Centrist candidate and French President Emmanuel Macron, left, and far-right contender Marine Le Pen pose before a televised debate April 20 in La Plaine-Saint-Denis, outside Paris. (Ludovic Marin, Pool via AP)

Sunday's presidential runoff election in France is both strangely modern and old-fashioned, a campaign shaped by pollsters and image-makers, as is the 21st century fashion, but at the same time summoning ghosts that were better known during the Third Republic (1870-1940) than during the current, Fifth Republic (1958-present.) In the middle are Catholic voters who now, in France, seem more and more like Catholic voters in the U.S., voting less as a bloc, their political views trumping their religious values.

"Generally, French Catholic voters support the moderate Right in political matters," Declan Murphy, visiting professor at the EDHEC Business School in Paris told me by email. "But at the moment the traditional moderate right-wing party, Les Républicains, is in a state of dissolution rather like the dissolution of the classical American Republican Party of Eisenhower or Reagan."

Now the options are a neoliberal or a hard-right extremist — the same choice French voters faced five years ago.

In 2017, Marine Le Pen — the daughter of Jean-Marie Le Pen, who founded the far-right National Front — was trounced when she ran against Emmanuel Macron, who started his own, centrist party and captured the presidency with 66.1% to Le Pen's 33.9%. Since her defeat, Le Pen has tried to moderate her image and changed the name of her party to National Rally. Now, after trailing Macron by less than five percentage points in the first round of elections on April 10, she is widely believed to be locked in a close contest with the incumbent.

Her nationalistic rhetoric remains focused mostly on anti-Islamic xenophobia but she has toned down her rhetoric surrounding her signature call to ban the wearing of a hijab in public. Her allies say the ban would be implemented "progressively" and the candidate herself said in a radio interview, "People who are present on our territory, who respect our laws, who respect our values, who have sometimes worked in France, have nothing to fear from the policy I want to pursue."

The anti-immigrant stance of Le Pen has alienated the French bishops' conference. "It is clear that the bishops' conference supports Macron whose policy on the migrants is close to the Vatican statements," said Antoine de Tarlé, a regular contributor to the Jesuit monthly Études and an occasional NCR commentary writer, in an email interview. "The majority of the Catholics who are center right follow that line. There are several far-right Catholic movements who are strongly hostile to Macron but they include only a tiny minority of the population."

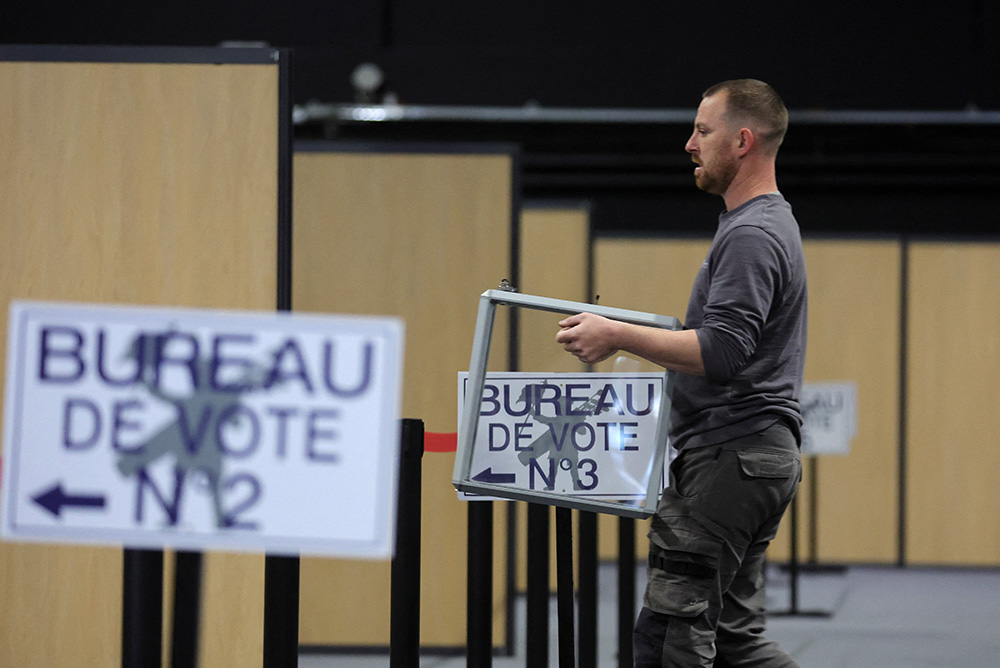

A worker carries a ballot box as he prepares the polling station in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage, France, April 6, for the April 10 presidential election. (CNS/Reuters/Pascal Rossignol)

