(Pixabay/MonikaP)

Fort Collins, Colorado, was the first place I heard the phrase "outdoor culture." It was, indeed, a beautiful place, in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, with hiking trails, bike paths and fresh waterways within easy access of downtown. "Outdoor culture" didn't describe the physical landscape itself, but rather, the expensive, exclusive world of high-end camping gear, mountain bike shops and high-stakes hiking expeditions that drew tourists and transplants alike to the small western city.

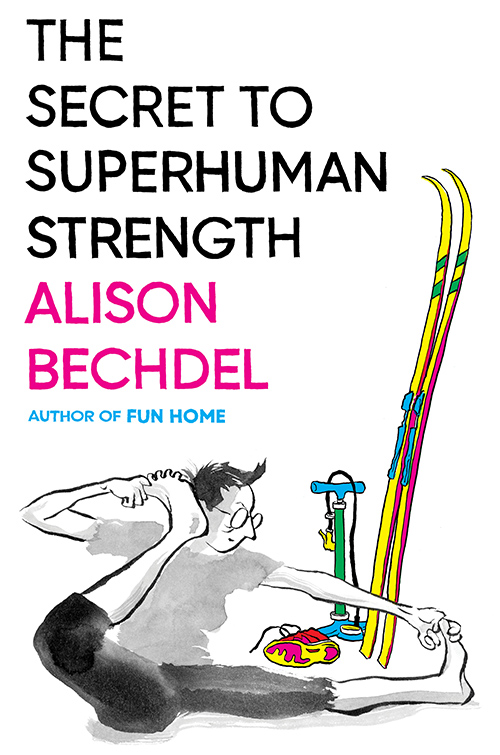

Part literary history, part spiritual journey, part exercise memoir, Alison Bechdel's 2021 graphic novel The Secret to Superhuman Strength explores and historicizes the different metaphysical questions that the godfathers of "outdoor culture" — the Romantics, transcendentalists, and beatniks — have projected onto the American landscape, set alongside her own.

Periodizing her life in decades (as we are encouraged to narrate our time on Earth), Bechdel takes us through the highs and lows of 50 years of fitness crazes, from skiing to yoga to karate to cycling. We follow her through forays into meditation, acupuncture, hallucinogenic mushrooms and her fixation on achieving the elusive, blissful feeling of oneness of body and mind.

The book's refrain — Was this it? The secret to superhuman strength? — lays bare the allure of transcending materialism and mortality through both spirituality and fitness. Rather than reinforce the individualist tropes of "superhuman strength" and material transcendence promised by fitness and spiritual fads alike, Bechdel makes a case for interdependence with other humans as true strength. This theory is forged over 200-plus pages of beautifully illustrated American landscapes, from Appalachia to New England to Minneapolis to northern California.

One of the core strengths of the book is its vulnerability with existential questions. Raised Catholic, Bechdel walks us through her encounters with transcendentalist and Beat Generation writings, both of which were deeply influenced by Hinduism and Buddhism. In the process, we bear witness, with striking visuals, to the difference between exhaustion and calm, focus and anxiety, endorphins and escapism. At the same time, we grapple with the real interconnections between physical, mental, emotional, spiritual and relational health.

(Unsplash/Fitsum Admasu)

Both physical and creative activity emerge in these pages as deeply gendered practices. Bechdel documents the structural sexism that blocked (white, middle-class) women such as Margaret Fuller, a feminist journalist associated with the transcendental movement, from intellectual and creative self-actualization. Bechdel beautifully excavates the women whose childcare, domestic labor and editorial assistance supported celebrated literary figures like Wordsworth, Coleridge, Thoreau and Emerson as they wandered in the wilderness, published and gained notoriety. These women include William Wordsworth's sister Dorothy, Samuel Taylor Coleridge's former wife Sara Fricker, and Ralph Waldo Emerson's second wife Lidian (who penned a satirical "Transcendental Bible," calling out the movement's intellectual elitism).

Bechdel felt this structural sexism and heteropatriarchy in her early ventures into physical activity and the outdoors. There weren't many women's athletic options available in school, which led her to pursue solo games of catch, distance running and skiing. We bear witness as she navigates gender-nonconforming clothing choices (outdoor shops offer the best options) and comes out as a lesbian. Her months of karate training do not adequately prepare her for when a man gropes and then punches her in the New York City subway. And the celebrated men of transcendentalist thought do not offer a way to think about love and struggle, while Adrienne Rich's lesbian feminist poetry does.

These storied life layers position the reader as a fly on the wall for the production of Bechdel's Dykes to Watch Out For, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic, and Are You My Mother?: A Comic Drama, which altogether earned her a 2014 MacArthur "genius" award. The Secret to Superhuman Strength offers an illustrated window into the writing process, and its interconnectedness with every other element of our lives, including our relationship with our bodies. In that sense, the book resonates with other memoirs of the body, such as Kiese Laymon's Heavy: An American Memoir and Roxane Gay's Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body. All three of these texts forge connections between bodily practices and avoidance of trauma/grief; in Bechdel's case, her grief over her father's suicide.

Unlike Gay's and Laymon's texts, however, racism, sexual violence and intergenerational trauma are not constitutive of Bechdel's body narrative.

For example, Bechdel's flashbacks to earlier canonical literary figures, combined with her foray into backcountry sports, demand a reckoning with the privilege of free mobility. As she writes, transcendentalist philosophies responded to the racism and exploitation of the time ("slavery, the 'Indian Removal Act,' grabbing land from Mexico, the subjection of women, [and] brutal conditions in the new factories"), but she locates the transcendentalist philosophy's answer to this context is primarily (if not totally) in "inner transformation."

The relationship of humans to land, in this framework, is largely about recreation; nature exists primarily as a tableau for romantic relationships, physical exertion, spiritual purification and writers' interior lives. I would love to see Bechdel explore her relationship to land as central to not only the mind/body relationship, but also to her theory of interdependence.

Advertisement

Interdependence looks different when it is premised on an understanding of the U.S. landscape as a colonized space with longstanding history, memory and trauma woven into every encounter with it. Human/land hierarchies are centrally constitutive of colonization, and by understanding this, we can expand our notions of interdependence beyond the realm of only humans (and the occasional cat). Works like Lauret Savoy's Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape focus more squarely on the deeply historical, spiritual and contested relationship between humans and land. Bechdel, in contrast, situates her metaphysical journey as exploring the "relationship between humans and the universe," becoming part of a long line of Euro-descended writers in the U.S. who came before her.

This understanding of interdependence is not unique to Bechdel. After leaving Fort Collins to move back to New York, I jokingly described Colorado's "outdoor culture" to a Palestinian friend, but admitted that I loved to camp. She waved off camping as "American settler colonial fantasy." Whether or not we are white, we can still be indoctrinated into a white-settler relationship to land. And whether or not we are white, we can still be seduced into spiritual bypassing, which obscures systemic failures (to quote my mental health counselor sister).

Bechdel's text offers a window into one writer's struggle with existential questions, and the role of the people and landscapes around her in shaping her answers.