(Unsplash/Christina@wocintechchat.com)

Since Moya Bailey coined the term "misogynoir" supporters and critics alike have thrust the term into the limelight.

The term, which Bailey first created in 2008 but used publicly in 2010, is a combination of NOIR — the French word for black — and misogyny, and refers to "the uniquely co-constitutive racialized and sexist violence that befalls Black women as a result of their simultaneous and interlocking oppression at the intersection of racial and gender marginalization."

Bailey, an activist, writer and professor at Northeastern University, created the term to pinpoint the specific, various ways Black women are disregarded and dehumanized worldwide. Sexuality, gender and race have been the backbone of her research and writing, which examines how popular culture and media perpetuate the mistreatment of Black women.

In 2010, Bailey used "misogynoir" outside her dissertation for the first time publicly in "They Aren't Talking About Me …," an essay for Crunk Feminist Collective. Following the essay's publication, other Black feminist thinkers, including writer and social critic Trudy, adopted the term into their work and helped Bailey's work go viral.

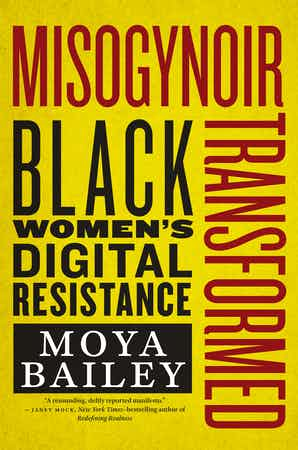

Her first book, #HashtagActivism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice, co-authored with Brooke Foucault Welles and Sarah J. Jackson and published in 2020, focused on Twitter's significance for marginalized groups like Black women and transgender women and men. Her latest book, Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women's Digital Resistance, published earlier this year, focuses on how and why misogynoir serves as a critical framework for people writing, thinking and organizing more deeply around Black women's systemic plights.

Misogynoir Transformed centers Black women and nonbinary, agender and gender-variant people and introduces readers to two new terms: defensive digital alchemy and generative digital alchemy. Digital alchemy refers to the ways in which marginalized groups "transform everyday digital media into valuable social justice media that recode the failed scripts that negatively impact their lives." Bailey states that "defensive digital alchemy takes the form of responding and recalibrating against misogynoir, while generative digital alchemy moves independently, innovated because it speaks to a desire or want for new types of representation."

Defensive digital alchemy occurs when these groups use whatever digital tools they have available, like hashtag campaigns on Twitter or Facebook, to fight misogynoir. "It typically takes the form of a one-to-one response — for example, #RuinABlackGirlsMonday is met with #RuinAnInsecureBlackMansTuesday," Bailey writes. Generative digital alchemy, on the other hand, "is not concerned with responding directly to the misogynoir that might inspire its production."

Advertisement

Bailey's entire book is an act of generative digital alchemy.

Through an intentional approach of telling the oppressed groups' narrative, Bailey eliminates the white gaze to exclusively engage and focus on Black, queer feminist theory as a way to provide healing for misogynoir's survivors rather than amplifying afflicted abuse.

Bailey uses a mixed-media approach, compiling examples of misogynoir from Twitter archives, YouTube videos, crowdfunded web shows created by and about queer Black women and popular television shows. She highlights tropes illustrated by performances including comedian Billy Sorrell dressing in drag for the viral 2011 YouTube video "Sh*t Black Girls Say"; Shenehneh, played by Martin Lawrence on the 1990s titular comedy show; and BlameItOnKWay's TiTi character, an insecure, loud, dark-skinned girl sporting an aqua green lace front and neon pink lipstick. BlameItOnKWay's character was so popular that Tyler Perry, who has also built a billion-dollar empire on the back of his gun-slinging, violent caricature of Madea, invited him on his final Madea play tour.

Bailey naming these characters is not dogpiling nor some shot in the dark — it's reflecting how often popular culture relies on misogynoiristic depictions of Black women.

Misogynoir Transformed illustrates how, despite the prevalence of misgoynoir in everything from movies to social media, Black nonbinary, agender and gender-variant folks have created ways to participate in generative digital alchemy.

The trans community shared tactics against transmisogynoir, for example, in demands to fight for CeCe McDonald, a trans Black woman who was sentenced to 41 months in prison for defending herself against a violent transphobic neo-Nazis outside a Minnesota bar, killing one of them. (Here is misogynoir again, metastasizing in judicial practices.) The hashtag #FreeCeCe was created to challenge the sentence, later reduced to 19 months.

We also see digital resistance with the April 2012 #FreeCeCe petition that reached almost 20,000 signatures in one month with the help of Janet Mock, a trans woman, activist and actress. McDonald, while incarcerated, also ran an online blog, "SupportCece.com," which helped amplify messages directly from her.

Using digital tools such as Gephi and Voyant to analyze text, Bailey provides examples of how people describe and comment on the bodies of Black girls versus white girls, particularly in instances where Black girls are targeted by law enforcement. She cites the 2015 McKinney, Texas, incident in which Dajerria Becton, a 15-year-old Black girl, was slammed to the ground and dragged by a white police officer named Eric Casebolt. The disturbing seven-minute video was filmed and uploaded by a white boy named Brandon Brooks. The video reached more than 10 million views and garnered countless comments, including but not limited to viewers who blamed Becton for the assault. This demonstrates how misogynoir violently impacts Black girls, Bailey points out.

The book also focuses on social networks that came before Instagram and Twitter, and describes how sites like Tumblr created a blueprint for building communal and political spaces online.

Bailey’s personal experiences with Tumblr’s "heyday" (described as 2009-2015) is fitting. For Bailey, a Black, queer woman, misogynoir is a personal, communal battle. Tumblr provided her access to the ethnographies of queer and trans people of color and allowed her to create generative digital alchemy before it existed. Tumblr relationships also turned into communal, physical spaces in conferences like the annual Allied Media Conference.

As misogynoir continues to evolve, digital users are creating new avenues to fight the ways that it continues to go unchecked, online and in real, everyday interactions. Misogynoir Transformed is gut-wrenching to digest, but Bailey’s retelling of the ugly impact of misogynoir on everyday life is a mandatory swallow.

Bailey's digital research creates a succinct timeline of the existence of misogynoir in U.S. culture even before she coined the term.

Between love letters to Tumblr and excellent, nuanced research, Bailey demonstrates Black women's evolving battle against misogynoir and how the fight for their humanity continues on digital platforms that were never meant to protect them.