(Dreamstime/Oliver Perez)

"There is no peace because there are no peacemakers."

Jesuit Fr. Daniel Berrigan wrote these words in the early 1970s at the height of the Vietnam War. Not surprisingly, they continue to challenge — and puzzle — many Catholics today. Is he using poetic hyperbole to provoke us? Or is he an overzealous activist that we can simply ignore? After all, billions of believers from all spiritual traditions long for, pray for, walk for and work for peace every day. And during this Easter season, Catholic parishes everywhere were praying for peace in Ukraine at all their liturgies.

Isn't this peacemaking? What is Berrigan trying to tell us? Why does he appear to ignore our Catholic experience, not to mention centuries of what most Christians consider the traditional practice of working for peace?

The answer to this question, I believe, is both simple and complex: simple because we are witnessing a clear reclaiming of Gospel nonviolence; complex because this new vision is disrupting our long-held convictions, as well as creating controversy in our already fractured community.

In his pastoral letter, "Living in the Light of Christ's Peace: A Conversation Toward Disarmament," Santa Fe Archbishop John Wester, speaking from ground zero of the United States nuclear arsenal in New Mexico, describes the "dramatic shift" that is taking place in Catholic teaching on peacemaking. This doctrinal transformation has been emerging slowly but persistently since Pope John XXIII and the Second Vatican Council.

Next year, we will celebrate the 60th anniversary of John XXIII's encyclical Pacem in Terris. Written after the first session of the council and less than two months before his death, this groundbreaking document articulates a renewed understanding of what it means to be a Christian peacemaker.

Gaudium et Spes (1965) and all papal teaching since, culminating in Pope Francis' current prophetic stance, have built on, expanded and deepened John XXIII's vision. At its core, this seismic shift is abandoning the familiar just war theory and reclaiming the message and ministry of the nonviolent Christ.

Advertisement

Obviously, we have only begun to confront this dramatic change, so more choppy seas are likely ahead for the bark of Peter. The just war theory is so deep-seated in our Christian consciousness that it has become the equivalent of a theological given, coursing through our common moral bloodstream. While it is true that some bishops, priests and laity have begun to live into this dramatic shift, for others — perhaps even the majority — this is an unidentified theological object not yet visible on their radar.

What, more exactly, is this given — this millennia-old assumption regarding the just war theory? In simplest terms it reads like this: When we pray for peace or work for peace, it is usually assumed that we mean peace through victory, specifically through military power. The original intent of the just war theory was to limit the destructiveness of war, but over time, it has become the cultural cover for what biblical scholar Walter Wink rightly describes as "redemptive violence."

In other words, it presupposes that military violence is not only necessary but, at times, even a sacred, patriotic duty.

In recent Catholic history, we seem to have forgotten — whether conveniently or not — the prophetic courage of one solitary man. In 1917, as the United States entered World War I, all eligible men were being drafted into military service. Under the leadership of Baltimore Cardinal James Gibbons, the bishops publicly supported and blessed the war, inaugurating the National Catholic War Council, which ironically became the beginning of what is now the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

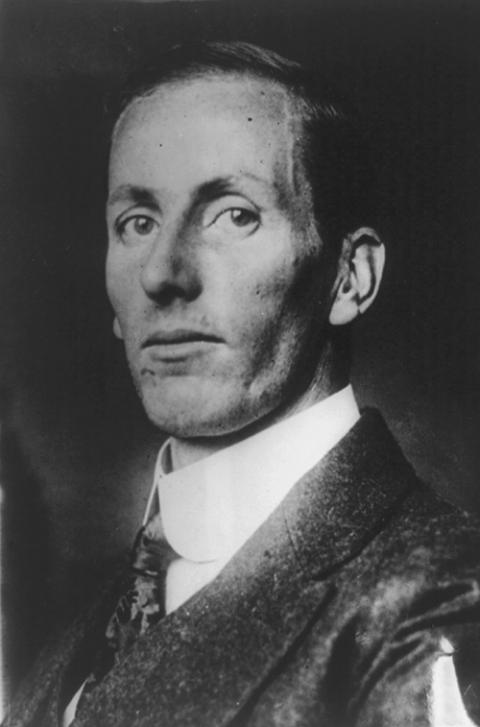

Benjamin Joseph Salmon (1888-1932) was a Catholic layman and an outspoken critic of the just war theory. In 1918, at the age of 29, he refused to fill out the Selective Service questionnaire, leading to his arrest. He was tried in a military court and sentenced to 25 years of hard labor.

Benjamin Salmon, circa 1920 (Library of Congress/National Photo Company Collection)

Imprisoned by the government, condemned by the official church, shunned by his fellow Catholics, he was eventually committed to a mental hospital for the criminally insane. While there, he wrote a 230-page manuscript condemning the just war theory as contradicting the nonviolent Christ. Finally, in 1920, he was released from the hospital and issued a dishonorable discharge from the military service he had never joined.

On his gravestone are engraved the words that shaped his life: "There is no such thing as a just war."

Pope Francis has come to the brink of saying the same thing, and in his pastoral letter, Wester includes a clear affirmation of the nonviolent Christ.

Today, little more than a century later, Salmon's witness exposes the doctrinal earthquake that is rumbling through the church. The most direct evidence of this seismic shift is the growing rupture in our Catholic community, revealing the deep historical fault line between the just war theory and Gospel nonviolence.

How do can we find our way across this chasm? For more than 50 years, courageous people such as Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, Martin Luther King Jr., the Berrigan brothers, the Plowshares movement and organizations such as Pax Christi have been building a bridge of action and dialogue to move our church beyond the just war theory and reconnect us to the nonviolent Christ.

Recently the Gospel Nonviolence Working Group of the Association of United States Catholic Priests has joined this effort. Among other initiatives, it recently published "The Eucharist of Gospel Nonviolence," which has been submitted to the Vatican and the U.S. bishops for their consideration and approval. In further support and in the hope of bringing it to a broader audience, Pax Christi USA, Pax Christi International and the Catholic Nonviolence Initiative have translated it into Spanish and French.

This eucharistic prayer is one step in the long journey toward reclaiming the nonviolent Christ. Still, it has the potential to transform our communal worship and, thereby, our vision and practice of peacemaking. In the early church, the prayer of the community gathered at the eucharistic table served as the creative source of believing and living. In other words, communal prayer creates a shared vision, which, in turn, leads to a transformed way of living. To use the ancient terminology, lex orandi shapes lex credendi, which forms lex vivendi.

What would change if each time we gathered to break the bread of life and share the cup of blessing, we did so in the name of the risen, nonviolent Jesus? Only the Spirit knows the answer to that question. But we can be confident of this: The Eucharist of Gospel Nonviolence will continue to challenge redemptive violence, bring healing to our divisions and call us all to deeper discipleship.