The war in Ukraine also threw a monkey wrench in the far right's nationalism. Le Pen has been all over the map recently on what kind of policy she would pursue towards Russia, France's ally through much of pre-Soviet history. She has called for a reconciliation with Russia and has pledged to pull France's military out of the NATO command structure, even while minimizing her previously full-throated admiration for Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Le Monde, the afternoon daily in Paris, published a piece reminding voters of the many ties with Putin that Le Pen has been only too happy to trumpet in the past. The newspaper detailed financial links as well as a history of statements of mutual admiration between the two. Now that Putin has graduated from proto-fascist to full-blown fascist, those connections play to people's worst fears about Le Pen.

At America magazine, Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry, a fellow at the conservative Ethics and Public Policy Center, published a strange analysis of the Catholic vote. He wrote:

The appeal of Marine Le Pen for some Catholics, however, runs deeper than opposition to Mr. Macron. Many see French national identity as threatened by the forces of militant Islam and progressivism, and traditional French national identity seems a much more hospitable milieu for Catholicism than either of the alternatives. Sometimes, it seems that Ms. Le Pen is the only candidate who will unapologetically stand up for defending that identity from external threats.

The problem with that paragraph is the repeated use of the word "identity" in the singular, and linking that identity to Catholicism. France may be the "eldest daughter of the church," but like many parent-child relationships, this one is complicated and often fraught.

Historians Anne-Marie and Jean Mauduit entitled their magisterial history of the separation of church and state during the first years of the 20th century "La France contre La France." The two squadrons of dragoons, accompanied by soldiers of the line and some mountain engineers, who descended upon the monastery of the Grand Chartreuse on April 28, 1903, to evict the monks, represented the France of the anti-clerical Prime Minister Émile Combes, the leader of the bloc des Gauches that controlled parliament in those years. His government was united mostly by its desire to close Catholic schools, disband religious orders, and abrogate the Concordat with the Holy See that Napoleon had negotiated with Pope Pius VII. All these goals were accomplished.

Catholics did not vanish with the Concordat and many were understandably hostile to the progressives who had attacked their church. Yet it was France that produced the worker-priest movement immediately after the Second World War. Theological giants like Jean Daniélou, Yves Congar and Henri de Lubac were among the most important intellectual influences on the Second Vatican Council, and Cardinal Achille Liénart was one of the leaders of the reform efforts.

"The Catholic community in France has always had an ambiguous relationship to the Republic and its values," said Murphy. "Because of the persecution of the French Church under the various revolutions, many Catholics refused to support the Republic. Others, like Tocqueville hoped to see a 'liberalization' of Catholicism while still others hoped for a Catholicization of liberalism."

So, when writing of French Catholics, it is wise to refer to their identities in the plural.

Advertisement

Interestingly, the one person who tried to play the Catholic card in this year's election was the candidate who ran to Le Pen's right. "During these elections somebody played the part of using the Catholic identity of France for his antiliberal project," said de Tarlé. "It was Eric Zemmour, a practicing Jew who attends the Synagogue but who delivered opinions closely related to old Action Française." The Action Française was a proto-fascist movement in the early part of the 20th century that wrapped itself in Catholic imagery, but was condemned by Pope Pius XI in 1926.

The strategy didn't work for Zemmour, who only collected 7% of the vote in the first round.

"Zemmour did not understand that the ultra-right Catholics are not interested by old stories concerning the Vichy regime," said de Tarlé. "They are obsessed by very contemporary ethical matters concerning same-sex marriage, abortion and artificial conception."

Le Pen has never been sympathetic to conservative Catholic concerns. "When she took over the party, she got rid of the Catholic extremists who were close to her father," said de Tarlé. "She has refused to fight against abortion and same-sex marriage. Her closest advisers share this position towards the church."

The race is close, although most observers, including Murphy and de Tarlé, think Macron will win reelection. Only if the final tally is very close could any perceived "Catholic vote" prove decisive. Like the U.S., French Catholics no longer constitute a bloc, if they ever did. More determinative will be what happens to those voters who supported the extreme left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who came in a close third in the first round with 22% of the vote to Le Pen's 23.2%.

It is the left, not the Catholics, who will choose the next president of France.