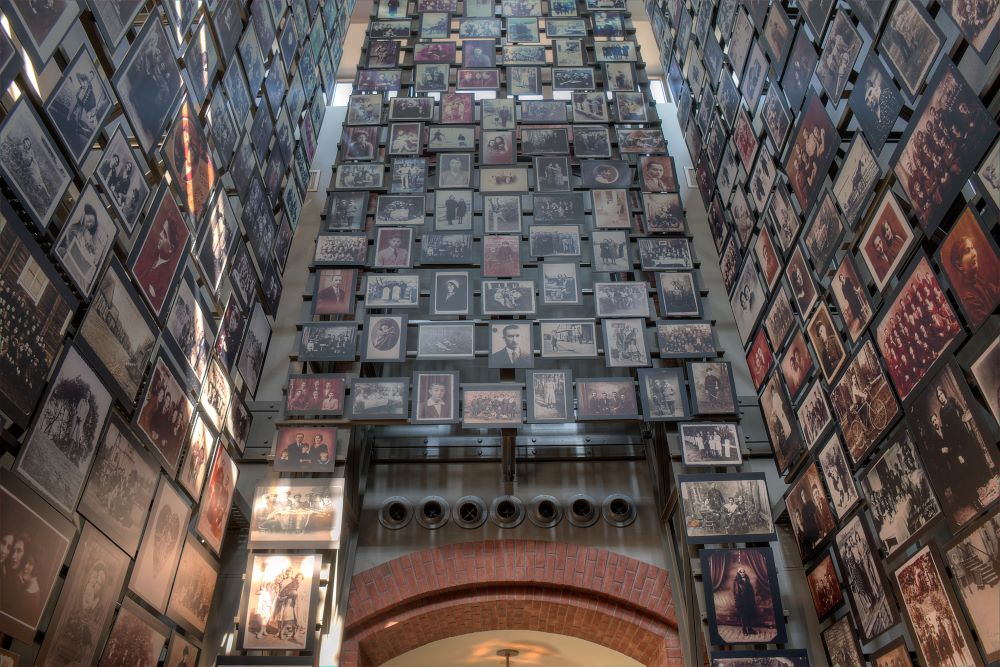

The "Tower of Faces" is a three-story permanent exhibit at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. It highlights the pre-war Jewish community of the Eisiskes, Lithuaniua, where nearly 4,500 Jews were killed during two days of mass shootings on Sept. 25 and 26, 1941. (Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons CC0/Dsdugan)

Journalism and scholarship necessarily require a certain distance from the topic on which they focus. Even here, at NCR, where Catholics write about a church we love and to which we belong, we need to intellectually and imaginatively jump out of our own skin, as it were. We approach our own "I" and our own "we" from outside, as a "me" and an "us."

Studying the Shoah, the murder of 6 million Jews by the Nazis during World War II, is different. There is no way, even at this great distance of time, to approach such an enormous crime, such monstrous human iniquity and suffering, without letting one's own most basic assumptions about life and human dignity be challenged.

Carol Rittner and John Roth have co-edited a new book, The Memory of Goodness: Eva Fleischner and her Contributions to Holocaust Studies, that brings together some of Fleischner's most powerful essays from different periods in her long career as a scholar of the Shoah. At a time when so many of the cultural debates that roil America consist of cheap slogans and manifestos, claims to privileged hermeneutics, and other forms of intellectual and moral sloppiness, this volume demonstrates the moral authority of careful scholarship in all its complexity and power.

After a fine, brief introduction and a chronology of significant events in Fleischner's life, the book divides the essays into three parts: Fleischner's teaching, her writings on those who rescued Jews and related issued of responsibility and, finally, Jewish-Christian relations.

A Russian military doctor examines Holocaust survivors after the liberation of the Nazi death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1945 in Oswiecim, Poland. (CNS/Reuters/Yad Vashem Archives)

Placing the essays on teaching Shoah first was a wise editorial choice, especially the first essay, "A Door That Opened and Never Closed: Teaching the Shoah," in which Fleischner explains how she became interested in the subject and how she confronted the moral concerns that presented themselves the more she learned about the tragic history. It was while pursuing a doctorate in historical theology at Marquette University that two seminars — one on the church fathers and the other on Martin Luther's commentary on the Book of Psalms — turned Fleischner's attention to the subject of Judaism. In both seminars, she encountered Christian anti-Judaism. Then, a friend gave her a copy of Jean-Francois Steiner's 1966 book Treblinka. The door had opened.

Fleischner recounts that when it came time to choose a dissertation topic, she originally thought to write about the meaning of the Shoah for Christians, but a conversation with Rabbi Abraham Heschel convinced her that this was a "dead end." Heschel said, "My dear Eva, there is no meaning to be found in this event." The comment still puts a chill into my heart every time I read it. Fear and trembling indeed.

