A rainbow is seen at Ste. Marie Madeleine Church in Burgundy, France. Brother Roger Schutz was the founder of the community. (Dreamstime/Farmer)

In the midst of the current political polarization in the United States, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, to say nothing of the day-to-day horror of gun violence in our nation, what a treat to read Volume 1 of the newly translated Journals of Brother Roger of Taizé.

Many know the monastery founded by Brother Roger Schutz as a Protestant center of prayer and work for Christian unity. Others know it for the chants and meditative singing. Still others come from far and wide to the French Burgundian countryside for retreat and renewal. However, Brother Roger's journal gives an insight not only into his hunger for unity but also into some of the struggles he encountered in the process and how he grew open to welcoming Catholics as part of that work for unity.

The physical difficulties of the early years of the monastery give the reader pause. Brother Roger reports that every day, the monks had to walk down from their hilltop village of Taizé to get water for cooking, washing, drinking — every need that the brothers had. Brother Roger noted:

Although we were unprepared for this, we had to do the laundry and take care of all the questions involved in housekeeping, all this for years with no running water. … My conclusion: if I wanted to leave the world, I would go to the city.

This very physical challenge grounds the monastery in its Benedictine spirit of being rooted to the land and the work required to build community. This same Benedictine spirit is the anchor for the welcome offered by the brothers to all who come — even when the work seems daunting.

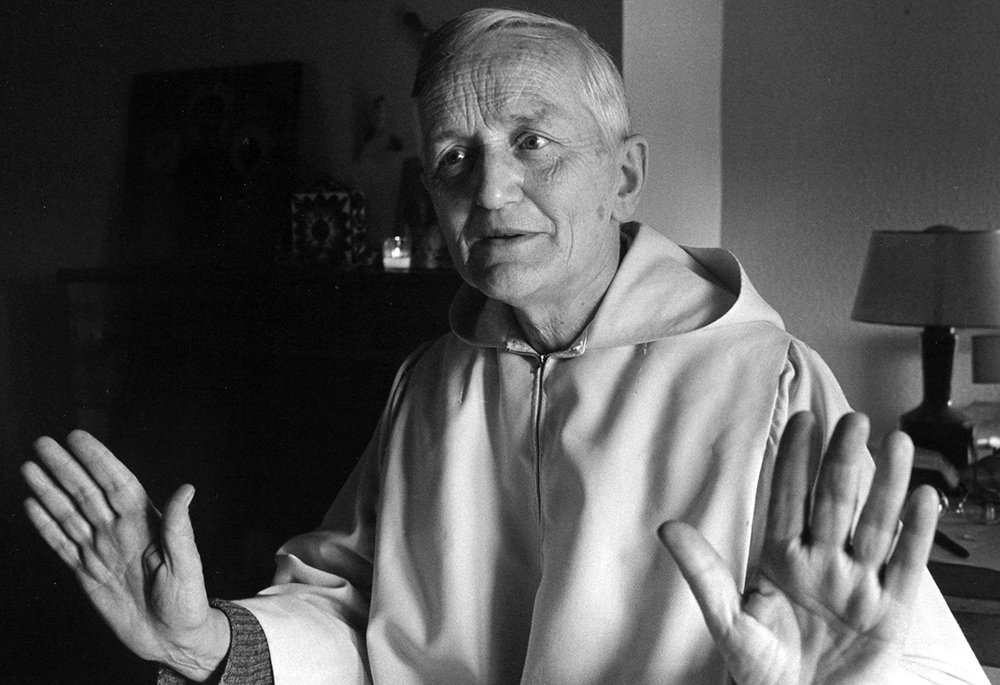

Brother Roger Schutz, one of the 20th century's leading ecumenical figures and the founder of the Taizé community, is seen in this 1982 file photo. (CNS/Reuters)

But, the journal really sets out Brother Roger's hunger for Christian unity and many of the ways that he and the brothers seek to heal the divisions among the various Christian traditions. As a Catholic, I was intrigued to read of Brother Roger's concern about the Catholic Church's insistence of doctrinal certitude. Brother Roger reflects:

I would like to tell Catholics, without causing them any hurt for all that: by living your faith in today's world, at the heart of society you will bridge the gulfs much more than by trying to prove the soundness or the legitimacy of your positions.

However, Brother Roger's engagement with Catholics was extensive, including being an observer at the Second Vatican Council in Rome and meeting with Pope John XXIII, who shared his commitment to Christian unity. But this engagement drew criticism from various Protestant leaders in Europe. Faithful to his vocation, Brother Roger found that forgiveness of the critics was a critical virtue to free him from the "bitterness that poisons and keeps us from loving the flower, the leaf, the dew." It is this forgiveness that was at the center of his work. As I reflected on these words, I thought, could this be a seed to be nourished for healing in our nation?

Advertisement

The prayer of Taizé became the anchor of the forgiveness, love and welcome that radiates out from the ecumenical community. Brother Roger noted:

In any case, everyone gets from it what they can. Our communal prayer is like a mosaic, beautiful for some, shapeless for others. What one person considers meaningless is evocative for another. One appreciates the psalms, or the long silences following the Scripture reading, or the litanies. There are those who especially look forward to the organ music at the end of the service. To each their crumb. To think that everything could be understood with the same intensity, even by just one person, is utopian.

It is this prayer that is the heart of the welcome at Taizé as the brothers focus on youth from all over the world. Being in Taizé, in The Church of Reconciliation for prayer, is an experience of unity. On Sundays, the Eucharist is celebrated by the brothers' ecumenical community and the bread and wine is consecrated/blessed by various faith traditions. This bread and wine is then used during morning Communion services the following week. It is a way of healing division by sharing liturgical practice grounded in meditation on the scripture. It is a shared way forward in Christian unity in a eucharistic practice that is at the heart of the life of the monastery.

This is the level of creative commitment to unity that is needed in our world today. For me, it raises the question: How can we be inclusive of those we disagree with and honor their values and principles as well as our own? Can we find a way forward that does not exclude, but rather welcomes a oneness that we at times only glimpse? This is the challenge of the Gospel in our time.

In this slim first volume of Brother Roger's journals, we find the nourishment to seek unity in our divided world. It is a call to boldness that is desperately needed in these challenging times. Brother Roger quietly urges us to not hold back from engagement for unity. He notes, however that "every courageous step taken involves being criticized." What a small price to pay if we might collectively take a step toward unity in our divided and divisive world.

Brother Roger, lead the way.

This story has been updated to correct the name of the church in the photo caption.