope.

Henry's daughter Elizabeth had tolerated private Catholic worship for the first 11 years of her reign, after which a Catholic revolt in the north in 1569 was brutally suppressed. Elizabeth and her most ardently Protestant advisers ordered a crackdown on Catholics. In 1570, Pope Pius V issued the bull Regnans in Excelsis, excommunicating Elizabeth and freeing her subjects from any allegiance to the heretical monarch.

Here was a radical papal claim, the power to depose. Future iterations of the oath of allegiance to the monarch would include an explicit renunciation of that claim, and Catholics negotiated with the papal court for permission to swear such an oath. Leaders of the English Catholics, both clerical and lay, divided into more lax and more rigorous camps. The Calverts simply eliminated the controversial sentence denying the pope's authority to depose.

The Stuart monarchs did not want to push the matter too hard either. King Charles married a Catholic queen, and his sons and heirs both converted to Catholicism, Charles II on his deathbed and James II before he ascended the throne. It was complicated but, according to Breidenbach, all the back-and-forth over what could and could not be sworn served to demonstrate that the spiritual and the temporal powers of the papacy could be separated.

Advertisement

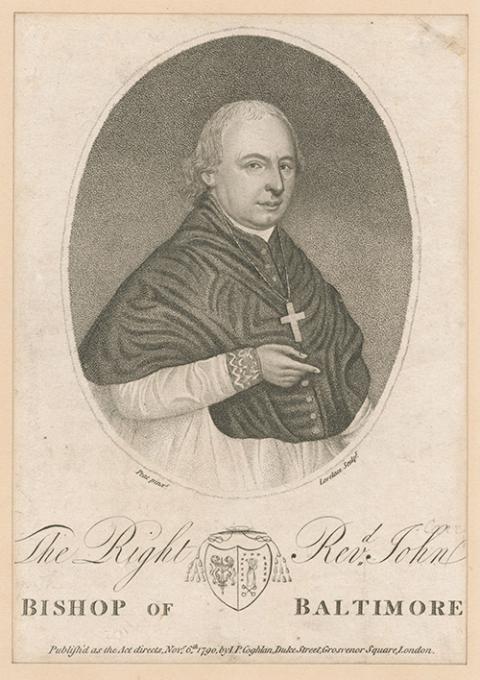

The Carroll family, which produced Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the only Catholic signatory of the Declaration of Independence, and John Carroll, the first bishop of Baltimore, educated their children at St. Omer in French Flanders, where most English-speaking Catholic gentry sent their children. The college was run by the Jesuits, the order most loyal to the papacy, but Breidenbach nonetheless demonstrates the degree to which John Carroll and others were exposed to Gallicanism and conciliarism. Gallicanism tried to limit papal influence over the Catholic Church in France and conciliarism emphasized the supremacy of councils over the papacy. Both Charles and John Carroll would cite these "antipapalist" arguments and texts when discussing the situation of Catholics in the new American republic.

This is quite new. In his book The Premier See: A History of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, 1789-1989, Thomas Spalding allowed that a "building block" of the Maryland tradition that John Carroll "would attempt to set in place was a measure of autonomy in the relationship of the local church to the Holy See." But Spalding also acknowledged, "Carroll had a great reverence for the person of the Roman pontiff and the throne he occupied as a symbol of unity."

Spalding further notes that Carroll's consecration as bishop at the chapel at Lulworth Castle in England coincided with a divide within the English Catholic community over the taking of an oath of loyalty to the government. "Though pressed by both sides, Carroll sidestepped commitment with consummate tact," he observes.

Spalding also relates tension in the young Baltimore Diocese between the ex-Jesuits and the Sulpicians, the latter being far more receptive to Gallicanism. But the struggle was mostly over their competing academies at Georgetown and Baltimore respectively, not about their ideological views on the relationship of the local church to the pope. Carroll, interestingly, also experienced frustration with his former Jesuit confreres who fought him over the disposition of property and other issues.

An 18th-century engraving of Bishop John Carroll of Baltimore (The New York Public Library)

Annabelle Melville's classic biography John Carroll of Baltimore: Founder of the American Catholic Hierarchy did not recount any conciliarist, still less Gallican, influences on the nation's first bishop. She does recall the times he had to defend Catholicism from those who misunderstood the church's teachings, and his early years as a Jesuit when the storm clouds over the order led to its suppression.

Most importantly, she shows how deeply determined Carroll was to avoid the introduction of many non-Catholic ecclesiological habits, such as allowing lay trustees to choose their pastor, into the life of the early American church.

In American Catholic Preaching and Piety in the Time of John Carroll, edited by Raymond Kupke, Jesuit Fr. Charles Edwards O'Neill penned an essay titled "John Carroll, the 'Catholic Enlightenment' and Rome," which treats Carroll's views on the relationship with Rome. O'Neill noted that Carroll's visit to Rome from October 1772 to June 1773 left the future bishop "shaken."

Well he might be, because the month after his departure, Pope Clement XIV issued the papal bull Dominus ac Redemptor, suppressing Carroll's order. The Jesuits were no more. Of course, he forevermore resented dealing with the Roman authorities, especially those at the Propaganda Fide, who had long quarreled with the Jesuits and now countenanced this suppression of Rome's most loyal clergy.

O'Neill also places a different reading on Carroll's attitude toward Gallicanism. For example, although he sought and received permission to form a cathedral chapter in 1793, he never did, in large part because that would require investing the clergy with rights, such as not allowing a bishop to remove him from a parish without cause, under canon law that U.S. clergy did not yet have, and that U.S. bishops would prevent them from having throughout the 19th century! (A cathedral chapter is a group of priests who have the right to send the terna for a new bishop, approve major property sales and transfers, etc. The equivalent would be a diocesan college of consultors.)

Ever sensitive to the possibility of anti-Catholic prejudice reemerging, Carroll clearly hoped that future U.S. bishops would be elected by the clergy, as he had been. But when his diocese was erected as a metropolitan see in 1808, with four suffragan sees in Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Bardstown, Kentucky*, neither the U.S. government nor the new archbishop himself protested the fact that the new bishops were not elected.

Instead of any "antipapalism" of the kind Breidenbach describes, O'Neill asserts that Carroll's position "on the choosing of bishops sought no more of Rome than was common for diocesan chapters." And his decision not to form a cathedral chapter shows the degree to which other concerns were paramount in Carroll's mind.

So, then, the question emerges: Does Breidenbach have what he thinks he has? Do we have to adjust our historiography of the role of Catholicism informing, not just benefiting from, the American constitutional experiment in church-state separation? I shall address these questions on Wednesday.

*This article has been edited after publication to correct the number of suffragan sees.