She recalled that the basic text for her first college course about the Shoah was Raul Hilberg's The Destruction of European Jews, which she selected because of its "excellent historical documentation," even though she and the class "found ourselves reacting negatively to Hilberg's thesis that the Jews contributed to their own destruction through their passivity." Today, I fear, many professors would be afraid to use such a text, but Fleischner explains that "it was precisely this theory, and our anger, that led to some of our best class discussions, making us more aware of the complexity of the issue."

Imagine that? A professor who allows emotions to prompt discussion rather than to shut it down or avoid the controversy altogether?

Lines of barbed-wire fencing enclose the Auschwitz-Birkenau Nazi death camp in Oswiecim, Poland, in this Sept. 4, 2015, file photo. Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany killed 6 million Jews during World War II. (CNS/Nancy Wiechec)

The second essay, "Challenges and Dangers in Teaching the Holocaust," contains a host of really important insights, one of which touches on a point that is also at the heart of the current sense of racial and ethnic accountability in history, such as the Holy Father's planned trip to Canada to apologize for the injustices perpetrated against Indigenous populations. In discussing how she would teach students, many of whom were Christians, about the ways Christianity was complicit in the Shoah, Fleischner writes:

As [the students] try to confront the shadow side of their faith tradition, often for the first time, there is a real danger that they will become overwhelmed by guilt. Quite unjustly in a way, since they personally had nothing to do with the sins of their church. But on the other hand we could say, rightly so, since what is at stake here is a body of Christian teaching which, over many centuries, has denigrated another tradition and human group, often with terrible consequences — a religious tradition which is, moreover, closer to our own than any other.

Those are the words of an educator attentive to the complexity of history and to the pedagogical challenges of teaching subjects that are so fraught.

But it is in the very next paragraph that Fleischner really fine-tunes the critical point. "Guilt which remains guilt is dangerous," she writes. "It will become too heavy a burden sooner or later, and may in the end result in blaming the victim. … We must help our students transform their sense of guilt into a sense of responsibility, for the present and the future."

Mea culpas for the sins of others, especially for historical sins, can be too easy if they do not lead to that sense of responsibility.

Advertisement

One other point Fleischner makes in this essay is worth emphasizing. She writes: "We need to remember that Jewish history is not only, or even primarily, a history of destruction, a vale of tears." One of the most powerful exhibits in the U.S. Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Washington, D.C., is the three-story "Tower of Faces" that contains more than 1,000 photographs of Jews engaged in everyday activities — going on a picnic, celebrating a birthday — in the Lithuanian town of Eisiskes before the war. In September 1941, the Nazis exterminated nearly every Jew in that town. A photo of a pile of corpses is hideous, but it is hard for me to process that. These photos, of the Jews before they became corpses, of people enjoying their lives, they are what breaks one's heart.

The chapter "Teaching of Contempt' is a must-read for anyone trying to understand how antisemitism has functioned through Western history. The next chapter on the importance of Holocaust for Christians is also filled with insights.

The second section of the book deals with the subject of rescuers, those non-Jews who helped save Jews from the catastrophe unfolding around them. Fleischner recounts her reluctance to undertake the project until a Jewish scholar, Yehuda Bauer*, encouraged her to do so. She acknowledges "I had deliberately omitted rescuers from my Holocaust syllabi out of fear that focusing on rescuers would somehow detract from the experience of Holocaust victims."

Still, how important it is to grasp the true evil of the collaborators and the bystanders by learning about those who did not collaborate, those who did not look the other way. She recognizes that the Vatican statement "We Remember: A Reflection on the Shoah" significantly got the adjectives wrong when it observed: "Many [Christians] helped, but some did not."

Few helped. Most did not.

The final section looks at how Jewish-Christian relations have been affected by the Shoah, the spirituality of both Pope Pius XII and Rabbi Heschel, and a deeply personal essay about how Fleischner, the Viennese-born daughter of a Catholic and a Jew, came to a deeper appreciation and love for the Jewish people through her work studying the Shoah.

Fleischner's life, then, was enormously consequential, and her contributions to Holocaust studies profound and enduring. Even in popular culture we say "Never again," but we humans are forgetful persons, and it took years to stop the genocides in Bosnia and Rwanda. Russia's war in Ukraine shows the depths of human depravity in our own time.

Yet the Shoah speaks to us across the decades and we must listen. Fleischner quotes Rabbi Irving Greenberg*: "No statement, theological or otherwise, should be made that would not be credible in the presence of the burning children." That challenge should haunt us and cause us to acquire a sense of responsibility for each other. Eva Fleischner blazed the trail for the rest of us. Blessings upon her memory.

*The spellings of these names have been corrected from the original version.